The Devil Whooping It Up

There is a saying about the British Broadcasting Corporation that it has inspired no great novel because nobody with the talent to write one has stayed long enough to do the necessary research. The same is very nearly true of modern Wall Street, despite its apparent wealth of stories, of characters, of drama and of...well...wealth.

There does exist some pretty good stuff, chiefly satirical, written by those who have been close to the action: Bombardiers (1995) by Po Bronson (a trader at Credit Suisse First Boston); All I Could Get (2003) by Scott Lasser (a trader at Lehman Brothers); Mergers & Acquisitions (2007) by Dana Vachon (a banker at J. P. Morgan); there are the passable thrillers of Stephen Frey (ex-J. P. Morgan) and Tom Bernard (ex-Salomon Brothers); best of all, perhaps, the patrician comings and goings in the novels of Louis Auchincloss (a lawyer at Hawkins Delafield & Wood), such as The Embezzler (1966), A World of Profit (1968) and Diary of a Yuppie (1986).

Fictional characters have also long been located on Wall Street, from Charles Gray in John P. Marquand’s Point of No Return (1949) and Raymond Eaton in John O’Hara’s From the Terrace (1958) to Sherman McCoy in Tom Wolfe’s The Bonfire of the Vanities (1987) and Patrick Bateman in Bret Easton Ellis’s American Psycho (1991). But little of it would you regard as indispensable: in general, the Street has been described more vividly in journalism by John Brooks, Ken Auletta, James B. Stewart, Bryan Burrough, William D. Cohan and Roger Lowenstein; in memoir by Michael Lewis, Jeffrey Beck, Jim Cramer, Jordan Belfort, and John Rolfe and Peter Troob; and in films such as Oliver Stone’s Wall Street (1987), Norman Jewison’s Other People’s Money (1991), Ben Younger’s Boiler Room (2000) and J. C. Chandor’s Margin Call (2011).

I say ‘very nearly’ and ‘in general’, for there does exist Kate Jennings’ surprising Moral Hazard (first published in 2002); and I call it ‘surprising’ for the same reason the narrator, Cath, an Australian ‘bedrock feminist, unreconstructed left-winger’, finds her presence as a speechwriter at Niedecker Benecke, a bulge bracket firm ‘whose ethic was borrowed in equal parts from the marines, the CIA, and Las Vegas’, to be surprising.

Jennings, furthermore, did the necessary research: she filled just such a role at Merrill Lynch in the 1990s, a period remembered rather benignly but actually one in which financial volatility became curiously normalised, intermingling crises in India, Scandinavia, Mexico, Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, Russia, Brazil and Argentina with the collapses of Drexel Burnham Lambert, Kidder Peabody, Baring Brothers and Long-Term Capital Management, and preluding 2001’s dotcom Götterdämmerung, to the extent that the soothing notion of the market’s self-stabilising properties embedded itself in the title of Jonathan Franzen’s famous fin de siècle family saga, The Corrections (2001): ‘The correction, when it finally came, was not an overnight bursting of a bubble but a much more gentle letdown, a year-long leakage of value from key financial markets…’

Yet, in its fine disgust and moral purpose, Jennings’ work has less in common with the aforementioned titles than with an earlier period of writing about financial markets, around Theodore Dreiser’s The Financier (1912) and The Titan (1914), Upton Sinclair’s The Moneychangers (1908), Frank Norris’s The Pit (1903) and David Graham Phillips’ The Deluge (1905), which describe the days—before the Federal Reserve, before Standard Oil Co. of New Jersey v. United States, and long before the Securities and Exchange Commission—when finance was perhaps even more lawless than it is now, and the public arguably even greater dupes.

‘Financiers do not gamble,’ says Phillips’ chief protagonist in The Deluge. ‘Their only vice is grand larceny.’ Cath’s friend Mike, a wry risk manager, updates such parsing: ‘Tobacco companies are immoral. Children are amoral. Bankers are feckless.’ But when Cath herself pauses to consider the quotidian reality of corporate life, it is in unashamedly political terms.

The United States is a democracy, and yet it’s powered by autocratic corporations. Its engines are fascist. Nothing democratic about them. Paradoxical, wouldn’t you say?…

There’s a pretense at democracy. Blather about consensus and empowering employees with opinion surveys and minority networks. But it’s a sop. Bogus as costume jewelry. The decisions have already been made. Everything’s hush-hush, on a need-to-know-only basis. Compartmentalized. Paper shredders, e-mail monitoring, taping phone conversations, dossiers. Misinformation, disinformation. Rewriting history. The apparatus of fascism. It’s the kind of environment that can only foster extreme caution. Only breed base behavior. You know, if I had one word to describe corporate life, it would be ‘craven’. Unhappy word…

Corporations are like fortressed city-states. Or occupied territories. Remember The Sorrow and the Pity? Nazi-occupied France, the Vichy government. Remember the way people rationalized their behavior, cheering Pétain at the beginning and then cheering de Gaulle at the end? In corporations, there are out-and-out collaborators. Opportunists. Born that way. But most of the employees are like the French in the forties. Fearful. Attentiste. Waiting to see what happens. Hunkering down. Turning a blind eye…

American corporations. Invented to provide goods and services, but that’s the least of it now. Which brings me to globalization. Better not get me started.

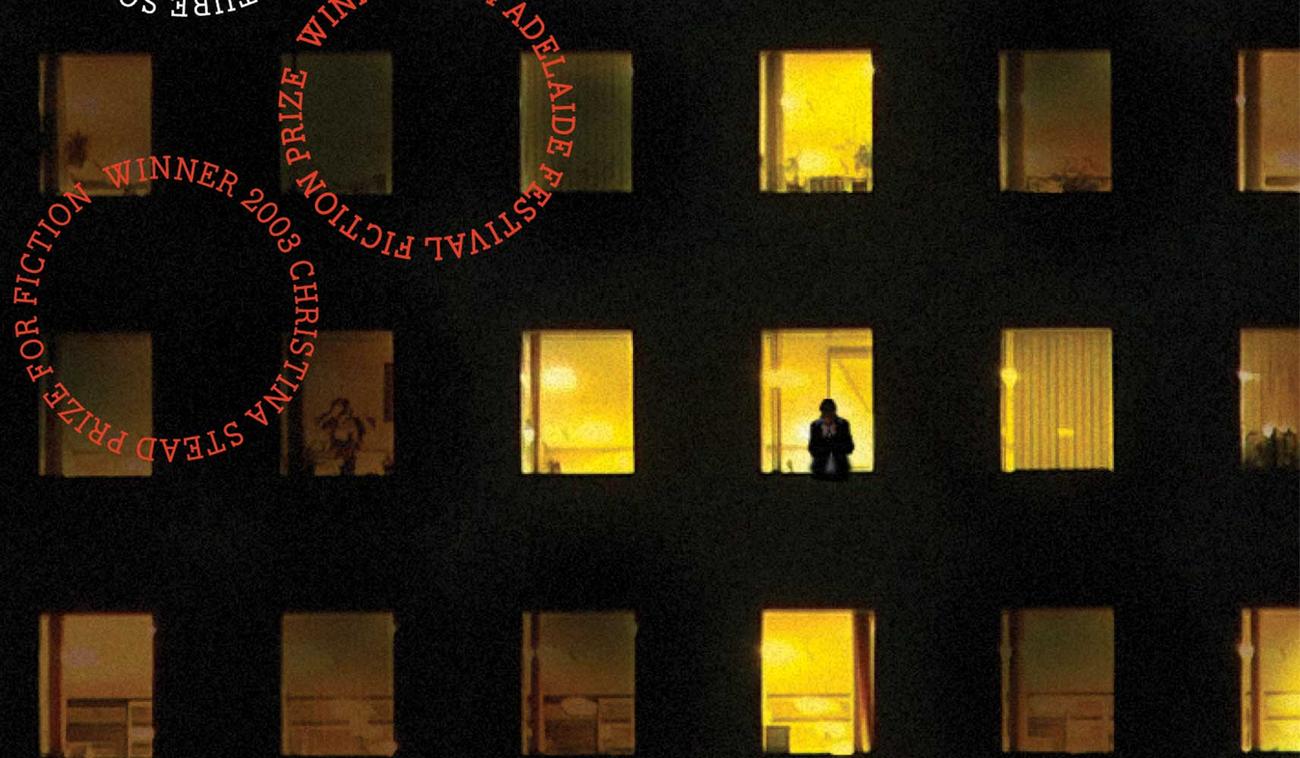

What gives this monologue additional impact is its addressee: Cath is thinking aloud in the presence of her much older partner, Bailey, who because his faculties have been ravaged by dementia can understand not a word. And Bailey—once cheerful, warm, gregarious; now anguished, ‘becoming formless and vague’, requiring constant oversight—is the reason that Cath must keep such thoughts to herself at Niedecker Benecke: as do we all, she needs the money to keep body and soul together. ‘I was commuting,’ she reflects, ‘between two forms of dementia, two circles of hell. Neither point nor meaning to Alzheimer’s, nor to corporate life, unless you counted the creation of shareholder value.’

Only with Mike, with whom Cath shares a youth of student radicalism and an adulthood of socially disapproved smoking, is any degree of candour possible, and she collects his obiter dicta about the inherent instability of a market leveraged to the hilt. (‘The only perfect hedge is in a Japanese garden’; ‘They think they’ve beaten the odds, vanquished them. But these systems are never infallible. At some point, they always blow up.’) With her memorably described superiors, Hanny (whose skin ‘patched with perspiration at the slightest exertion’), Bart (who ‘feigned aggression like a barracuda’), Chuck (who ‘lived to please, loved to schmooze’) and above all Horace (‘wreathed with gossip, like mist on a mountain’), she must be more guarded. ‘Nearly everyone at Neidecker claimed to be above the fray, going along with absurdities of corporate life, while laughing up their sleeves,’ she observes. ‘Yet they guarded their positions on the food chain with the single-mindedness, the savagery, of wolves.’

The impossibility of speaking out is glimpsed at a corporate conference following the Russian default, when a colleague asks the obvious question of the CEO:

Why was so much of our capital invested in a country that has never had a market economy, never had the civil institutions that make a market economy possible? Not only that, a country run by gangsters. This is not a secret. Anyone who reads the New York Times knows it.

Cath knows enough of corporate protocol to understand: ‘The banker who asked the question was dead.’ But she has already inadvertently killed her closest friend at the firm, by previously blurting to Horace what Mike had told her of the frailty of a now-collapsing hedge fund in which the firm was invested. Mike loses his job, without rancour: ‘They would have fired me, anyway.’ Cath resigns hers when it’s no longer needed, without regret: ‘I hated every moment while I was there, but I’m not sorry for the experience.’

For Horace, they understand, it’s nothing personal; it’s just that ideology can brook no argument. ‘Mike and I, flotsam from the sixties, weren’t the idealists, not by any stretch; he was. Horace idealized unfettered markets, which he genuinely believed had the power to create a brave new world.’ At last, she learns second-hand that he, too, has been defenestrated, and Neidecker Benecke sold.

So, while Moral Hazard is a fine Wall Street novel, it is also more, enunciating as it does disquieting truths about a services economy. Cath is vulnerable, Bailey more so. The superior outlook from Cath’s workplace does not obscure its realities:

I had gained a whole different view of New York’s skyscrapers. I looked at them and didn’t see architecture. I saw infestations of middle managers, tortuous chains of command, stupor-inducing meetings, ever-widening gyres of e-mail. I saw people scratching up dust like chickens and calling it work. I saw the devil whooping it up.

To make good her escape, she needs her dearest love to die. Moral hazard, indeed.

Modern working life is replete with unpalatable compromises and perverse incentives. The investment banker-turned-anthropologist Karen Ho concludes in her fascinating ethnography Liquidated (2009) that Wall Street has pioneered a whole way of work—involving short time horizons, constant job insecurity, minimal institutional loyalty, parrot cries of ‘shareholder value’ and ‘creative destruction’—and mandated it for the rest of the world. In one of my favourite books about modern offices, Joshua Ferris’s Then We Came to the End (2007), a character wanders quietly back and forth, all the while composing ‘a short, angry book about work’. Moral Hazard is how that book might read.

GIDEON HAIGH is an independent journalist who lives in Melbourne. He is the author of more than thirty books, including Bad Company: The Strange Cult of the CEO, The Office: A Hardworking History and, most recently, Certain Admissions: A Beach, a Body and a Lifetime of Secrets.

Moral Hazard will be released on Wednesday 23 September as a Text Classic. Pre-order from your favourite bookshop or online.

And check out our full Text Classics range here.