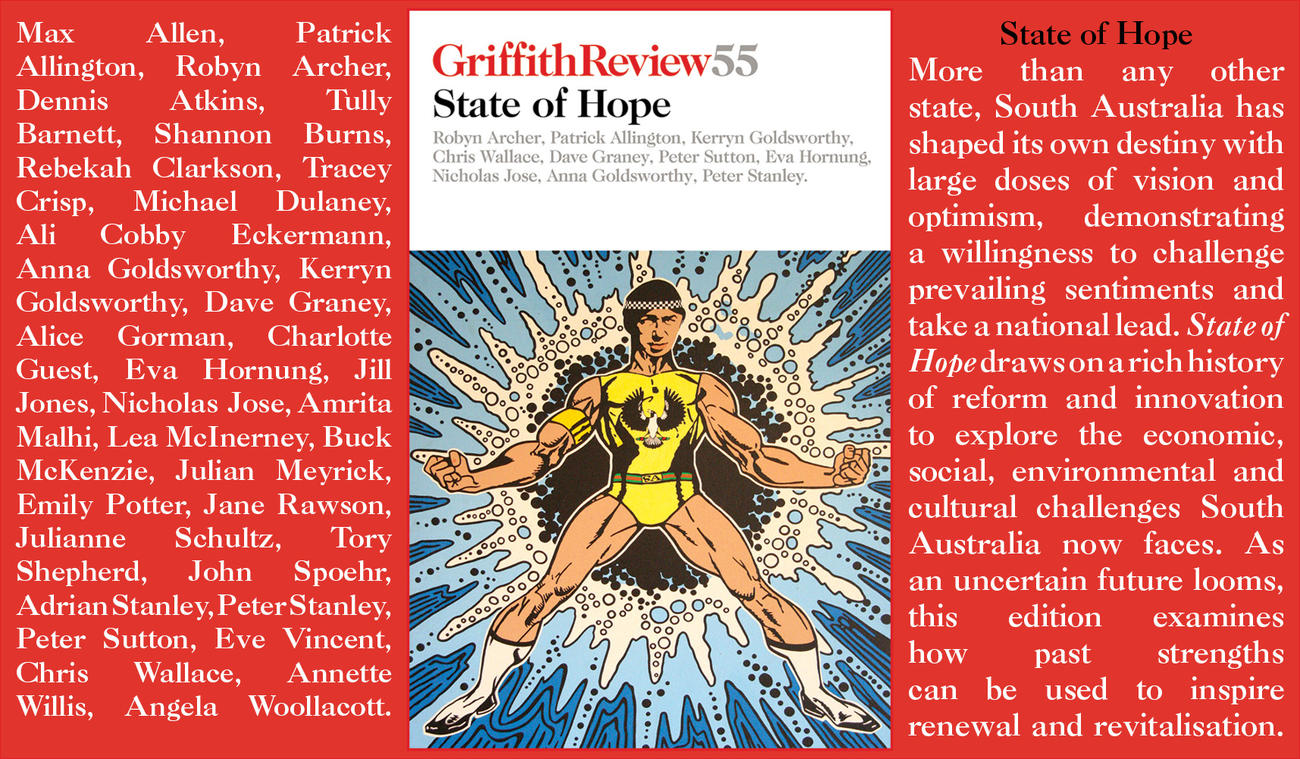

This quarter’s Griffith Review55: State of Hope focuses on South Australia and features a weighty rollcall of writers such as: Patrick Allington, Robyn Archer, Eva Hornung, Dave Graney, Kerryn Goldsworthy and Peter Stanley.

Since 2003, Griffith Review has been the leading literary magazine in Australia, with an uncanny ability to anticipate emerging trends. Each themed quarterly collection presents fresh insights and analysis of the big issues from pre-eminent Australian and international writers. GR features essays, reportage, memoir, fiction, poetry and artwork from established and emerging writers and artists.

Fresh from GR55: State of Hope here is a timely essay in this world of alternate facts and post-truth, Into the Dark: What happens when ‘truthiness’ eclipses truth by Tory Shepherd.

Tory Shepherd is political editor and senior columnist for The Advertiser, where she contributes two weekly columns: one on Canberra’s spin, and a second on the other ways in which bullshit infiltrates our world.

In the Dark: When ‘truthiness’ eclipses the truth

A CELEBRITY CHEF declares dairy causes osteoporosis, and cholesterol medication is bad. Parents shy away from giving their children life-saving vaccinations. People are stringing crystals around their neck, then necking kale juice on the way to the chiropractors to have their neck cricks cracked.

‘Truthiness’—where made-up information parades as fact—too often trounces truth. Thanks to Web 2.0, we are swamped by information. And many people are unable to sift out the misinformation. Some start to fear science and all it has produced. The anti-vaxxers and those who reject modern medicine join tribes online and in the real world and reinforce each other’s beliefs. Climate deniers snuggle down in their comfortable little belief cocoons, rejecting evidence and rational thought.

There are many reasons bullshit is dangerous. It is also regressive. It may seem super-modern to embrace television chef Pete Evans’ idea that calcium from dairy mysteriously leaches the calcium from bones, but in truth most of his advice has more in common with pre-Enlightenment thinking. Progress and growth—two things desperately needed in South Australia—depend on knowledge, science, technology, medicine. Facts.

A specific area where facts are often ignored in favour of truthiness is climate change. The phenomenon of climate-change denialism shows no sign of being beaten down by ever-increasing evidence that the climate is in the process of change and human activity is to blame. And denialism has a new champion in the federal parliament—One Nation Senator Malcolm Roberts says all the world’s scientific organisations are corrupt and climate change is bunkum. At the same time, there is an enduring scepticism towards renewable energy and its role in reducing emissions.

When the lights went out in South Australia in September last year, the state was plunged into real and metaphorical darkness. The ‘black system’ event was unexpected and shocking, but while families were still searching for their candles and torches, politicians had already started blaming the state’s reliance on wind power.

Deputy Prime Minister Barnaby Joyce said South Australia relied too much on renewables. ‘[Windpower] wasn’t working too well last night, because they had a blackout,’ he told the ABC. South Australian Senator Nick Xenophon quickly blamed the ‘reckless’ transition to renewable energy. ‘We have relied too much on wind,’ he said. Energy Minister Josh Frydenberg and Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull steered away from directly blaming renewables, but cynically used the situation to say there were ‘questions to be asked’ about South Australia’s power mix. At that early stage, no one could shine any light on the cause. It may be that more information emerged to implicate wind power directly. But what is clear is that certain people were in an unseemly haste to blame the turbines.

So, all of a sudden, South Australia was at the centre of a tussle over renewables and action on climate change. Just when the state is leading the pack on renewables, and when it is in dire need of new industries and new jobs, the path ahead became decidedly less clear. The federal government took aim at ‘aggressive’ renewables targets, signalling they are not about to swing more support behind them.

At the time of writing, the Australian Energy Market Operator’s advice was that wind farms were involved, but only in an incidental way; they were designed to shut down when the system went wonky and that shutdown triggered a big draw on the interconnector to Victoria, which then crashed the system. However, neither climate change deniers nor politicians want the facts to get in the way of a good story. That is eternally true of politics. But why do people with no clear vested interests hold false beliefs in the face of contradictory evidence?

MOST PEOPLE BELIEVE some non-scientific things. Some of those beliefs can be harmless. The danger comes when people bunker down on potentially harmful beliefs and reject any contradictory evidence. Their brains ossify. They stop learning and reject the scientific evidence.

When we were primitive beings we found meaning in star patterns, in forked lightning, in the entrails of goats. Now we know how to fly to the stars and we’ve started to understand how to use them to understand how the universe was formed. We use science to predict and tackle bushfires sparked by lightning, and to tell us how to sous-vide a goat; we use data to predict the future.

We may have progressed as a society, but there is still far too much backwards thinking. Michael Shermer, who wrote Why People Believe Weird Things (Henry Holt, 1997), writes in The Believing Brain (Henry Holt, 2011) that Homo sapiens believe things for a complicated and sometimes random series of reasons. Why they hold on to the wrong beliefs is the interesting question—why, when presented with evidence of climate change or the benefits of renewable energy, do some refuse to accept the facts?

Shermer refers to the TV series The X-Files. Credulous FBI agent Fox Mulder has a poster in his office that reads ‘I Want To Believe’. Humans want to believe, in part, because we have evolved to be pattern finders. To find the evidence. Those who could track the droppings of prey or spot the telltale signs of a predator were more likely to survive. Finding patterns in stars might help you find the way home.

Shermer points to how this operates for conspiracy theorists (those who believe man never landed on the moon, or that September 11 was a grand hoax) when he writes in The Believing Brain: ‘It is because their pattern-detection filters are wide open, thereby letting in any and all patterns as real, with little to no screening of potential false patterns. Conspiracy theorists connect the dots of random events into meaningful patterns, and then infuse those patterns with intentional agency.’

There are elements of conspiratorial thinking and ‘intentional agency’ in all anti-science theories: vaccinations cause autism, but the vested interests in the medical establishment are covering it up; putting fluoride in water is not about dental health but a way for the government to control the populace; climate change is an invention of scientists desperate to maintain their government funding. With so much data involved it’s easy for deniers to find their own patterns, their own ‘proofs’ of the great conspiracy.

Where Shermer seeks to understand, Bernard Keane and Helen Razer are scathingly dismissive. In A Short History of Stupid (Allen & Unwin, 2014) they argue that facts have been eclipsed by opinion, a common hypothesis when people talk about how the media has become dominated by ‘feelpinions’ and shock jocks: ‘Facts do not matter. And this is bad enough in itself. But it is not just that we feel entitled to our opinion, as nearly everybody does. We are obliged to have an opinion… An opinion is empowering. An opinion is a sign of high self-esteem,’ they write. ‘Facts, in fact, have become a sort of optional extra.’

It does sometimes seem hopeless to argue in favour of science when so many seem to see it as an ‘optional extra’. Humans have an astounding ability to jerry-rig their own brains, shoehorning in the stuff that concurs with pre-existing beliefs, yet blocking out anything that might disrupt those beliefs. And there’s the internet as a friend and a bulwark. It is possible to Google in such a way that each search reaffirms already established points of view. Facebook or Twitter can be curated so you only hear from those you already agree with. The web can be used in order to cement confirmation bias and shut out dissent. Online, no one can hear you screen.

SOME ARGUE THAT truth is relative. Climate change deniers claim their (cherry-picked, wrongly interpreted) data is more valid than NASA’s, say, or the Bureau of Meteorology’s. Still others state science is a set of beliefs with no more claim to truthfulness than a religion. And having a different belief to the mainstream makes people feel special. They’re not just ‘sheeple’, unwitting believers in what the authorities say, but are part of a special subsection of society that possesses the truth. Like an intellectual secret handshake, they learn the language and attributes of their new society. David Aaronovitch, in Voodoo Histories: The Role of the Conspiracy Theory in Shaping Modern History (Jonathan Cape, 2009), writes that pseudoscientists (specifically pseudoscholars):

‘[Understand] what everybody else doesn’t, what everybody else would most like to deny. They are the lonely custodians of the truth and they got there through the quality of their minds—and by being brave enough to read a book.’

They see themselves as warriors.

Let’s go back to chef Pete Evans again. He, and his hordes of followers, think he has just as much right to give medical advice as, say, someone who is medically trained. They’re picking this misguided sense of ‘my opinion is worth as much as yours’ over actual truth. Truthiness trumping truth again. Another example is when, in October last year, Senator Roberts clashed with Australia’s Chief Scientist Alan Finkel over climate change; Roberts is certain he knows better than our top expert.

Online, deniers and conspiracy theorists strengthen their bonds with others who believe the same misinformation as they do. The mistrust of the ‘establishment’, of the accepted science, too easily turns to loathing. This is where the divide between science and anti-science really kicks in. The conspiracy theorists loathe the system, and the system starts to loathe them in return. Pseudoscientific beliefs are consistently debunked by scientific institutions such as the Australian Medical Association, the CSIRO, the Cancer Council, NASA. But those who feel they are treated with contempt are unlikely to change their minds; they only harden against the ‘authorities’ that dismiss their strongly held thoughts.

Meanwhile, this anti-science tendency is getting traction outside the conspiracy theorists purview. It’s creeping into our political system. Note how the government keeps saying we have to ‘respect’ One Nation and their voters—the voters who think climate change is a fabrication, that Muslims are to blame for their kids not being able to get jobs, and that the Family Court system is to blame for men bashing and killing women. Some in parliament already professed these beliefs. Now others with similar attitudes have the heft of the balance of power in the Senate, and therefore the power to shift policy.

Aaronovitch again: ‘The belief in conspiracy theories is…harmful in itself. It distorts our view of history and therefore of the present, and—if widespread enough—leads to disastrous decisions.’ There are myriad very good reasons society grants everyone their own facts. Voters, obviously, influence parliament and politics, and therefore policy. If that influence is not fact based, there is more likelihood of public funds being directed to ineffectual programs. A smaller chance of taxpayer dollars going to mitigate climate change, to encourage vaccination, or to astronomy rather than astrology.

The believing brain skitters over contradictory evidence; debunking bunkum is easy on paper, but it’s nigh impossible to convince someone who has convinced themselves that they are right. In The Debunking Handbook (University of Queensland, 2011), John Cook and Stephan Lewandowsky warn that it is far too easy to reinforce a myth. ‘Mud sticks,’ they say. You can go all out talking about why people who believe climate change isn’t happening are wrong, you can back it up with rock-solid facts, and people will still take away the message that ‘climate change isn’t happening’.

Even as the Australian Energy Market Operator insisted there was no evidence that the intermittent nature of wind-generated power was the reason South Australia went black, people kept targeting wind farms. They heard only what they wanted to hear.

In response to conspiracy theorists, pseudoscientists, shysters and fraudsters, there is a grand temptation to smack them down. The ‘smackdown’ has become a beguiling thing celebrated by some aspects of the media. ‘Boom,’ they say. ‘Watch this scientist take down Malcolm Roberts!’ It’s a misplaced optimism, this idea that by ‘nailing it’ with some pithy words on The Project or Q&A, suddenly people will wake up to their false beliefs.

If people already believe in her, they won’t suddenly see Senator Pauline Hanson as the fact-free bastion of bitterness that she is. Rather, they’ll see a smug media gloating about the treatment of someone they admire. By this stage they’ve committed themselves to their beliefs. The smackdown is just a smack in the face, and will earn no converts. Throwing facts at people doesn’t change their minds; it might even drive them deeper into their little belief cocoon.

SLOPPY, ANTI-SCIENTIFIC THINKING leads to poor policy, stagnation and deaths. Climate change denialism and resistance to renewables means that at a federal level Australia is not doing all it can; the manufactured ‘controversies’ put the brakes on progress.

The rejection of well-proven science can be fatal. That has been shown in those who reject vaccination, or conventional cancer therapy. If the world does not speed up its action on climate change more people will die through the increasing volatility of the weather.

Truth, arrived at through the scientific process, leads to progress and growth. South Australia, particularly, is in need of a rather large growth spurt. Our employment levels are languishing. The economy is worse than sluggish. Our dwindling share of the nation’s population means we are set to lose one of our federal seats in parliament, leaving us with just ten MPs in the House of Representatives of one hundred and fifty seats.

Science is a beacon of light in the quagmire. South Australia has the beginnings of a way to finally ditch the ‘City of Churches’ tag and become the centre of rational thought and progress. Of wind farms and solar power and peerless thinkers and cutting-edge technologies. World-class medical facilities and top-notch researchers. Science can make our wine and cheese even better. It can open up new avenues of industry and create jobs.

South Australia has a proud history of progressive thinking, and the next leap is well overdue. The settings are ostensibly in place; Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull talks endlessly about investing in innovation. Our very own Christopher Pyne, as defence industries minister, will focus on ensuring the government’s enormous investment in submarines and ships has a full flow-on benefit throughout the state. The blackout-induced attack on renewables is a step backwards—hopefully the only one.

Our state government has consistently backed renewables, has invested in the new Royal Adelaide Hospital, and has created the magnificent South Australian Health and Medical Research Institute to attract the world’s best minds.

Perth’s mining boom has finished booming. Sydney’s glitter is glistering, Melbourne’s bubble is popping. Adelaide has the glimmer of a new beginning. We have to convince the next generation—and the one after that, and the one after that—to reject anti-science. South Australia must become a state that thoroughly and unashamedly embraces rationality and progress.

If there’s one little acronym everyone uses to discuss the state’s future, it’s STEM. Science, technology, engineering and maths. All of which rely on truth and the rejection of truthiness to succeed. Our new jobs will be in renewables, as well as advanced manufacturing, submarines and ships, medicine—avenues of research we don’t even know about yet. Wind turbines and solar. Then the nuclear industry, maybe.

We already have the intellectual infrastructure to lead thinking on this. We have always combined our prestigious arts festivals with academic adventures in the traditional and the social sciences. In 1897, Mark Twain wrote of Adelaide in Following the Equator:

‘You see how healthy the religious atmosphere is. Anything can live in it. Agnostics, Atheists, Freethinkers, Infidels, Mormons, Pagans, Indefinites: They are all there. And all the big sects of the world can do more than merely live in it: they can spread, flourish, prosper.’

What should spread, flourish and prosper here now is rational, scientific thought. An antidote to the world’s woo woo.

Once upon a time, a University of Adelaide academic, Professor Frank Fenner, was instrumental in virus control. He halted the spread of the rabbit-killing myxoma virus. He also drove the eradication of the smallpox. One guy, from little old Adelaide, stopping the viral spread.

South Australia needs a vision for the future. A vision for jobs and growth, sure, but also a more soaring mission. All the optics point to science, medicine, technology.

The late Carl Sagan was one of the best the world has seen at promoting rational thought. He wrote inThe Demon-Haunted World: Science As A Candle In The Dark (Ballantine Books, 1997):

‘We’ve arranged a global civilisation in which most crucial elements profoundly depend on science and technology. We have also arranged things so that almost no one understands science and technology. This is a prescription for disaster.’

Either the politicians have to lead the way, or voter sentiment must shift and force them to stick to the scientific path, to recognise the might of climate change and the power of renewables.

Facts and science are the way out of the demon-haunts. Stopping the viral spread of truthiness and steering the boat back to truth. That’s South Australia’s hope and its candle in the dark.