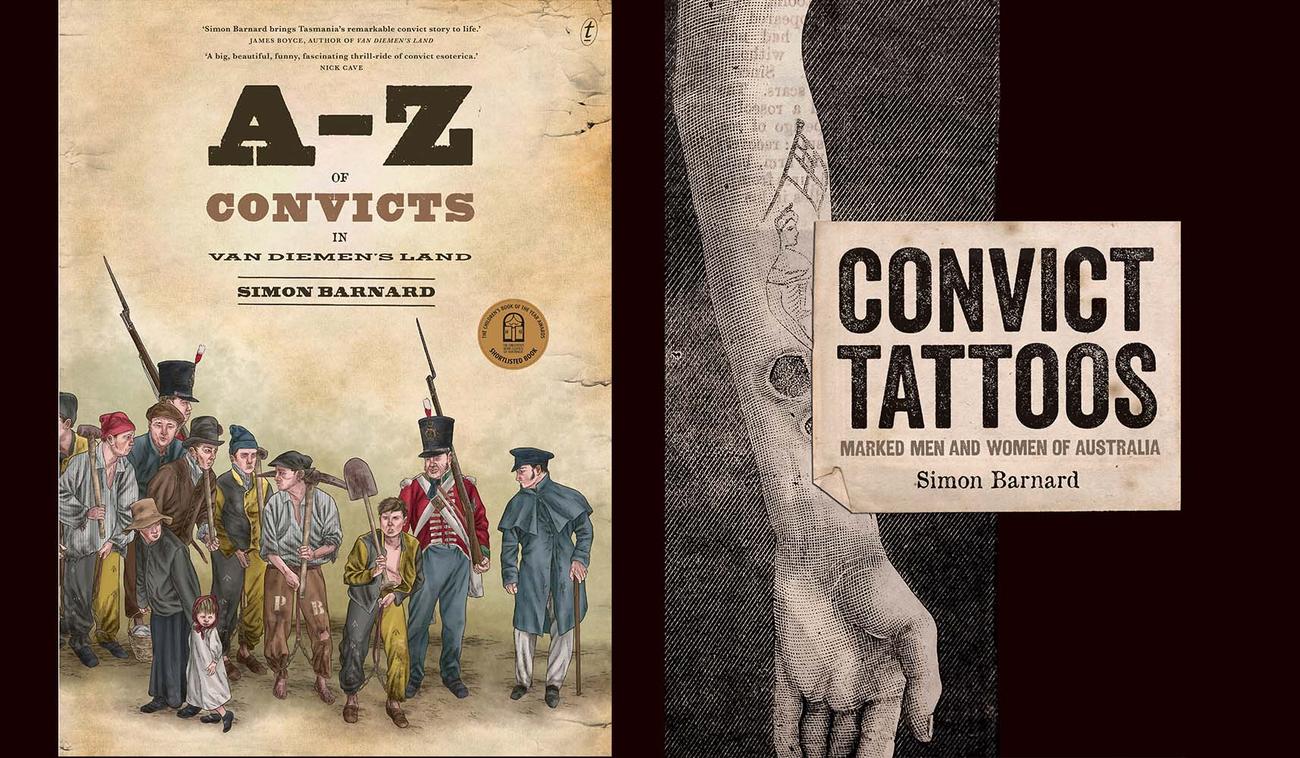

Simon Barnard, author of A–Z of Convicts in Van Diemen’s Land and the upcoming Convict Tattoos, was interviewed by Jill Fitzsimons, Learning Leader of English at Whitefriars College, and her Year 12 Whitefriars College English class.

In VCE English, many schools explore Context: Encountering Conflict and study Kate Grenville’s The Lieutenant. Students draw on the ideas and arguments The Lieutenant raises about the broad theme ‘encountering conflict’, but also use supplementary material to challenge or expand on these ideas and arguments.

To this end, we thought A–Z of Convicts in Van Diemen’s Land and Convict Tattoos would provide us with some terrific material, especially because the convicts in The Lieutenant are interesting but marginal figures.

Could we begin by asking you what types of conflict the early convicts encountered?

The first convicts battled against things you might expect, such as climate, and inadequate food and clothing, but they also fought the conflict inherent in punishment and rehabilitation, or conflict resulting from inexperience or ignorance. The first Van Diemonian absconders bolted in November 1803; they returned soon after, exhausted and starving, and were punished during colonisation celebrations.

What kinds of crimes led to transportation?

All kinds. Oddball examples include sacrilege, poisoning, selling dodgy food, vagrancy, perjury and bigamy. Dennis Collins lobbed a rock at King William and was transported for life. Petty theft was the most common crime. Maybe ask yourselves this: if you were selecting people to colonise a country, would you be more concerned with their criminal history or with their health, capabilities and skill set?

Did the convicts’ criminal ways continue once they arrived in Australia or were there cases of genuine redemption and growth?

The majority of convicts were charged with minor offences such as being ‘absent without leave’ or ‘disobedience of orders’ after their arrival, which suggests that infractions were an unavoidable part of life. A few convicts, such as William Field, prospered spectacularly but the majority settled down and simply got on with their lives.

Do you believe the conflicts the convicts encountered broke them mentally? Or do you believe they actually had some form of hope?

Some broke, sure. Robert Hesp axed another convict to death in order to bring about his own execution. James Mason lopped off two of his own fingers in an attempt to avoid work. Thomas Byrnes’ death was attributed to a ‘broken constitution’. Hope was vital. The anchor, a symbol of hope, was the most popular tattoo motif—more popular than a cross or crucifix, which suggests that hope surpassed faith.

What impact did the isolation of the colonies and the tough physical conditions and work have on the convicts?

Most convicts never saw their homeland or loved ones again, which must have taken a huge emotional toll but, physically speaking, life in Australia was better: food was more wholesome; the climate was kinder; living conditions were cleaner and less crowded.

Was being a convict as damaging to a person’s future as being an ex-criminal in today’s society? How much shame and disapproval came with being a convict?

There was a huge social divide, but convicts were encouraged to settle, to live down their criminal past respectably, and to help the colony prosper. Some convicts, like William Derrincourt, attempted to conceal their convict past. Others, like William Thompson, embraced it—Thompson even posed for photos dressed in convict gear. In the mid-nineteenth century there was a push to move on, and Van Diemen’s Land was renamed Tasmania. You might ask each other how you view ex-cons, and what you deem worthy of punishment and effective as rehabilitation. And keep in mind that a person without a criminal record is not necessarily a law-abiding citizen—they may have committed crimes and not have been caught (or prosecuted!).

What was the degree of conflict between the convicts and the indigenous people?

They waged war. Convicts, acting in the interests of colonists and the government, slaughtered many Aborigines, and suffered comparatively few fatalities. There were also Indigenous trackers who assisted in apprehending convicts, and some convicts, such as Michael Howe, may have formed Indigenous alliances in order to remain at large.

What influenced the convicts’ choice of tattoos? Was choice always involved? Could you tell us about any tattoos that symbolised defiance or even a desire for atonement?

Convict tattoos typically expressed love and reaffirmed the convicts’ sense of self. Choice was not always an option: army deserters were forcibly tattooed with the letter ‘D’. It could be argued that within the uniformed rank and file of penal life every tattoo was an expression of defiance. George Dakin’s hand was tattooed with Proverbs 14:9—‘Fools make a mock at sin’. Dakin’s tattoo may have been acquired as a form of atonement, but it might have also been a form of rebellion—the perfect foil when saluting a disdainful superior.

What were some of the relationships established between free settlers and convicts who both had to face similar hardships with life in the colonies?

There were relationships of every kind. Edward Lord, for example, built an empire bolstered by convict labour, and one of his convict servants, David Gibson, used his connections with Lord to also amass a fortune. James King wasn’t as fortunate: he was done for stealing two of Lord’s sheep and sentenced to life at Port Arthur. But Lord was no angel. He was accused of corruption, smuggling, bribery, selecting his convict wife, Maria Riseley, from a line-up of women at the Parramatta Female Factory, and one of his female servants, Ann Fry, named him the father of her illegitimate child.

Do you think Alexander Pearce was inherently evil, or just a man whose desperation drove him to extremes?

Cannibalism wasn’t uncommon. There are examples of other convicts who resorted to butchery during the 1820s. What we know of Pearce prior to his escape suggests that he was just an average Joe.

Heavy questions. Great work guys, and Jill. Thanks for your interest and support but keep in mind that it’s better to draw your own conclusions—keep questioning—keep thinking. Simon Barnard