A. S. King’s unforgettable novel Please Ignore Vera Dietz is out through Text this month. John Green has described A. S. King as ‘one of the best YA writers working today.’

True.

But we at Text happen to know that quite a few other people would venture to say that she’s the best YA writer working today.

We asked one of those people – the effervescent Danielle Binks, of the LoveOZYA Anthology book fame, of Kill Your Darlings fame, of the Alpha Reader book blog brilliance, as well as of literary agent wondrousness – if she’d like to ask A. S. King a couple of questions that she didn’t get to ask when they spoke together in Australia last year.

She agreed. We were thrilled. The below is the result. Read and enjoy – then stick around for a writers’ flowchart from A. S. King, as well as an extract from Please Ignore Vera Dietz.

Take it away, Danielle!

I work in youth literature. It’s pretty much my whole life. I write, advocate, edit, review, and even sell it as a literary agent.

I have bountiful thankfulness for the books I read growing up that ensured I’d always live for this readership, plus a deep respect and fascination with modern young-adult (YA) literature.

But if you ask me who the one author is that’s writing YA today, who I wish with every fibre of my being had existed when I was a teen, I have only one answer.

A. S. King.

Her books are not easy. Her books are not ‘nice’. But I know that she is one of the most important voices writing in YA fiction today for the very reason that she’s constantly testing boundaries and pushing readers out of comfort zones.

Because A. S. King writes without limit. And I could have done with some of that, when I was growing up.

Last year I had the thrill of my life getting to meet this author whom I have idolised since first reading her way back in 2011. I got to witness the impact and affect she had on teenagers when she joined the Centre for Youth Literature’s Reading Matters Conference line-up. The way A. S. King spoke to auditoriums full of teens – with steely-eyed honesty and deep-seated respect that only comes from truly knowing what it is to be young and hurting – that’s exactly the way she writes for them too. And they are so floored and shocked by her audacious authenticity – an adult who actually treats them and their pain as real and profound. It was an honour to witness the impact she had on each and every young person who was lucky enough to hear and read her words.

Which is why I am so excited that even more Aussie teens will get that chance, now that Please Ignore Vera Dietz has landed in Australia. It remains my favourite of hers. A novel of sheer magnificence, about heartbreakingly flawed and complex young characters – with no pulled punches, just deep understanding for the absurdity and beauty of life. It’s about bullying and grief, abandonment and ignoring a problem until it festers and explodes. But above all else, it’s a novel of forgiveness. Forgiving other people and ourselves – the mistakes and bad choices, the pain inflicted and emptiness left behind.

This book is a gift, and even if I wasn’t lucky enough to have A. S. King growing up, I am so thankful and relieved that today’s teens do.

And that’s enough. Hell, it might even be everything.

What were you like as a teen? And what were some of the formative works you encountered that still shape your writing today?

The farther I get from my teen years, the more I see myself as a fairly confident teen, even though I was a walking contradiction. For example: I was a determined athlete and a fantastic cigarette smoker. Also: I was determined to do something that would somehow help the world, and yet the prescribed path to this – school – was something I loathed.

But reading? And thinking? And writing? That was for me.

Funny that I separate these things from school but…now more than ever in American education, administrations are forcing teachers to teach to a test so maybe I was ahead of my time in opting out.

I read a lot as a kid, and once I got into my teens, I was required to read Paul Zindel’s The Pigman. I fell for Zindel. I read everything he’d ever written many, many times. I’d say the most important book for me as a teen and as a writer early on was Confessions of a Teenage Baboon. Zindel crafted well-defined and very strong adult characters and told stories of teens navigating adults. For me, that’s the definition of being a teen. Navigating adults.

When I first entered the YA world here in the US, I had more than one editor reject my work because it contained fully-formed adult characters. I stuck with what felt true to me because that’s what artists have to do.

Why do you write YA?

I believe teenagers are capable, complex human beings, and I love writing for them and about them. I didn’t do this on purpose. I’d been writing novels for a long time and at some point (far later than I should have) I realised that all of my characters’ stories started in their teen years. I wondered why. I came to this conclusion: our early years are called formative for a reason. Everything that happens to us before the age of ‘adulthood’ forms us. What an exciting, expansive time of life to study – the formative years. And what a fantastic way to help the world – to write honest portrayals of these formative years so teenagers could see themselves in books, face hard things and grow into stable adults. So, that’s my hindsight answer. But really, there was no why. I just naturally wrote this way.

What is it about teenagers that makes you want to write for – and about – them?

I’m really, so, utterly tired of seeing teenagers get a bad rap. They are the punchline to so many jokes. For what? Having an age that starts with the number one? When a toddler trips over their own feet, we ask them if they’re okay. Add ten years and if the same kid trips over their own feet, we snap at them or make them the brunt of a joke. I meet a lot of teenagers in a year and when I ask them, ‘Hey – have you guys noticed that adults roll their eyes at you a lot?’ they all say yes.

This upsets me because teen years are some of the hardest to get through and it’s hard enough without the added eye-roll. It also upsets me because all of us were teenagers once and I can’t quite figure out where this superiority comes from. I see it in twenty-somethings and beyond – as if the minute we are no longer teens, we are out to be better than the people still stuck there. I don’t know. I’m passionate about how smart and caring teenagers are. I’m amazed by how open-minded they are. I don’t understand why they are, in most cultures, the butt of our jokes.

And on a serious note…we are living in an age where teenage mental illness is an epidemic. I reckon it’s about time we STOP calling teenage emotions DRAMA. Stop it. Now. It’s time to take things seriously. I’ve had people argue with me on that – they say that teenage emotions are fleeting, they are happy one minute and sad the next. Yeah. Maybe. But will being an asshole about it help them in any way? No. So stop.

And what do you say to any critics who throw out the tired question ‘Will you ever write a “real” book – for adults?’

Oh, please. I’ve heard this a few times – always from someone who hasn’t read my books or who doesn’t read young-adult books or any books at all. Anyone saying that sort of garbage is just out to make another person feel small. Which, to me, makes the asker seem small. Seriously. I’m probably too busy writing an awesome book to answer this question in real life.

Why do you think parent characters often get forgotten in a lot of modern YA? You make a point of writing multifaceted adults in your teen characters’ lives – like the wonderful father Ken Dietz in Please Ignore Vera Dietz.

I will admit to not really liking books where teens or children are the only people populating the landscape. It seems so unrealistic to me.

I will tell you what happened to Ken Dietz in Please Ignore Vera Dietz when editors were reading it and bidding on it. He nearly got cut from the book. It started with me asking one editor if she had any editorial ideas and she said, ‘We have to cut the father, of course.’ I was like, ‘Whoa, wait, what?’ Then I asked about Ken’s flowcharts. She said ‘Yeah, those go, too.’ I asked why. Her answer was: TEENS ONLY WANT TO READ ABOUT TEENS.

Still breathing?

Good.

So, I don’t agree with that. Especially considering my earliest inspiration was Confessions of a Teenage Baboon by Zindel. I LOVED reading about adults.

So, if I was to guess, the answer to the WHY of this question is: for some weird reason, there are editors and other publishing or even library professionals who have a problem with adults in YA or children’s books. Often, you will hear the agency reasoning, which goes like this: make sure there are no adults in the book solving problems because the whole point of a book for children and teens is that they have to solve all the problems themselves!

And we wonder why kids don’t come to adults for help.

I may be weird for thinking that way but I’m still reeling, ten years later, at the original misconception that teens only want to read about teens. As if all teens were just cranked out of the teen factory identical to every other teen.

I should add that my goal since I dreamed of being a writer at age fourteen was to write books that help adults understand teens better and to help teens understand adults better. So for me, there was never a question of including both age groups. My 2019 book is three generations wide. I’ve always been fascinated with generational differences, and how we navigate them as humans.

Your books are weird and wonderful, and like they’re sometimes showing the real-world through a fun-house mirror, slightly off-kilter… What do you say to those who ask if the surreal and bizarre in your books are ‘real’ or figments of your characters’ imaginations? For instance – is the pagoda really sentient in Vera Dietz?

Oh, that pagoda. Hmm. Well, I guess life is surreal, Danielle. I mean, it is, right? And who better to write about in that sense than teenagers? Teen years – talk about surreal. So I think literary elements like sentient pagodas make sense in all books, but especially YA books, I guess, because teens live lives full of surreal expectations. Do this, do that, don’t forget this, make sure you do that, get a job, do your homework, and WHY AREN’T YOU RELAXED/HAPPY/SMILING?

See what I mean?

In the case of the pagoda, that book wrote itself and when the pagoda started talking, I had to listen. It said some smart stuff. And it had the widest view of the town, the characters, and it knew the truth. The real truth – all of it. Which is more than the characters populating the book had.

But what do I say to people who want linear answers? I say: you may have read the book too quickly. See if you can read it next time like it’s a painting or your favorite band’s album.

What do you want to say to those who think that the real world is bad enough, so teens should only read ‘happy’ YA books that offer them a reprieve from fear and pain, instead of tackling it head on as you do?

I don’t even know what to say. I mean, children’s television is there if anyone wants to go back to watching Elmo, I suppose. But seriously. What part of life isn’t contradictory inside of every second? What part of our lives is just picture perfect for every minute? Um, none. If adults want to argue that their kids have everything they need, yeah, so do mine…but they also have pain and all kinds of things that make them sad. If no one talks about it, then they feel like freaks for this. And then they hold it all in. And then what? Look around. What happens when kids hold everything in to make their parents happy and meet social expectations? A lot of bad shit. That’s what happens.

Her are some numbers. One in four American teenagers are suffering from mental illness. Seventy per cent go untreated. One in four women are sexually assaulted before they graduate college. One in four girls and one in seven boys have experienced childhood sexual abuse. Forty-five per cent of children have lived through the divorce of their parents. This is the tip of the shitty iceberg that is life. For all of us. Denying teenagers a helpful and real outlet for their pain is cruel. Deciding not to educate teens who don’t fit into any of these categories is cruel, too, because life is on the way and bad shit happens to people they know, their spouses, their children.

On a more serious note (hold on…more serious than that?). In America, a kid could get shot and die while they sit in chemistry class because we have gun violence that is the most surreal and unimaginable thing I have ever witnessed. You want me to make my books HAPPY? How’s that going to help their trauma? All kids by the time they hit high school have trauma. We blow it off as drama. They watch kids all over this country get gunned down in school. Even if they aren’t in that school, that’s trauma. National trauma. Yesterday seventeen people died in a school shooting. Today, we are numb – I feel like I am living inside a zombie’s body. This is trauma.

So yeah. Come at me. I’ve got a pocketful of stats for anyone who feels teenagers should be sheltered. Also, to anyone who thinks teenagers shouldn’t read curse words, I have a pocketful of those, too.

What is the number one piece of advice you’d give your teen self? (And is this the inspiration behind all your novels?)

I have never been asked this question before in this way and I love you for it. Because I sat here thinking about it at first, and I think if I was able to go back in time and tell myself not to worry so much about all the crap people told me was important, I’d have been a lot more relaxed and happy. In more blunt terms: keeping up with the Joneses is complete bullshit.

And yes, I’m pretty sure that’s the message inside all of my novels. Among other things. I never knew that before. Thanks.

When are you coming back to Australia?

I thought I’d be back this year, but it turns out I’m heading to New Zealand for their smashing Auckland Writer’s Festival in May. I’m sad I can’t make it to your shores this time around. You know how much I loved being there last year. Australians are of my sensibility. That weird Ireland/American mix. (And you pronounce yogurt the same way as we do, which is how the world should be.)

Did your time here last year bring up any inspiration for you?

I am now eight months from my time in Australia and there’s one thing that keeps coming back to me when I talk about it.

My time in Melbourne was particularly eye-opening in that it is a globally diverse city. I’ve been to a lot of major cities. Nothing comes close to the feeling of welcome global diversity there for me. I don’t know how else to describe it.

When the conference opened, Adele thanked the indigenous tribe on whose land the conference was being hosted. This was the coolest thing I ever saw. You must understand, I am from America where this may happen in some places, but I’ve never seen it and I’ve been around. So I’ve always been an American who craves diversity and difference, and who has always wanted to talk openly about the crimes that occurred in my country – the crimes that enabled my country to be a country/the crimes that this country was founded on. I want us to finally respect the people who survived our genocide. I’d like a lot more, but the first step is respect and acknowledging the truth of our history.

Native American history isn’t taught outside of inaccurate and dismissive accounts of what really happened. And slavery is so inaccurately taught, proportionally distorted, still not being openly discussed in order to understand present day reality. Those are both understatements. I can’t really dive into how much work we have to do on those fronts or count how many other fronts we should be working on here. The list is enormous. But to see that simple gesture – thanking for the use of the land. That acknowledgement of true history. It made me cry on the spot. I wish we did that here. I wish we had the sensibility to talk openly about anything without an argument arising. So far, that’s not happening over here. So Australia was pure inspiration. Full marks for being awesome.

How do you think Aussie teens are different from American ones?

From what I saw when I was there, Australian teens really understood my more Irish side – meaning the side of me that talks about communities and volunteering and being part of making things in your country/area better. They weren’t afraid to talk about mental health and they didn’t balk when I talked about it, nor non-consumerism or my years being self-sufficient. They seemed to totally understand why I talked about race and how important it is to know the privilege of whiteness. I felt less weird in Australia, generally.

Now, that’s not to give American teens a bad rap. American teens are plenty savvy and smart and capable and empathetic. However, they are often shocked when I speak so openly about mental health, race, or the personal responsibility we have to our communities. Some are either so used to being universally dismissed and devalued, or they are just not used to adults talking to them about personal things so openly? I don’t know. I do feel weird here but that’s because I lived so long abroad and I think I can be weird-seeming to people who don’t know many women who speak passionately about certain topics.

I felt a confidence among Aussie teens that came from something deeper in their education, an openness to learning – something that gave them credit for being almost to adulthood. A sense of belonging and maturity. I’m sad to say that I don’t see that as often here. (I DO see it, but not as often, that’s all.) American high school has become a series of standardized tests and rites of passage floating on the surface of a great education offered by great educators…who are often at the mercy of an administration that is distracted by what floats on the surface. Confident maturity – while juggling a natural rebellion against a culture that is constantly belittling them – is all over the place, but that belittling takes its toll on that confidence.

Here’s a line from Please Ignore Vera Dietz that sums up how I feel about living in America, what it’s like for teenagers to live in America, and that sums up this entire interview!

‘I’m sorry, but I don’t get it. If we’re supposed to ignore everything that’s wrong with our lives, then I can’t see how we'll ever make things right.’

All of the above and every word in Please Ignore Vera Dietz are just some of the reasons why Text is in love with A. S. King.

But wait – there’s more!

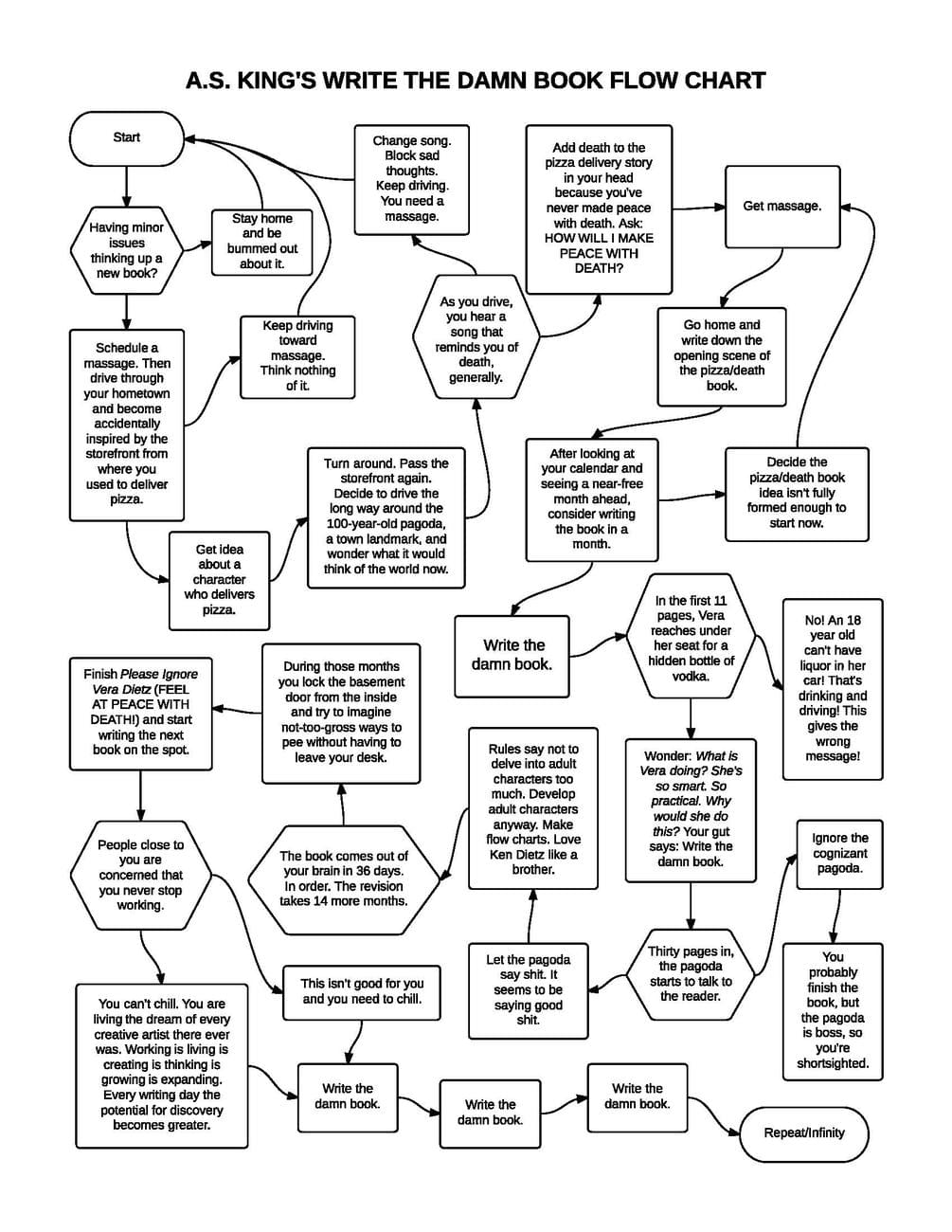

While we were recently chatting with A. S. King about her books, she sent us a flowchart, in the spirit of Mr Ken Dietz, that she put together to get her motivated in the middle of writing slumps. She also said we could share it with you.

Are we all clear now? This is how you sort your writing life OUT.

And now an extract from Please Ignore Vera Dietz by A. S. King.

Vera’s spent her whole life secretly in love with her best friend, Charlie Kahn. And over the years she’s kept a lot of his secrets. Even after he betrayed her. Even after he ruined everything. So when Charlie dies in dark circumstances, Vera knows a lot more than anyone – the kids at school, his family, even the police. But will she emerge to clear his name? Does she even want to?

Edgy and gripping, Please Ignore Vera Dietz is an unforgettable novel: smart, funny, dramatic and always surprising.

PART ONE

THE FUNERAL

The pastor is saying something about how Charlie was a free spirit. He was and he wasn’t. He was free because on the inside he was tied up in knots. He lived hard because inside he was dying. Charlie made inner conflict look delicious.

The pastor is saying something about Charlie’s vivacious and intense personality. I picture Charlie inside the white coffin, McDonald’s napkin in one hand, felt-tipped pen in the other, scribbling, “Tell that guy to kiss my white vivacious ass. He never met me.” I picture him crumpling the note and eating it. I picture him reaching for his Zippo lighter and setting it alight, right there in the box. I see the congregation, teary-eyed, suddenly distracted by the rising smoke seeping through the seams.

Is it okay to hate a dead kid? Even if I loved him once? Even if he was my best friend? Is it okay to hate him for being dead?

• • •

Dad doesn’t want me to see the burying part, but I make him walk to the cemetery with me, and he holds my hand for the first time since I was twelve. The pastor says something about how we return to the earth the way we came from the earth and I feel the grass under my feet grab my ankles and pull me down. I picture Charlie in his coffin, nodding, certain that the Great Hunter meant for everything to unfold as it has. I picture him laughing in there as the winch lowers him into the hole. I hear him saying, “Hey, Veer – it’s not every day you get lowered into a hole by a guy with a wart on his nose, right?” I look at the guy manning the winch. I look at the grass gripping my feet. I hear a handful of dirt hit the hollow-sounding coffin, and I bury my face in Dad’s side and cry quietly. I still can’t really believe Charlie is dead.

The reception is divided into four factions. First, you have Charlie’s family. Mr. and Mrs. Kahn and their parents (Charlie’s grandparents), and Charlie’s aunts and uncles and seven cousins. Old friends of the family and close neighbors are included here, too, so that’s where Dad and I end up. Dad, still awkward at social events without Mom, asks me forty-seven times between the church and the banquet hall if I’m okay. But really, he’s worse off than I am. Especially when talking to the Kahns. They know we know their secrets because we live next door. And they know we know they know.

“I’m so sorry,” Dad says.

“Thanks, Ken,” Mrs. Kahn answers. It’s hot outside – first day of September – and Mrs. Kahn is wearing long sleeves.

They both look at me and I open my mouth to say something, but nothing comes out. I am so mixed up about what I should be feeling, I throw myself into Mrs. Kahn’s arms and sob for a few seconds. Then I compose myself and wipe my wet cheeks with the back of my hands. Dad gives me a tissue from his blazer pocket.

“Sorry,” I say.

“It’s fine, Vera. You were his best friend. This must be awful hard on you,” Mrs. Kahn says.

She has no idea how hard. I haven’t been Charlie’s best friend since April, when he totally screwed me over and started hanging out full-time with Jenny Flick and the Detentionhead losers. Let me tell you – if you think your best friend dying is a bitch, try your best friend dying after he screws you over. It’s a bitch like no other.

To the right of the family corner, there’s the community corner. A mix of neighbors, teachers, and kids that had a study hall or two with him. A few kids from his fifth-grade Little League baseball team. Our childhood babysitter, who Charlie had an endless crush on, is here with her new husband.

Beyond the community corner is the official-people area. Everyone there is in a black suit of some sort. The pastor is talking with the school principal, Charlie’s family doctor, and two guys I never saw before. After the initial reception stuff is over, one of the pastor’s helpers asks Mrs. Kahn if she needs anything. Mr. Kahn steps in and answers for her, sternly, and the helper then informs people that the buffet is open. It’s a slow process, but eventually, people find their way to the food.

“You want anything?” Dad asks.

I shake my head.

“You sure?”

I nod yes. He gets a plate and slops on some salad and cottage cheese.

Across the room is the Detentionhead crowd – Charlie’s new best friends. They stay close to the door and go out in groups to smoke. The stoop is littered with butts, even though there’s one of those hourglass-shaped smokeless ashtrays there. For a while they were blocking the door, until the banquet hall manager asked them to move. So they did, and now they’re circled around Jenny Flick as if she’s Charlie’s hopeless widow rather than the reason he’s dead.

An hour later, Dad and I are driving home and he asks, “Do you know anything about what happened Sunday night?”

“Nope.” A lie. I do.

“Because if you do, you need to say something.”

“Yeah. I would if I did, but I don’t.” A lie. I do. I wouldn’t if I could. I haven’t. I won’t. I can’t yet.

I take a shower when I get home because I can’t think of anything else to do. I put on my pajamas, even though it’s only seven-thirty, and I sit down in the den with Dad, who is reading the newspaper. But I can’t sit still, so I walk to the kitchen and slide the glass door open and close it behind me once I’m on the deck. There are a bunch of catbirds in the yard, squawking the way they do at dusk. I look into the woods, toward Charlie’s house, and walk back inside again.

“You going to be okay with school tomorrow?” Dad asks.

“No,” I say. “But I guess it’s the best thing to do, you know?”

“Probably true,” he says. But he wasn’t there last Monday, in the parking lot, when Jenny and the Detentionheads, all dressed in black, gathered around her car and smoked. He wasn’t there when she wailed. She wailed so loud, I hated her more than I already hated her. Charlie’s own mother wasn’t wailing that much.

“Yeah. It’s the first week. It’s all review anyway.”

“You know, you could pick up a few more hours at work. That would probably keep your mind off things.”

I think the number one thing to remember about my dad is that no matter the ailment, he will suggest working as a possible cure.

THREE AND A HALF MONTHS LATER – A THURSDAY IN DECEMBER

I turned eighteen in October and I went from pizza maker to pizza deliverer. I also went from twenty hours a week to forty, on top of my schoolwork. Though the only classes worth studying for are Modern Social Thought and Vocabulary. MST is easy homework – every day we discuss a different newspaper article. Vocab is ten words a week (with bonus points for additional words students find in their everyday reading), using each in a sentence.

Here’s me using parsimonious in a sentence.

My parsimonious father doesn’t understand that a senior in high school shouldn’t have a full-time job. He doesn’t listen when I explain that working as a pizza delivery girl from four until midnight every school night isn’t very good for my grades. Instead, my parsimonious father launches into a ten-minute-long lecture about how working for a living is hard and kids today don’t get it because they’re given allowances they don’t earn.

Seemingly, this is character-building.

Apparently, most kids would be thankful.

Allegedly, I’m the only kid in my school who isn’t “spoiled by our culture of entitlement.”

This was supposed to keep my mind off Charlie dying – which hasn’t worked so far. It’s only made it worse. The more I work, the more he follows me. The more he follows me, the more he nags me to clear his name. The more he nags me, the more I hate him for leaving me with this mess. Or for leaving me, period.

I’m at the traffic light outside school and I slip the red Pagoda Pizza shirt over my head. I don’t care if it messes up my hair, because I need to look a mix of crazy, disheveled, and apathetic to maintain the balancing act of getting good tips and not getting robbed. I reach under my seat and feel around for the cold glass, and when I find it, I slide it between my legs and twist the metal cap off. Two gulps of vodka later, my eyes are watering and my throat automatically grumbles “Ahhhhh” to get rid of the burning. Don’t judge. I’m not getting drunk. I’m coping.

I pop three pieces of Winterfresh gum into my mouth, slip the bottle back under my seat, and turn left into the Pagoda Pizza delivery parking lot.

My boss at Pagoda is a really cool biker lady with crooked yellow teeth, named Marie. We have two other managers. Nathan (Nate) is a six-foot-five black guy with square 1980s glasses, and Steve is in his forties, drives a Porsche, and lives with his mom. One of the other drivers told me that he’s loaded and he only works here for fun, but I don’t believe what the other drivers say. Most of the time, they’re stoned. They tell me, when we’re mopping the floor or washing the dishes after closing, that when they’re high, they can’t look at Marie because her teeth freak them out.

Marie is running the store tonight, and when I get in, she smiles at me, like a bagful of broken, sun-aged piano keys, and hands me my change envelope and my Pagoda Phone for the night. Nate is cashing out his day-shift receipts on the computer behind the stainless-steel toppings island. “Yo, Vera! What’s shakin’?”

“Hey, Nate.”

“Anyone ever tell you that you look fine in that uniform?” he asks. He asks this at least twice a week. It’s his idea of endearing small talk.

“Only you,” I say.

“It’s like you were destined to be a pizza delivery technician,” he adds, then slams the cash drawer shut and struts into the back room with me, where he slaps a deposit bag onto the old desk in the office and removes his hokey MC Hammer leather coat from the hook on the back of the door.

“Destiny’s bullshit,” I answer. I should know. I’ve spent my whole life avoiding mine.

YOU’RE WONDERING WHERE MY MOTHER IS

My mother left us when I was twelve. She found a man who was not as parsimonious as my father and they moved to Las Vegas, Nevada, which is two thousand five hundred miles away. She doesn’t visit. She doesn’t call. She sends me a card on my birthday with fifty dollars in it, which my father nags me about until I finally go to the bank and deposit it. And so, for all six years she’s been gone, I have $337 to show for having a mother.

Dad says that thirty-seven bucks is good interest. He doesn’t see the irony in that. He doesn’t see the word interest as anything not connected to money because he’s an accountant and to him, everything is a number.

I think $37 and no mother and no visits or phone calls is shitty interest.

She had me when she was seventeen. I guess I should feel lucky that she stuck around the twelve lousy years she did. I guess I should feel lucky she didn’t give me up for adoption or abort me at the clinic behind the bowling alley that no one thinks we know about.

She and Dad grew up together, next-door neighbors. Just like Charlie and me. “I followed my heart,” he claims. Some good that did him. Now he’s stuck with me and three bookcases full of self-help Zen bullshit, has no friends, and maintains an amazing ability to blow off anything that’s remotely important.

When I turned thirteen, Dad told me the truth about Mom.

“I’m sure this will never come up, but in case it does, I want you to know the truth.”

Make a note. When a conversation starts out like this, brace yourself.

“When you were just a little baby, your mother took a job over at Joe’s.”

Of course, this meant nothing to me. I was thirteen. I had no clue that Joe’s was a bring-your-own-beer strip joint where women danced around half naked getting dollar bills stuffed into their panties.

“What’s Joe’s?”

With no shame or recognition of how badly I could take this, my father said, “A strip club.”

I knew what that was.

“Mom was a – a stripper?”

He nodded.

“And people know this?”

“Just people who were around back then – whoever knew her.” He struggled a bit then, seeing how disgusted I was. “It was only for a few months, Vera. She wanted her freedom back after dropping out of school, getting kicked out of her house, and having – uh – a baby so young. I was still drinking then. She wanted something that she never got back,” he said. The words came out garbled and stuttery. “She – she – uh – wanted something she never found until she ran off with Marty, I guess.”

Marty had been Mom and Dad’s podiatrist.

Dad and I used to sit in the waiting room and play twenty questions during Mom’s longer-than-normal appointments for verrucas.

Dad still hits an AA meeting when he needs to. He says it’s a curse – alcoholism. Says I should never even try the stuff because the curse runs in our family. “My father was a drunk, and so was his father.”

Well, if it’s as easy as catching my future from a blood relative, then I guess I’m due to be a drunk, pregnant, dropout stripper any day now.

Please Ignore Vera Dietz by A. S. King is available now at all bookshops, on the Text website (free postage) and as an ebook.