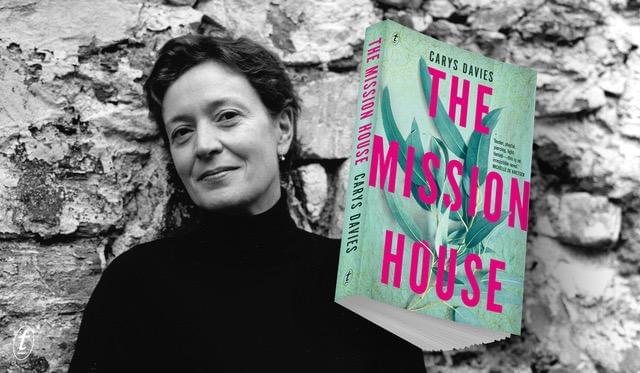

Carys Davies’s The Mission House boldly and imaginatively interrogates the fractures between faith and non-belief, young and old, imperial past and nationalistic present. Tenderly subversive and meticulously crafted, it is a deeply human story of the wonders and terrors of connection in a modern world.

Carys answered some questions about her inspirations, her time in India and her penchant for dramatic endings.

When did you come up with the idea to write The Mission House? What was your inspiration?

The writing of The Mission House goes back ten years, to 2011, when I was helping out at an orphanage in Ooty, a former British hill station in the Nilgiri mountains of southern India. I was so struck by the particular strangeness of being British in an old colonial town and being surrounded by relics of British rule. So much of it – the institutions, many of the buildings, the speaking of English – was familiar, and yet at the same time I felt utterly foreign; there was so much about the place and the culture I didn’t know or understand. In the years that followed, I wrote a lot about that experience without having any clear sense that I was beginning a novel. Slowly though, the figure of my anti-hero, Hilary Byrd, began to emerge: a troubled, introspective fifty-something Englishman who seeks refuge in a place rather like Ooty, only to find himself struggling to read his unfamiliar surroundings, and the feelings of the people who take him under their wing.

Tell us about your time in India – where did you go; how much in-situ research did you do?

Like Byrd, I travelled between the cities of the plains, and along the coast south of Chennai, on the Bay of Bengal. But mostly, like him, I was living in the Nilgiri mountains of Tamil Nadu in a former British hill station. I kept a diary the whole time, because it seemed possible that I might write about the place in some way, and real, concrete details are always very important in my writing. Byrd’s bungalow, for example — the mission house of the title — is itself modelled very closely on the one I lived in, and when Byrd is in there, pottering about and cooking for himself and worrying about his life and the possibility that he might have fallen in love, I can see every inch of it. Likewise, the presbytery garden and the long, puddled driveway that leads to it from the road. The same goes for the places he visits — the Botanical Gardens and the lake, the Assembly Rooms and the chocolate shop, the market and Modern Stores.

What can The Mission House tell us about the times we are living in?

None of us knows yet how thoroughly this pandemic and the Black Lives Matter movement will, between them, remake the world. But the signs are that they will have a massive impact on the way we live our lives. What worries me is that populist nationalism will be the first line of defence for those who feel threatened by this re-making, and while I haven’t set out in The Mission House to unpick that, the book has important things to say about the necessity of knowledge, and how, without it, none of us can begin to understand the lives of others: we can’t talk about what we don’t know. It has a lot to say, too — at a time when many of the people ‘in charge’ are behaving badly, and lying about what they have and haven’t done — about moral responsibility, and being our best selves in a world gone wrong.

Your endings are always dramatic. Do you plan it that way before you start writing, or do you feel your way through as you are writing?

I don’t think I could write a novel, or a short story, if I knew what the ending was going to be. Finding the ending is, for me, almost the whole point, because it’s such a huge part of what everything that’s come before it has been about, and I am always feeling my way towards that. I begin with a circumstance — in this case Byrd arriving, alone, at the mission house, with his uneasy blend of guilt and fear, suspicion and ignorance. Once I have that circumstance, I see where it takes me. In The Mission House it took a long time for the other characters to come into focus and for me to understand how their lives would affect Byrd’s, and how he would affect theirs. Working this way, slowly and without forcing anything, I know when I’m getting close to ‘the end’. How that unfolds, when I eventually get there, feels as surprising and inevitable to me as I hope it does to the reader.