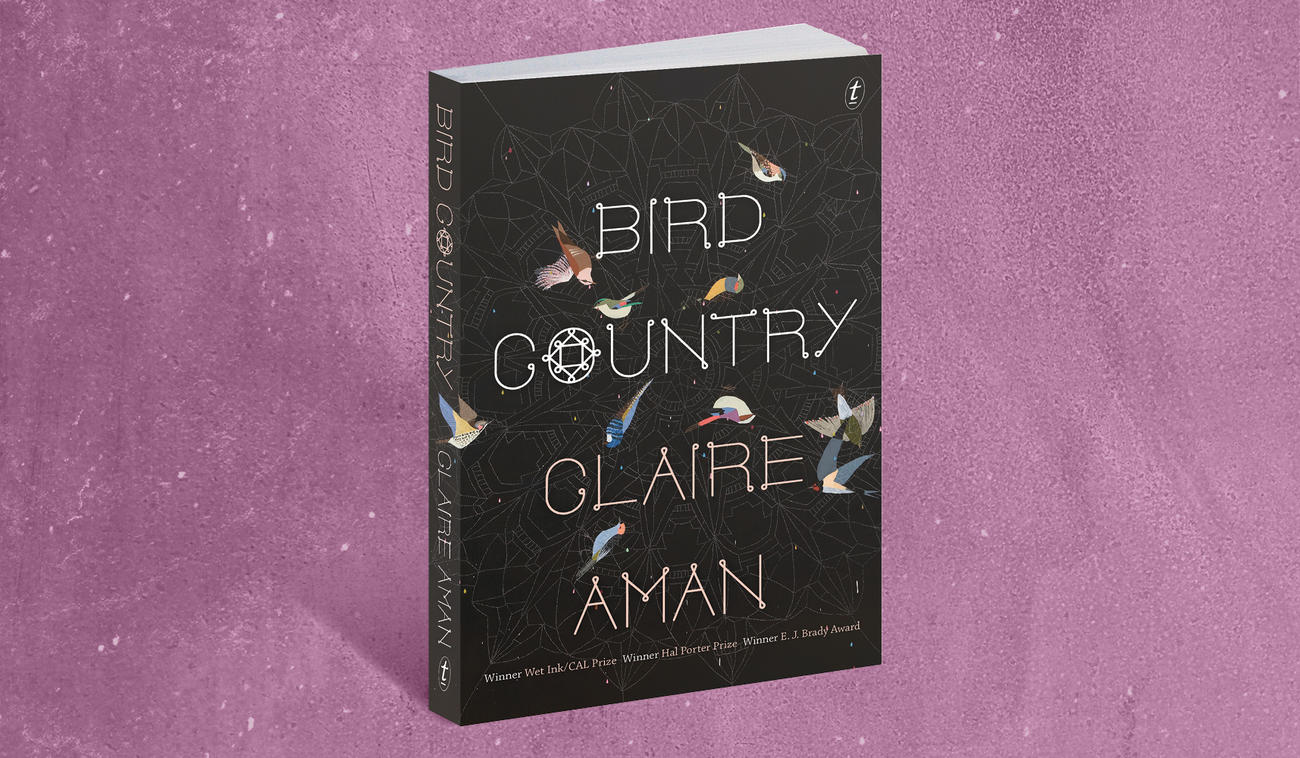

Bird Country, the sparkling debut from Claire Aman is out this month through Text.

This is a poignant and powerful collection of portraits of ordinary people in rural Australia.

A boat trip in a squall to scatter the ashes of an old man, who was not loved.

A young father, driving his daughters home across grass plains, unable to tell them that their mother has died.

A speech that doesn’t include the aching pain of trying to save a cousin’s life.

A mother hiding her fugitive son in a cockatoo cage as the river rises.

A man pouring his life into finding the perfect stained glass after his wife has left him.

A woman longing for the right person to tell about her sister’s death, while she works nightshift at a roadhouse.

These are moving and evocative stories about love and loss and yearning – and the things we don’t say.

Bird Country launched earlier this month with an insightful speech by Cate Kennedy at Readings in St Kilda, and we thought we’d share it with you:

Cate Kennedy

Speech for the launch of Bird Country by Claire Aman

It’s a pleasure to be asked to launch Claire Aman’s fresh-minted new collection of stories Bird Country, although of course this new publication hardly springs out of nowhere—these stories first began appearing in journals and anthologies from 2007 or so, and I’m sure many have had their original genesis many years before then. In fact, as Claire is the winner of the WetInk/CAL prize, the Hal Porter Prize and the E. J. Brady Prize, among others, the wonder is why actual publication of the whole collection has taken so long. But that’s the way it is with stories, and certainly the way it is with stories I love and return to the most—they take time to develop and polish, and they somehow reflect not just the intensity of particularity, but the shifts and alterations in the writer’s own focus, the circling of their material. In reading them I was reminded of something I heard the writer Thomas Chatterton Williams say in a talk he gave on finding the universal in the particular in the stories we write: 'What’s infusing it? What’s the urgency? What’s the belief?’ From the astute photographer putting two and two together at a strange and fearful wedding to the man on a road trip with his daughters who just can’t find the moment to tell them their mother has died, you know from the moment you dive into this collection that you’re in the hands of someone who has taken the time to mull over and polish each element, and fit it carefully and skilfully into place in every story here.

The writer Toni Jordan, who launched Chris Womersley’s City of Crows last week at Readings, spoke of the pleasure of stepping into a story like a boat, pushing away from your moorings and letting it take you somewhere. The pleasure, I think, lies also in knowing it’s a well-made boat—shipshape and sturdy, lovingly made, just the right size for the journey. No wonder small boats are called ‘craft’! And the materials the crafted boat is made from take time to create and cut to size, to sand back to bring out the grain, to test for seaworthiness. The plots find some current and take us along on an unexpected rip, and the narrative voices Claire Aman has created open up a private predicament to us, then some new pattern or metaphor will emerge and something focuses in the story. Before we know it we are suddenly making landfall in the psyche of another person—a young woman working at a dead-end outback servo for whom the glimmer of escape seems barely possible, a damaged ex-addict and a young boy who bond over how best to care for a bird, the handyman who forms an alliance with an elderly woman struggling to maintain her dignity and autonomy.

These characters are rendered in such a way that whole lives are suggested by a throwaway comment or telling gesture. Whether they are written in first, second or third person, what is evident is the care the author has taken to give them dimension and agency, which requires more than just skill. It requires a compassionate eye and a belief in at least the possibility of redemption, despite our fallibility. And running like a thread through many of them are birds—innocent, imperilled, endangered, bought and sold, common and rare. The troubled sense of protectiveness these animals bring out in Claire’s characters (and in her readers, compellingly drawn into her stories) provides a kind of resonant unity to the whole, undercutting this chorus of distinctive, memorable human voices with vulnerability, and exploring what we do with vulnerability.

This is what stories do, too. We produce them in solitude and isolation and then stand on our flawed small vessels and send them out like that small bird across the horizon, our envoys. One day, back they come, with a small green shoot in their beak, evidence of something growing into leaf in a place we can hardly imagine.

I commend Text for producing such a poised and polished collection from such a distinctive voice, and you, Claire, for the long slow polishing and sanding which has brought it to this state of burnished gleam. I commend it to readers, and invite you to immerse yourselves in some worlds which are not your own but feel strangely real and recognisable, and to launch it…as in push it gently away from the mooring, seeing it set sail and imagining where it will find landfall, its reader safely aboard, stepping onshore somewhere new and unexplored.

Thanks,

Cate Kennedy

Read the story ‘Milk Tray’ from Claire Aman’s Bird Country and find yourself journeying on a very well-made craft indeed.

This is to say I didn’t take the old lady’s things for myself, I was only looking after them. I wanted to leave the chocolate box in her garden so when she lifted the lid she’d find her rubies and diamonds and pearls, each one tucked in its own dark nest. It was nearly ready, only two more to go – Turkish Delight and Peppermint Creme. She would have understood. But it’s too late, and now I can’t decide if I should bury the box down at the river or flog the lot and go to Bali.

I’m the mower-man. That’s how I met her. The last couple of years I did other things for her too, shopping, hang out the washing. I even cut her toenails. She had my phone number on her speed dial. I helped her vote the time she couldn’t remember who was who. She used to be a professor back when women were under the thumb, so she must have been smart. All the same, she found it hard to string her thoughts together by the end. Not that I’m a genius myself. I suppose I’m more of an artist, with my bits of wood carving.

You’re a rough diamond, Budgie, she’d tell me. You could tell she was from a wealthy background by the way she said it. You’re a helpful soul, she’d say. But she helped me too, because I grew my secret pot down on her riverbank in a clearing, just half-a-dozen plants. If anyone had found it I would have owned up. But no one ever did, and my annual crop grew hairy-budded and fragrant down there in that soft brown soil.

Just the back lawn, Budgie, she’d say. Leave the riverbank wild. Other people whose gardens stretch down to the river ask me to mow all the way to the water, like a park. Not Esther. She had shoulder-high sedges, and sandpaper figs and bottlebrushes and silky oaks, and my pot.

There were certificates in her hallway from the Royal this and the Society of that. She lent me a book she’d written.Concepts of Geomorphology, by Esther Osram.

The first paragraph went like this: The surface of Earth is constantly changing. Just look at waves on a beach. A ripple in the sand may form in a minute, but mountains can take hundreds of millions of years.

The book talked about how landscapes are formed. Things get compressed and uplifted, they fold and buckle and crumple; pieces tumble and slide off and some of it gets blown around or washed down and everything becomes part of something new. Reading it made me think of Esther as a weathered old land, all scored with crooked channels, erosion lines gullying down from her nose and a seep of spit shining at the corner of her mouth. You could see how the constant inward movement of her brows had pushed in a deep fold between her eyes. She looked more like a geological feature than a professor of it. I got the idea of writing a sort of geological poem about ancient people, but like most of my poetry it never got past inspiration phase.

At the end, the book said, surprisingly, that no one really knows the truth.

When I went to return it she said you have it, Budgie, you keep it. That was funny. If I’d written a book, even one on geology, it would be my most treasured possession. I wouldn’t just give my copy to the mower-man. But she insisted. I thought, you’re losing your mind, Esther, but I said thank you very much and I went down the street and bought her a box of Milk Tray chocolates. Remember them? They were classy in their time – the purple box with its embossed silver border, white ribbon unfurling to spell Milk Tray. A fine selection of milk chocolates. I got the box of twenty-four. I know there are more sumptuous chocolates, but I thought she’d enjoy the old Milk Tray.

I was right. Her fingers reminded me of old claws the way she scrabbled at the cellophane but I didn’t interfere, and she finally had it open. You go first, Esther, I said, and she took one and held it up. Praline Passion, I read from the lid. Satiny hazelnut praline. I took a Caramello Pleasure wrapped in red tinfoil. Full of silky flowing caramel.

It’s like a jewellery box, she said, and it was. It’s the moment when you lift the corrugated paper to find Macadamia Heaven in gold foil, bevelled Turkish Delight with its promise of a gleaming rose centre, velvety Hazelnut Supreme tucked in its own oval hollow. Gold and silver, rubies and emeralds. She asked me, after we’d eaten three each, if I’d take the rest home. As I left she grabbed me hard by the arm. The baubles, Budgie, she said. We don’t need to keep them here, do we? Nothing stays in the one place forever, she said. Not forever.

I ate the rest of the chocolates in bed, dreaming of how, in the night, a sleeping woman might tuck her hand into mine, and how that could feel like a gemstone nestling in deep blue velvet.

The secret to starting any lawn mower is to turn it on its side for ten seconds. It never fails. I’ve never needed to advertise my gardening business, not even when I started. People like it if you’re cheerful and reliable. They tell their friends. And I earn enough money to keep myself going.

Esther’s house faces the river with its back to the street. It’s my favourite garden. You want to lie down in that soft grass and stare into the dark canopies of the trees. It has jacarandas and hibiscus and camellias heavy with ice pinks and ruby reds, and a ferny path winding through masses of blue hydrangeas and gardenias to a birdbath. There’s an old avocado tree at the bottom, and beyond that, the long riverbank with its rushes and reeds.

I started finding the jewellery last Easter. First it was the pearls. The silvery-cream balls were arranged in a curving line on the mossy rim of the birdbath. They gleamed and clacked in my hand. When I told Esther she laughed. Did the garden make a pearl in the night, Budgie?

I left them in a saucer on her kitchen table. When I came back the following week there they were again, laid out on the soft green moss. They were her things and I wasn’t in charge of her, so I left them. They acquired a pale green patina in that shady spot, and after a month or so you could barely notice them.

Pearls, the housework of oysters. Meanwhile, Esther’s niece Joy was also thinking about housework. Joy lives in a new subdivision, fifteen minutes away by Peugeot. It took her two years to ever say hello to me, even though she knew I helped Esther. Maybe she felt guilty when Esther told her what a rough diamond I was.

You could say Joy meant well. But she had a habit oftalking about Esther as if she wasn’t there. Once she told me Esther had become smelly, right in front of her.

When Joy discovered an old chop in Esther’s cutlery drawer, she sent in the services. People started knocking on the door and inviting themselves in. They called me Essie, she said. That’s a little girl’s name. They called me darling. As if they were the adults, the fat things.

Joy organised the home care to come once a week. But Esther preferred me to be the one putting the clothes through the washing machine or running a wettex around the kitchen sink. I didn’t fuss. The cleaner complained about smells and stains and rearranged Esther’s cupboards so she couldn’t find anything.

I’d always been happy to take her shopping. She’d run her comb under the kitchen tap and plaster her hair back in furrows, and she’d sit up straight in my ute holding her handbag on her lap. In the supermarket she’d sing out all the sweet things she needed, the Swiss Rolls and pink iced buns and the Chocolate Royals.

She told me Joy was talking about nursing homes. But I’ve lived here for fifty years, she told me, and her hands held the porch rail tight. I was a geologist, she said, and a bride. The north wind blew hot dust over the wedding guests, and we danced with our dresses streaming southwards. I had diamond earrings, she told me.

I found one of them sparkling in a pale nest of camelliapetals on the garden path. It was only because the sun caught it that I noticed. I asked her later while we were having our cup of tea. Diamonds? I wore history in my ears, she said. Nothing goes back to its original state, Budgie.

The other earring was hanging on a twig on the avocado tree.

I decided to put everything in the empty chocolate box, which was still lying beside my bed.

I’ve been reading in a magazine about a famous painter who suffers from Korsakoff syndrome. Conversations with him are described as groping in a maze of fragments and finding the odd tiny jewel. Korsakoff is an end stage of alcoholism and also an effect of vitamin B deficiency. You can’t recognise your own memories, so you invent connections between the oddments you can still conjure. As if the thoughts have become unstrung. Esther wasn’t like that. The old painter wears nappies and makes up wild stories. Esther just brought her jewellery out, piece by piece, to the garden. And I brought each shining thing home for the Milk Tray box. I was going to leave it, once it was full, under the birdbath. She must have noticed things weren’t where she left them, but she never said anything. Nor did I. They were her baubles and if she didn’t want them up in the house, that was all right with me. I was only looking after them. Like she said, nothing stays in one place forever.

Esther’s book said the faces of tableland escarpments are notched and etched by ravines and promontories. The joints weather from behind, and portions of the rock mass are detached. Piles of talus, the rocks dislodged from above, lie against the base of the escarpment, all fallen.

I didn’t tell anyone about the jewellery because no one would have understood. That’s the way people are, they don’t understand. It’s why I keep my poetry to myself.

One morning Esther rang me early to say she’d hurt herself. I arrived to find her in the kitchen, red footprints on the lino, a red pool shining at her feet. Hoy, Budgie, she said. She pulled up the hem of her nightie to show her shin. Her skin was like layers of tissue paper and the blooms kept welling up. She told me where to find a bandage. Then I cleaned up the mess. There was a red trail spattering down the steps. It led to a magnolia tree where a ruby necklace, glittering with pink light, dangled from a branch.

The point seems to be that everything shifts, Budgie, she told me when I came back inside. There was a dry leaf stuck to the lapel of her dressing-gown.

When I left the house, Joy was outside with a fellow wearing sunglasses and a tie. Real estate agent, I thought. After he’d driven away, Joy insulted me. She said she wasn’t sure how to put it, but she hoped that, well, I wouldn’t feel obliged anymore. Lonely old people. You know. Inappropriate. She said from now on the services would look after Esther. There would be a bed soon, in a nursing home. I felt like saying yeah, Joy, a nursing home’s really going to do the right thing by Esther.

I’ve been thinking about the sound of Esther’s voice, thin and deep like the wind in the leaves. She needed someone she could trust. She could be your mother hiding food in her drawer or leaving the stove on. I was never after her things.

What happened next was the cut on her leg became a shining ulcer. A nurse came each morning to change the dressing. I kept on visiting. Esther found it hard to walk, and I brought her the pink iced buns from the supermarket. The jewellery kept appearing in the garden, but it wasn’t artfully placed anymore. A heart-shaped gold locket gleamed at the foot of the steps, smooth and rich like a real heart. I didn’t open it; they were her interiors, not mine. On the little path was a watch with a broken face and a swirl of emeralds on the band. I pricked my finger on a brooch the colour of Turkish Delight when I pulled a clump of ferns away from the path. The Milk Tray was nearly complete.

Last Friday morning I rang her as usual. She said she didn’t need anything but she’d slept badly and the morning had taken a long time to arrive. She told me Hindus understood the slow pace of time and how long everything takes. Hindus and geologists, Budgie, she said. Then she told me I was a rough diamond.

I drove past just as the sun was going down, on my wayback from a pruning job. There was no answer when I rang the doorbell so I went around to the other side of the house. Unusually, the door was closed. Esther’s lawn was due for a cut, there was a wind rippling through the grass like an invisible hand stroking a cat. I followed the ferny path past the blue-headed hydrangeas, past the birdbath, down past the avocado tree to the whisper of a track through the rushes and reeds on the riverbank. I was very quiet. There was something further down. Through the trees I saw Esther lying on a green bed of reeds in her ruby-red dressing-gown, her head on a dark blue cushion.

If it had been anyone else lying there, I would have called an ambulance. I did what I did because she trusted me. I knew what she wanted. You might think it was wrong. You might think I was stealing her jewellery, too. I hope not.

Anyway, I walked back up to Esther’s garden and I lay down in the grass, and I looked up into the flowered canopy and listened to the wind.

Next morning I harvested my pot early. Then I made the phone call. When they carried her up under a sheet, she was like a snowy old land with outcrops and scarps and uplands, all white in the morning sun.

We told you she was brilliant.

Bird Country by Claire Aman is available now in all good bookshops, on the Text website (free postage!) and in eBook.

Until next time,

Keep reading,

The Texters.