Text has recently published Draft No. 4: On the Writing Process, the long-awaited guide to writing long-form non-fiction by the legendary author and teacher by John McPhee. It derives from eight essays on the writing process that have appeared in the New Yorker.

In Draft No. 4 John McPhee shares insights gained and refined over his long career teaching at Princeton University, where he has nurtured some of the most highly regarded writers of our time. He discusses structure, diction and tone, observing that ‘readers are not supposed to notice the structure. It is meant to be about as visible as someone’s bones’.

This book is a vivid depiction of the writing process, enriched by personal reflections on the life of a writer and McPhee’s keen sense of writing as a way of being in the world.

‘In the grand cosmology of John McPhee... every part of time touches every other part of time. You just have to find the right structure.’

— New York Times Magazine

Read an excerpt from this fascinating book:

In the late nineteen-sixties, I was working in rented space on Nassau Street up a flight of stairs and over Nathan Kasrel, Optometrist. Across the street was the main library of Princeton University. Across the hall was the Swedish Massage. Operated by an Austrian couple who were nearing retirement and had been there for decades, it was a legitimate business. They massaged everything from college football players to arthritic ancients, and they didn’t give sex. This, however, was the era when massage became a sexual synonym, and most evenings – avoiding writing, looking down from my window on the passing scene – I would see men in business suits stop, hesitate, look around, and then move toward the glass door at the foot of the stairs. Eventually, the Austrians had to scrape the words “Swedish Massage” off the door, and replace them with a hanging sign they removed when they went home at night. Meanwhile, the men kept arriving at the top of the stairs, where neither door was marked. When they knocked on mine and I opened it, their faces fell dramatically as the busty Swede they expected turned into a short and bearded man.

In this context, I wrote three related pieces that became a book called Encounters with the Archdruid. To a bulletin board I had long since pinned a sheet of paper on which I had written, in large block letters, ABC/D. The letters represented the structure of a piece of writing, and when I put them on the wall I had no idea what the theme would be or who might be A or B or C, let alone the denominator D. They would be real people, certainly, and they would meet in real places, but everything else was initially abstract.

That is no way to start a writing project, let me tell you. You begin with a subject, gather material, and work your way to structure from there. You pile up volumes of notes and then figure out what you are going to do with them, not the other way around. In 1846, in Graham’s Magazine, Edgar Allan Poe published an essay called “The Philosophy of Composition,” in which he described the stages of thought through which he had conceived of and eventually written his poem “The Raven.” The idea began in the abstract. He wanted to write something tonally sombre, sad, mournful, and saturated with melancholia, he knew not what. He thought it should be repetitive and have a one-word refrain. He asked himself which vowel would best serve the purpose. He chose the long “o.” And what combining consonant, producibly doleful and lugubrious? He settled on “r.” Vowel, consonant, “o,” “r.” Lore. Core. Door. Lenore. Quoth the Raven, “Nevermore.” Actually, he said “nevermore” was the first such word that crossed his mind. How much cool truth there is in that essay is in the eye of the reader.

Nonetheless, I was doing something like it when I put ABC/D on the wall. For more than a decade, first at Time magazine and then at The New Yorker, I had been writing profiles – each, by definition, portraying an individual. At Time, I did countless sketches, long and short, of show-business people (Richard Burton, Sophia Loren, Barbra Streisand, et al.), and at The New Yorker even longer pieces, on an athlete, a headmaster, an art historian, an expert on wild food. After ten years of that, I was a little desperate to escalate, or at least get out of a groove that might turn into a rut.

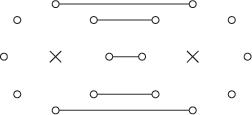

To prepare a profile of an individual, the reporting endeavor looks something like this:

The X is the person you are principally going to talk to, spend time with, observe, and write about. The O’s represent peripheral interviews with people who can shed light on the life and career of X – her friends, or his mother, old teachers, teammates, colleagues, employees, enemies, anybody at all, the more the better. Cumulatively, the O’s provide triangulation – a way of checking facts one against another, and of eliminating apocrypha. Writers like Mark Singer and Brock Brower have said that you know you’ve done enough peripheral interviewing when you meet yourself coming the other way.

So, after those ten years and feeling squeezed in the form, I thought about doing a double profile, through a process like this:

In the resonance between the two sides, added dimension might develop. Maybe I would twice meet myself coming the other way. Or four times. Who could tell what might happen? In any case, one plus one should add up to more than two.

Then who? What two people? I thought of various combinations: an actor and a director, a pitcher and a manager, a dancer and a choreographer, a celebrated architect and a highly successful bullheaded client, 1 + 1 = 2.6. One day while I was still undecided, I happened to watch on CBS a men’s semifinal in the first United States Open Tennis Championships. Two Americans – one of them twenty-five years old, the other twenty-four – were playing each other. One was white, the other black. One had grown up beside a playground in inner-city Richmond, the other on Wimbledon Road in Cleveland’s wealthiest suburb. On their level are so few tennis players – and the places they compete are so organized nationally – that these two would have known each other since they were eleven years old. For something like three weeks, I kept thinking about that combination and its possibilities, and then decided to attempt a double portrait, letting the match itself contain and structure the story. I would not be able to do that without a copy of the CBS tape. In those days, tapes were not archived. They saw repeated use. The copying would have to be done as something called a kinescope – a sixteen-millimeter film shot from a television monitor. I asked William Shawn, The New Yorker’s editor, if he would pay for the kinescope. “Very well,” he said, sighing. “Go ahead.” I called CBS. A guy there said, “You haven’t called a minute too soon. That tape is scheduled to be erased this afternoon.”

Called “Levels of the Game,” the double profile worked out, and my aspirations went into a vaulting mode. If two made sense, why not four people in one complex piece of writing? That was when I put the block letters on the bulletin board. A, B, and C would be separate from one another, and each would interact with D, yes, but who were these people? As things would eventuate, the two projects I am describing (1 + 1 = 2.6 and ABC/D) would be the only ones I would ever do that began as abstract expressions in search of subject matter. Quoth the raven, “Nevermore.” Meanwhile, there was still no theme for the quadripartite profile. What to write about?

As I have noted in (among other places) the introduction to a book of excerpts called Outcroppings, a general question about any choice of subject is, Why choose that one over all other concurrent possibilities? Why does someone whose interest is to write about real people and real places choose certain people, certain places? For nonfiction projects, ideas are everywhere. They just go by in a ceaseless stream. Since you may take a month, or ten months, or several years to turn one idea into a piece of writing, what governs the choice? I once made a list of all the pieces I had written in maybe twenty or thirty years, and then put a check mark beside each one whose subject related to things I had been interested in before I went to college. I checked off more than ninety per cent.

My father was a medical doctor who dealt with the injuries of Princeton University athletes. He also travelled the world as the chief physician of several United States Olympic teams. When I was very young, he spent summers as the physician at a boys’ camp in Vermont. It was called Keewaydin and was a classroom of the woods. It specialized in canoe trips and taught ecology in our modern sense when the word was still connoting the root-and-shoot relations of communal plants. Aged six to twenty, I grew up there, ending as a leader of those trips. I played basketball and tennis there, and on my high-school teams at home, with absolutely no idea that I was building the shells of future pieces of writing. I dreamed all year of the trips in the wild, not imagining, of course, that they would eventually lead to the Brooks Range, to the Yukon-Tanana suspect terrain, to the shiplike ridges of Nevada and the Laramide mountains of Wyoming, or that they would lead to the rapids of the Grand Canyon in the company of C over D.

The environmental movement was in its early stages in the nineteen-sixties, and I decided that it would be the subject of ABC/D, pitting an environmentalist against three natural enemies. Easier said than arranged. I still had no inkling who these people might be. In fact, if their names had somehow magically appeared before me I would not have recognized any of them. For help, I went to Washington, where my friend John Kauffmann, with whom I had once taught school, worked for the National Park Service as a planner. Components of the park system that have resulted from his studies are, among others, Cape Cod National Seashore and Gates of the Arctic National Park. With several of his colleagues and friends, we developed lists of possibilities, first for D. We were looking for people in the category of the late Aldo Leopold, “the father of wildlife ecology,” whose A Sand County Almanac had sold two million copies; but he would have been too reasonable, as were other leading environmentalists of the day, with a bristly exception. David Brower, executive director of the Sierra Club, was described by Kauffmann and company as a feisty take-no-prisoners unilateral thinker with tossing white hair like a Pentateuchal prophet. He had a phone number in area code 415. I called him up. Several days later, he called back to say that he would do it. Meanwhile, A, B, and C – the three natural enemies – were easier to identify than to choose, and, seeking no input whatever from Brower, we made a list of seventeen. Several months later, it had been reduced to three, and among them was Floyd Dominy, the United States Commissioner of Reclamation. He built very big Western dams, and he was a very tough Western guy. As a young county agent in Wyoming, he had helped ranchers through drought after drought, and he deeply believed in the impoundment of water. In congressional hearings, he had fought Dave Brower over potential dam sites from Arizona to Alaska, and now and again Brower had defeated him. Dominy looked upon Brower as a “selfish preservationist.” In an early interview at Dominy’s office in the Department of the Interior, he said to me, “Dave Brower hates my guts. Why? Because I’ve got guts.” As that conversation would play out in the eventual piece, Dominy went on to say,

“I can’t talk to Brower, because he’s so God-damned ridiculous. I can’t even reason with the man. I once debated with him in Chicago, and he was shaking with fear. Once, after a hearing on the Hill, I accused him of garbling facts, and he said, ‘Anything is fair in love and war.’ For Christ’s sake. After another hearing one time, I told him he didn’t know what he was talking about, and said I wished I could show him. I wished he would come with me to the Grand Canyon someday, and he said, ‘Well, save some of it, and maybe I will.’ I had a steer out on my farm in the Shenandoah reminded me of Dave Brower. Two years running, we couldn’t get him into the truck to go to market. He was an independent bastard that nobody could corral. That son of a bitch got into that truck, busted that chute, and away he went. So I just fattened him up and butchered him right there on the farm. I shot him right in the head and butchered him myself. That’s the only way I could get rid of the bastard.”

“Commissioner,” I said, “if Dave Brower gets into a rubber raft going down the Colorado River, will you get in it, too?”

“Hell, yes,” he said. “Hell, yes.”

Want to know what happened next?

Draft No. 4: On the Writing Process by John McPhee is out now at all good bookshops, from the Text website (Free postage!) and as an ebook.