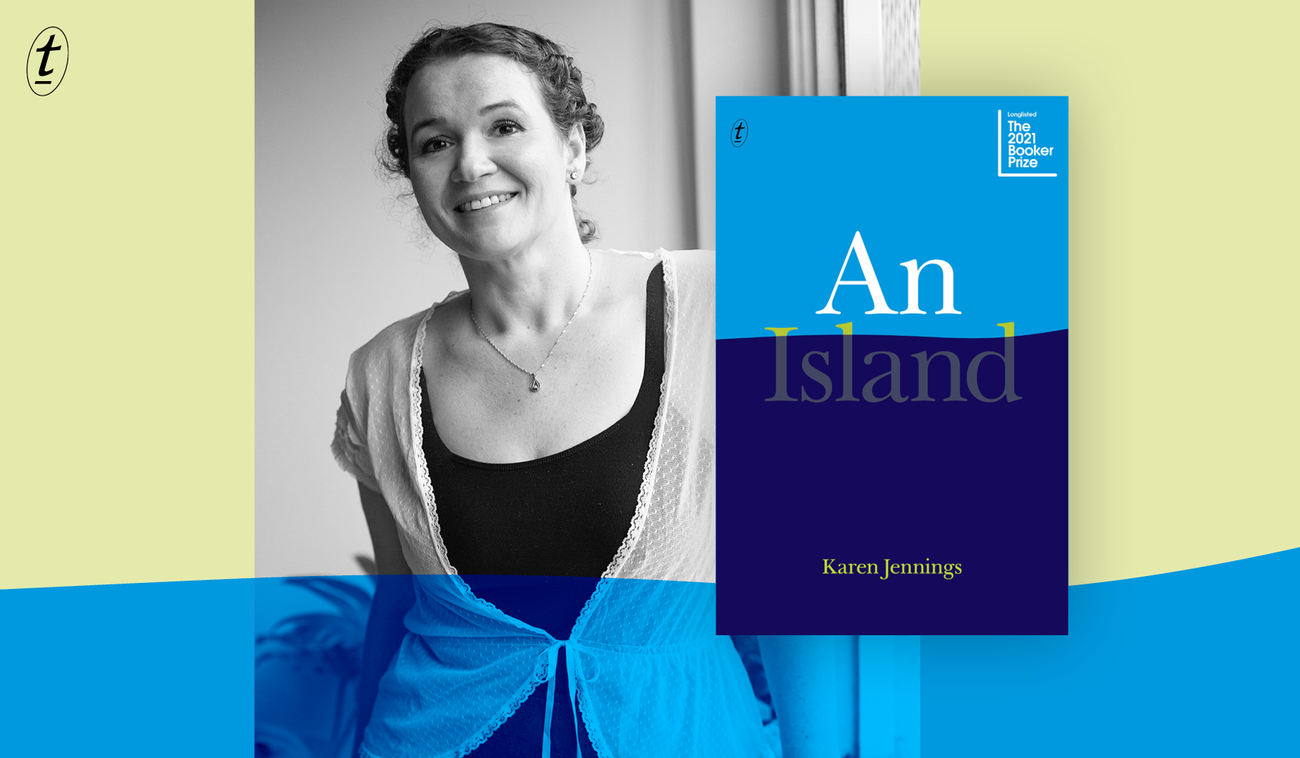

Michael Heyward, publisher at Text, interviewed Karen Jennings, the Booker-longlisted author of An Island.

You were born in Cape Town and your parents were both teachers. Your mother is Afrikaans and your father English. Did you have a bookish childhood? Did you grow up with both languages?

I started speaking quite late – my mother even took me to a specialist to see if I was okay. But when I did start speaking it was in both languages and in full sentences. We had a rule in our family – we spoke English to my dad and Afrikaans to my mom. As for the books – yes, it was a very bookish childhood. My favourite book as a small child was 1066 and All That: A Memorable History of England, by W.C. Sellar and R.J. Yeatman. It is a humorous history of England written in the 1920s, serialised in Punch and first published as a whole in 1930. Clearly not the normal type of book that a five-year-old would ask her dad to read to her! I still have that copy. But, of course, there were the usual picture books too. My choices weren’t all odd.

You started writing as a child. When did you start to believe that writing was your vocation?

It is hard to say. I can’t pinpoint an exact moment. I suppose it happened incrementally. I knew that I wanted to write, but I don’t know that I put much thought into the idea of having a calling. It was just part of me and that was that. I do remember writing a poem at the age of about six or so, about water from the irrigation system dripping in the garden. I remember being thrilled by the feeling of writing and then of having written. I even typed it up on the family typewriter afterwards!

You were a child when the apartheid era came to an end. What was that experience like?

I talk about this quite a bit with my husband – he is Brazilian and so he has questions about what it was like growing up in South Africa. I remember things that were so ordinary then, but which are shocking in retrospect. Pre-1994, we used to get the police coming to school often to give talks about how to identify bombs. Can you imagine that – six years old and knowing what different kinds of homemade explosive devices might look like. We also used to have to do special drills at school – hide under our desks in case of attacks. There is one moment that I remember distinctly. It was 1990 and I was seven. A boy at school said to me, ‘Nelson Mandela is a murderer and he is being let out of jail and he is coming to kill you.’ That night at supper I said, ‘I hate Nelson Mandela’ without having any idea of who he was other than a man that this boy had said was coming to kill me. My parents were outraged and gave me a very long lecture. I remember feeling terrible shame and going to bed to cry.

Then, fast forward to 1994, and it was like a festival at our school. We made special commemorative T-shirts, our headmistress wrote a song that we all sang with great enthusiasm – it was about peace and love. The whole atmosphere was that of something incredibly special and wonderful happening. So wonderful, in fact, that it seemed to my eleven-year-old mind like something that would only happen far away, not in our neighbourhood, and so I couldn’t understand that there were signs up at the Magistrate’s Court, which was around the corner from our school, that voting would take place there. I couldn’t fathom that ordinary people in our ordinary neighbourhood would be participating in this magical event. I really didn’t understand much of it, as you can tell.

You have talked about your love of Zola and Dickens, as well as John Steinbeck. What do you admire about these writers, and what have you learned from them?

The thing that appeals to me about these authors is that they write about the everyday, the ordinary, the forgotten people. These stories hold up a mirror to our faces.

You are also a fan of Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Ovid is a compulsive storyteller who nonetheless understands the art of concision. What do you love about him?

Oh, Ovid is excellent! His stories of transformation appeal to me on a number of levels. While they are mythical, there is so much to be gleaned from them about significant, transformative moments in our own lives. The story of Echo falling in love with Narcissus and wasting away until only the echo of her voice remains…who among us has not loved and pined and felt ourselves disappearing with heartache?

Are you a fan of Catullus too? Do you have a favourite poem by him?

I very much am a fan of Catullus. There are several poems of his that I really appreciate. I suppose the most obvious would be No. 85 – his Odi et amo, but then there are his humorous poems too. No. 69 always makes me laugh – when he tells Rufus that his armpits smell like goat! But I think the most impactful of his poems is also his longest and it is quite odd, but really a masterpiece: No. 64. In one sense it is about the way in which women have been abandoned and scorned by great men.

Which other writers are important to you? You have studied the fiction of JM Coetzee, for instance. Did his work make a difference to your development?

I wrote my MA in English Literature on women in Coetzee’s novels. I had only read Foe before choosing the topic as I had very recently made a decision to move from the Classics department to the English department and didn’t really know what to write about. At the time there was a great deal of interest in Coetzee and several other postgrads were also writing about him. My advice to anyone doing an MA or PhD in literature is not to write about an author that you like. It absolutely ruined Coetzee for me. I haven’t been able to read anything by him since then and that was almost fifteen years ago!

You also write poetry. Does poetry ask things of you that fiction can't?

Writing good prose is a challenge. Writing good poetry is an even greater challenge. To be able to render something immense and meaningful in a few words is not something that comes easily and I certainly do not consider myself a poet. I would like to go hide in a cabin somewhere and do nothing but read poetry for a year and see what effect that will have on the way in which I think and use words.

You have said that An Island began in a dream. Could you tell us a little bit about that?

I was at a writer’s residency in Denmark in August 2015 and had just finished a draft of my novel Upturned Earth. At the time there was a lot in the news about the Syrian refugee crisis – negative, xenophobic responses as well as those of sympathy and support. At the same time there were boatloads of African refugees drowning and no one said a word. It made me think about attitudes towards African refugees within Africa itself and of terrible xenophobic attacks in the continent’s history, including in South Africa. I wondered what drives feelings of xenophobia and hatred and violence. I then dozed off in my bed at this residency – in what had previously been a sanatorium – and had a vision of an island with a lighthouse on it and an old, African man frowning and alone. I sat up at once and said, ‘That’s my next book.’

Did the stranger enter the story at the same time as Samuel or did he come later?

He wasn’t in the vision I had during my nap, but he came very soon afterwards.

How long did it take you to write An Island?

It took almost exactly a year. I was fortunate enough to have been granted a Miles Morland scholarship (the Miles Morland Foundation funds a number of African authors every year) and the time period was twelve months. As it turned out, the novel was short and I also worked in a very disciplined manner, so I was able to rewrite it several times during that time.

You finished An Island in 2017 but struggled to find a publisher. Why do you think this novel was so difficult to publish?

I can only repeat what I was told by those who rejected it: it was too experimental, too African, not African enough, too short, and it wouldn’t make any money.

Colonial occupation, revolution and independence have all brought Samuel suffering. He has acted in good and bad faith. At different times we feel sympathy mixed with contempt for him. He has witnessed the effects of violence and xenophobia but he feels the same urges in himself. He is a kind of emblematic figure but he is also himself and not anybody else. One of the great things about your book is that a man who is otherwise ordinary is so fully imagined. His memories are wonderfully alive. How did you go about shaping his character and his life story?

It is honestly hard for me to remember with any sort of detail. I know that I jotted down many ideas and I wrote moments of his life onto bits of paper and tried to puzzle them together on my mother’s dining-room table. I remember it feeling like an impossible task.

Your two main characters speak different languages, and struggle to understand each other, but they are confined in the same small place. Did this bring particular problems or conversely a particular intensity to the writing?

It was necessary, very necessary, but created many difficulties. Writing a story where almost nothing happens and there is not even the relief of conversation – it was problematic to say the least!

You are white and your characters in An Island are black. You are female and your main characters are male. Do you worry that you might be telling stories that are not yours, or is it the responsibility of the writer to try to see through the eyes of others?

This was something that concerned me greatly and still does. I imagine that there will be people who are angered and unhappy and will (possibly justifiably) accuse me of appropriation. What I tried my best to do was to treat the subjects in the book with care – that is partly why the refugee does not speak; I did not want to speak for him. In the end, all of my writing is about trying to understand something. In this case, a large part of what I was attempting was to understand the complex history of Africa – a history made dark and even more complex by the shadow of colonialism. Where do I, as a white African in the present day, fit into that narrative? It is hard to say. This story is part of an ongoing attempt to find out where I belong within this space; it has never been about taking something for myself.

The island and the country that Samuel comes from are never named. We know only that both are African. Did you have particular locations in mind or are they imaginary composites? I suppose one of the things I am asking here is whether An Island is specifically about South Africa?

They are composites. I have said this in a number of other interviews but I will say it again as I feel very strongly about it: I hate it when people speak about Africa as though it were one country. Yet, here I seem to be doing the same. This was very intentional. At school we learnt about the Scramble for Africa in the late nineteenth century and we were shown a cartoon in which Africa is represented as a cake, with the leaders of Europe cutting it up and each getting a slice. In a sense, I wanted to return to that cake, and I wanted to investigate what damage had been done by the slicing of it.

You have talked about how difficult it was to write An Island. And yet the book flows seamlessly, as if it has been pared back to its essential form. Was that the difficulty, getting the right mix of economy and fluency?

There was so much that was difficult about it. The difficulty of dealing with incredibly complex issues in a nuanced way without seeming flippant or casual. Then the issue of appropriation which you have already raised, and the problem of writing a narrative with so little dialogue or interaction. And then, of course, anything with ‘flashbacks’ is in danger of being dreadfully cheesy.

You are an African writer but you live at least some of the time in Brazil. Does living away from the place you are writing about give you an enhanced perspective on it?

I never think of myself as being completely away. I go back to South Africa every year (except during the pandemic) and do most of the thinking and planning for my writing while there. The actual writing can happen anywhere, because my mind is already in the place where it needs to be – which I realise sounds incredibly pretentious, but I can’t think of another way of saying it. If my mind is there then I am there and therefore the writing is there.

In any event, I am hoping to move back to South Africa permanently as soon as the pandemic allows.

An Island is published 31 August, 2021.