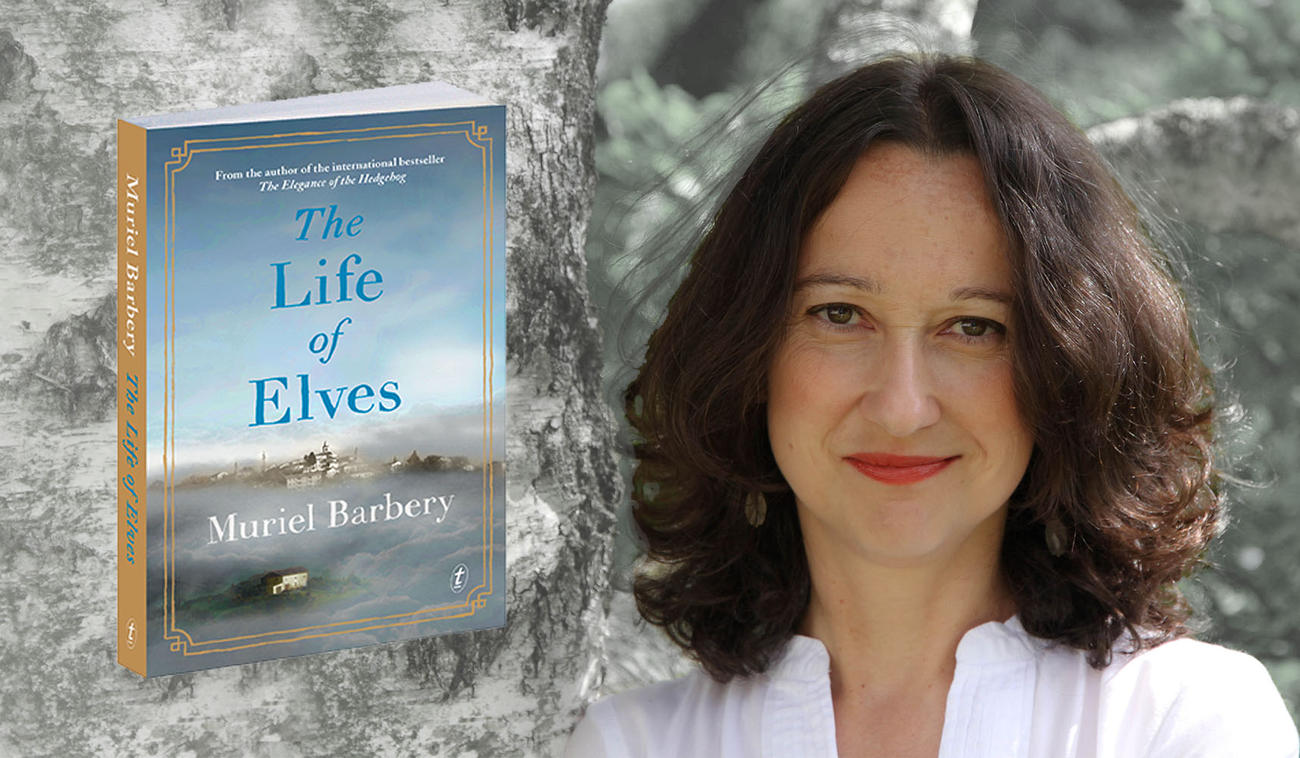

Muriel Barbery’s The Elegance of the Hedgehog was published in forty-three countries, spent more than sixty weeks on the New York Times bestseller lists and sold millions of copies worldwide. Seven years after the publication of her international bestseller, Barbery returns with a moving novel about the quest for enchantment in a world that seems to have forgotten such a thing ever existed. Read on to discover her inspirations for this wonderful book.

Muriel Barbery is visiting Australia and New Zealand next month for the launch of The Life of Elves. Check her events list here. We also have book club notes here.

The Life of Elves opens with two fairytales, the stories of Maria and Clara. Can the whole book be read as a fairytale, or a parable?

Apart from the beginning, I don’t see the novel as a fairytale, though it borrows certain elements of the genre, and from the world of fantasy, but also from a kind of literature of the land. I don’t think it’s a parable either. In fact, I don’t really know what it is: that’s for the reader to decide.

And the elves aren’t much like those we’ve read about in fairytales…

For a long time, I wasn’t sure if they should be real or just imagined, and in the end there’s no way of telling. But they took the shape the novel naturally gave them, which was to be at one with nature and the animal world, which explains the strange form they took.

The theme of harmony, in particular harmony with nature, runs through the book…

One of the sparks for the novel was a phrase I came across in Kakuzô Okakura’s Book of Tea, written in 1906, in which he speaks nostalgically about Ancient China, which gave Japanese art some of its most beautiful artefacts. But he laments that Chinese people have become ‘modern, that is to say, old and disenchanted’. I’m fascinated by this incredibly clear and concise characterisation of a modern world cut off from all enchantment and, by the same token, from its poetic illusions. And this sense of enchantment, whether poetic or natural, ended up being both the starting point and the guiding force for this novel.

Another phrase, or rather motto, ‘Je maintiendrai’ (I will maintain) seems equally important…

I’ve always been intrigued by this motto, originally that of the Princes of Orange, because of its enigmatic form: it almost looks grammatically wrong, as you expect it to have an object. In the book, the elf world in particular is one in which they are trying to maintain the powers of nature and art, to hold them together. But in this first volume, the motto remains intentionally ambiguous.

Could the elf world therefore be seen as the world of the arts, in opposition to the world of technology, as embodied by the disturbing figure of the Governor?

In actual fact, the same fault line, the same disenchantment and the same threat weigh upon the human world as on that of the elves.

Flowers and gardens also play a large part in the book…

Yes. Hawthorn, violets, and especially the little irises you get in Japan, Iris japonica, which has been my favourite flower ever since I discovered it. Another spark which set me off writing The Life of Elves was a conversation I had with a friend about Japanese gardens and the French idea of natural beauty. I told him I thought Japanese gardens had something elf-like about them, while the French aesthetic when it comes to nature is human, and with that a key part of the novel was born. But something else which I think goes hand in hand with this is my appreciation of books on herbal remedies and encyclopaedias of medicinal plants, and of the days when people looked to nature for the basis of their cures, and gave plants and flowers a symbolic language which I also find deeply poetic.

The language of this novel is new for you, a unique combination of simultaneous richness and simplicity…

The language came naturally as I was writing the original fairytale, and it carried the story along. It immediately took on a timeless quality, but with an intentionally archaic ring, with the result that it is difficult to situate it in a particular time or literary style. The same goes for the story the novel tells.

The writing also leads the reader to read at a particular pace…

I think you have to subscribe to the style in order to get into the story. Writing in the third person for the first time opened up a whole range of linguistic options and a fertile breeding ground for new narrative possibilities. It was damn hard work: I had to keep reworking the text and it was often a difficult, complicated and frustrating experience, but it was always stimulating and, ultimately, joyful.

Interview copyright © Gallimard 2015.