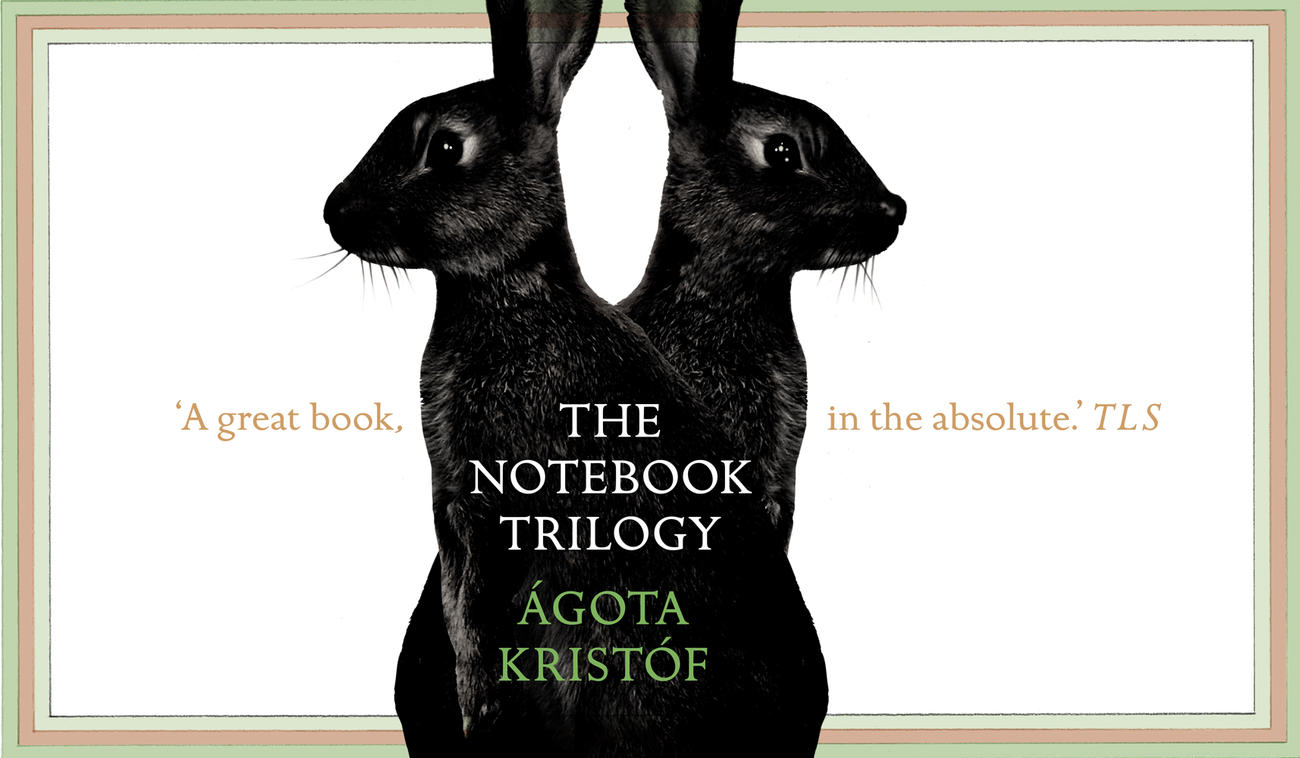

These three novels—The Notebook, The Proof and The Lie—tell the story of twin boys, Claus and Lucas, sent to live with their grandmother. She mistreats and neglects them, and to survive they abide by a new code of ethics. Spanning the Second World War and into the years of destructive postwater communism, The Notebook Trilogy is an unforgettable reading experience. Read an extract below.

ARRIVAL AT GRANDMOTHER’S

We arrive from the Big Town. We’ve been travelling all night. Mother’s eyes are red. She’s carrying a big cardboard box and we two boys are each carrying a small suitcase containing our clothes, plus Father’s big dictionary, which we take it in turns to carry since our arms get tired.

We walk for a long time. Grandmother’s house is a long way from the station, at the other end of the Little Town. There are no trams, buses or cars here. Just a few army trucks driving around.

There aren’t many people in the streets. The town is very quiet. Our footsteps echo on the pavement; we walk, without speaking, Mother in the middle, between the two of us.

When we get to Grandmother’s garden gate, Mother says:

‘Wait for me here.’

We wait for a while, then we go into the garden, walk round the house, and crouch down under a window, where we can hear voices. We hear Mother say:

‘There’s nothing more to eat at home, no bread, no meat, no vegetables, no milk. Nothing. I can’t feed them any more.’

Another voice says:

‘So you’ve remembered me. For ten years you didn’t give me a thought. You never came. You never wrote.’

Mother says:

‘You know why. I loved Father.’

The other voice says:

‘Yes, and now you remember that you also have a mother. You come here and ask me to help you.’

Mother says:

‘I’m not asking anything for myself. I just want my children to survive this war. The Big Town is being bombed night and day, and there’s no food left. All the children are being evacuated to the country, with relations or with strangers, anywhere.’

The other voice says:

‘So why didn’t you send them to strangers, anywhere?’

Mother says:

‘They’re your grandsons.’

‘My grandsons? I don’t even know them. How many are there?’

‘Two. Two boys. Twins.’

The other voice asks:

‘What have you done with the others?’

Mother asks:

‘What others?’

‘Bitches have four or five puppies at a time. You keep one or two and drown the others.’

The other voice laughs loudly. Mother says nothing, then the other voice asks:

‘They have a father, at least? You aren’t married, as far as I know. I wasn’t invited to any wedding.’

‘I am married. Their father is at the front. I haven’t had any news of him for six months.’

‘Then you can put a cross over him.’

The other voice laughs again. Mother starts crying. We go back to the garden gate.

Mother comes out of the house with an old woman.

Mother says to us:

‘This is your grandmother. You’ll be staying with her for a while—till the end of the war.’

Grandmother says:

‘It could last a long time. But I’ll put them to work, don’t you fret. Food isn’t free here either.’

Mother says:

‘I’ll send you money. Their clothes are in the suitcases. And there are sheets and blankets in the box. Be good, you two. I’ll write to you.’

She kisses us and goes away, crying.

Grandmother laughs very loudly and says:

‘Sheets and blankets! White shirts and patent-leather shoes! I’ll teach you what life is about!’

We stick out our tongues at Grandmother. She laughs even louder and slaps her thighs.

GRANDMOTHER’S HOUSE

Grandmother’s house is five minutes’ walk from the last houses in the Little Town. After that, there is nothing but the dusty road, blocked a bit further on by a barrier. It is forbidden to go any further, a soldier is on guard there. He has a machine-gun and binoculars and, when it rains, he takes shelter in a sentry box. We know that beyond the barrier, hidden by the trees, there’s a secret military base and, beyond the base, the frontier of another country.

Grandmother’s house is surrounded by a garden, at the bottom of which there is a stream, then the forest.

The garden contains all sorts of vegetables and fruit trees. In a corner, there’s a hutch, a hen-house, a pigsty and a hut for the goats. We have tried to climb on to the back of one of the biggest pigs, but it’s impossible to stay on.

The vegetables, the fruit, the rabbits, the ducks and the chickens are sold at the market by Grandmother, as well as the hens’ and ducks’ eggs and the goat’s cheese. The pigs are sold to the butcher, who pays for them with money, or with hams and smoked sausage.

There is also a dog to keep away thieves and a cat to keep away mice and rats. We mustn’t give the cat anything to eat, so that he’s always hungry.

Grandmother also owns a vineyard on the other side of the road.

You enter the house through the kitchen, which is large and warm. A fire burns all day long in the wood-stove. Near the window there’s a huge table and a corner bench. We sleep on the bench.

From the kitchen a door leads to Grandmother’s bedroom, but it’s always locked. Only Grandmother goes into it and, even then, only at night, to sleep.

There’s another room, which can be reached without going through the kitchen, directly from the garden. This room is occupied by a foreign officer. The door to that room is also locked.

Under the house there’s a cellar full of things to eat and, under the roof, an attic where Grandmother doesn’t go any more since we sawed away one of the rungs of the ladder and she fell and hurt herself. The entrance to the attic is just above the officer’s door and we get up there by means of a rope. It’s there that we hide the notebook, Father’s dictionary and the other things we have to hide.

We have now made a key, which opens all the doors in the house, and made holes in the attic floor. With the key we can move freely about the house when nobody’s in and, through the holes, we can observe Grandmother and the officer in their rooms, without anybody knowing.

GRANDMOTHER

Grandmother is Mother’s mother. Before coming to live in her house, we didn’t even know that Mother still had a mother.

We call her Grandmother.

People call her the Witch. She calls us ‘sons of a bitch’.

Grandmother is small and thin. She has a black shawl on her head. Her clothes are dark grey. She wears old army shoes. When it’s fine, she walks barefoot. Her face is covered with wrinkles, brown spots and warts with hairs growing out of them. She has no teeth left, at least none that can be seen.

Grandmother never washes. She wipes her mouth with the corner of her shawl when she has finished eating or drinking. She doesn’t wear knickers. When she wants to urinate, she just stops wherever she happens to be, spreads her legs and pisses on the ground under her skirt. Of course, she doesn’t do it in the house.

Grandmother never undresses. We have watched her in her room at night. She takes off one skirt and there’s another skirt underneath. She takes off her blouse and there’s another one underneath. She goes to bed like that. She doesn’t take off her shawl.

Grandmother doesn’t say much. Except in the evening. In the evening, she takes a bottle down from a shelf and drinks straight out of it. Soon she starts to talk in a language we don’t know. It’s not the language that the foreign soldiers speak, it’s a quite different language.

In that unknown language, Grandmother asks herself questions and answers them. Sometimes she laughs, sometimes she gets angry and starts shouting. In the end, almost always, she starts crying, she staggers into her room, drops on to her bed and we hear her sobbing long into the night.

OUR TASKS

We have to do certain jobs for Grandmother, otherwise she doesn’t give us anything to eat and leaves us to spend the night out of doors.

But at first we refuse to obey her. We sleep in the garden, and eat fruit and raw vegetables.

In the morning, before daybreak, we see Grandmother leave the house. She says nothing to us. She goes and feeds the animals, milks the goats, then takes them to the edge of the stream, where she ties them to a tree. Then she waters the garden and picks the vegetables and fruit, which she loads into her wheelbarrow. She also puts on to it a basket full of eggs, a small cage with a rabbit, and a chicken or duck with its legs tied together.

She goes off to the market, pushing her wheelbarrow with the strap around her scrawny neck, which forces her head down. She staggers under the weight. The bumps and stones in the road make her lose her balance, but she goes on walking, her feet turned inwards, like a duck. She walks to the town, to the market, without stopping, without putting her wheelbarrow down once.

When she gets back from the market, she makes a soup with the vegetables she hasn’t sold and jams with the fruit. She eats, she goes and has a nap in her vineyard, she sleeps for an hour, then she works in the vineyard or, if there is nothing to do there, she comes back to the house, she cuts wood, she feeds the animals again, she brings back the goats, she milks them, she goes out into the forest, comes back with mushrooms and kindling, she makes cheeses, she dries mushrooms and beans, she bottles other vegetables, waters the garden again, puts things away in the cellar and so on until nightfall.

On the sixth morning, when she leaves the house, we have already watered the garden. We take heavy buckets full of pig-feed from her, we take the goats to the edge of the stream, we help her load the wheelbarrow. When she comes back from the market, we are cutting wood.

At the meal, Grandmother says:

‘Now you know you have to earn your board and lodging.’

We say:

‘It’s not that. The work is hard, but to watch someone working and not do anything is even harder, especially if it’s someone old.’

Grandmother sniggers:

‘Sons of a bitch! You mean you felt sorry for me?’

‘No, Grandmother. We just felt ashamed.’

In the afternoon we go and gather wood in the forest.

From now on we do all the work we can.

THE FOREST AND THE STREAM

The forest is very big, the stream is very small. To get to the forest, we have to cross the stream. When there isn’t much water, we can cross it by jumping from one stone to another but, sometimes, when it has rained a lot, the water reaches up to our waist, and this water is cold and muddy. We decide to build a bridge with bricks and planks that we find around bombed houses.

Our bridge is strong. We show it to Grandmother. She tests it and says:

‘Very good. But don’t go too far into the forest. The frontier is nearby and the soldiers will shoot at you. And above all, don’t get lost. I won’t come looking for you.’

When we were building the bridge, we saw fish. They hide under big stones or in the shadow of bushes and trees, whose branches meet in places over the stream. We choose the biggest fish. We catch them and put them in a watering-can filled with water. In the evening, when we take them back to the house, Grandmother says:

‘Sons of a bitch! How did you catch them?’

‘With our hands; it’s easy. You just have to stay still and wait.’

‘Then catch a lot. As many as you can.’

Next day, Grandmother puts the watering-can on her wheelbarrow and she sells our fish at the market.

We often go into the forest, we never get lost, we know where the frontier is. Soon the guards get to know us. They never shoot at us. Grandmother teaches us to know the difference between mushrooms you can eat and the poisonous ones.

From the forest we bring back firewood on our backs, and mushrooms and chestnuts in baskets. We stack the wood neatly against the walls of the house under the leanto and we roast chestnuts on the stove if Grandmother isn’t there.

Once, in the forest, beside a big hole made by a bomb, we find a dead soldier. He is still all of a piece, only his eyes have gone because of the crows. We take his rifle, his cartridges and his grenades: we hide the rifle inside a bundle of firewood, and the cartridges and grenades in our baskets, under the mushrooms.

When we get back to Grandmother’s, we carefully wrap these objects in straw and potato sacks, and bury them under the seat, in front of the officer’s window.

DIRT

At home, in the Big Town, Mother often used to wash us. In the shower or in the bath. She put clean clothes on us and cut our nails. She used to go with us to the barber’s to have our hair cut. We used to brush our teeth after every meal.

At Grandmother’s it is impossible to wash. There is no bathroom, there isn’t even any running water. We have to go and pump water from the well in the yard, and carry it back in a bucket. There is no soap in the house, no toothpaste, no washing powder.

Everything in the kitchen is dirty. The red, irregular tiles stick to our feet, the big table sticks to our hands and elbows. The stove is completely black with grease and the walls all around are black with soot. Although Grandmother washes the dishes, the plates, spoons and knives are never quite clean and the saucepans are covered with a thick layer of grime. The dishcloths are discoloured and have a nasty smell.

At first we didn’t even want to eat, especially when we saw how Grandmother cooked the meals, wiping her nose on her sleeve and never washing her hands. Now we take no notice.

When it’s warm we go and bathe in the stream, we wash our faces and clean our teeth in the well. When it’s cold, it’s impossible to wash properly. There is no receptacle big enough in the house. Our sheets, our blankets and our towels have disappeared. We never see again the big cardboard box in which Mother brought them.

Grandmother has sold everything.

We’re getting dirtier and dirtier, our clothes too. We take clean clothes out of our suitcases under the seat, but soon there are no clean clothes left. Those we are wearing are getting torn and our shoes are wearing through. When possible, we walk barefoot and wear only underpants or trousers. The soles of our feet are getting hard, we no longer feel thorns or stones. Our skin is getting brown, our legs and arms are covered with scratches, cuts, scabs and insect bites. Our nails, which are never cut, break, and our hair, which is almost white because of the sun, reaches down to our shoulders.

The privy is at the bottom of the garden. There’s never any paper. We wipe ourselves with the biggest leaves from certain plants.

We smell of a mixture of manure, fish, grass, mushrooms, smoke, milk, cheese, mud, clay, earth, sweat, urine and mould.

We smell bad, like Grandmother.

EXERCISE TO TOUGHEN THE BODY

Grandmother often hits us, with her bony hands, a broom or a damp cloth. She pulls our ears and catches us by the hair.

Other people also hit and kick us, we don’t even know why.

The blows hurt and make us cry.

Falls, scratches, cuts, work, cold and heat can also cause pain.

We decide to toughen our bodies in order to be able to bear pain without crying.

We start by hitting and then punching one another. Seeing our swollen faces, Grandmother asks:

‘Who did that to you?’

‘We did, Grandmother.’

‘You had a fight? Why?’

‘For nothing, Grandmother. Don’t worry, it’s only an exercise.’

‘An exercise? You’re crazy! Oh well, if that’s your idea of fun . . .’

We are naked. We hit one another with a belt. At each blow we say:

‘It doesn’t hurt.’

We hit harder, harder and harder.

We put our hands over a flame, we cut our thighs, our arms and chests with a knife and pour alcohol on to our wounds. Each time we say:

‘It doesn’t hurt.’

After a while, in fact, we no longer feel anything. It’s someone else who is hurt, someone else who gets burnt, cut and feels pain.

We don’t cry any more.

When Grandmother is angry and shouts at us, we say:

‘Stop shouting, Grandmother, hit us instead.’

When she hits us, we say:

‘More, Grandmother! Look, we are turning the other cheek, as it is written in the Bible. Strike the other cheek, Grandmother.’

She answers:

‘May the devil take you with your Bible and your cheeks!’