Welcome to the second instalment in our series of Text relatives reviewing books (mainly so we don’t have to listen to them going on about our books at home).

Today’s post is brought to you by Mr Raymond Ballantyne, father of Lucy Ballantyne, one of Text’s tireless publicists.

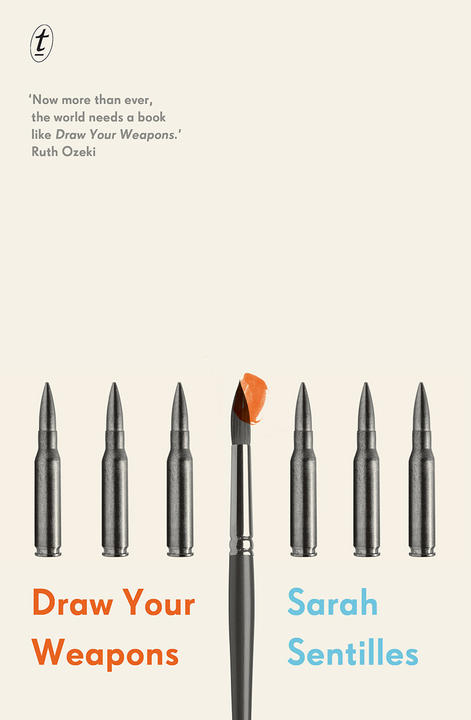

He is reviewing Draw Your Weapons by Sarah Sentilles, a meditation on violence and war and how art can resist and combat both.

Take it away, Mr Ballantyne...

The book arrived by mail. Our daughter, Lucy, had included a handwritten note;

Dad, I’m working on this book about pacifism, art-making etc. Thought you might like it. After three failed attempts where I didn’t get past the preface before being interrupted I finally managed to settle in to a good long read on a flight from Perth to Melbourne.

I am finding it difficult to articulate the feeling that came with reading Draw Your Weapons. Words like familiar, nostalgic and comfortable come to mind, however none of them quite fits my emotional response. This book was certainly something I felt at home with and is important to me.

Sarah Sentilles weaves the story of Howie, a World War II conscientious objector with that of Miles, an Abu Ghraib prison guard from her position as an academic working in art and photography.

Sentilles studied theology before moving into her career in art. I grew up with no religious education, however various teachers at both high school and university introduced me to the writings of former theologians ranging from Morris West to Ivan Illich. Sentilles appears to fit this mould.

Sentilles explores the concept of a moral dilemma, particularly with Miles. She manages to deal with this very difficult subject area in a manner that, like the book as a whole, is very easy to read.

In weaving the stories of Howie and Miles, Sentilles reaches out to other references. I particularly related to her reference to Piccaso’s Guernica, having studied Freud’s analysis of this anti-war work in psychology classes.

She skips the war that shaped my generation, Vietnam. I recall planning strategies with my brothers and our friends to avoid being called up. It is a credit to Sentilles that I, as a member of the generation that is omitted from her book, can still relate strongly to the argument she describes.

If I have one frustration with Draw Your Weapons it is the passages, particularly late in the book, that are unsupported statements of position or philosophy. Perhaps it is just my inability to make what I see as the irrational leap of faith that is fundamental to a religious belief that prevents me from relating to these assertions.

After more than six decades as a pacifist I still struggle with how we are going to achieve peace. The important thing is that we never stop believing that we can. I am delighted that books like Draw Your Weapons are still being written.

Thanks to Sarah Sentilles for writing Draw your Weapons and to Lucy for bringing it to my attention.

And many thanks from Text to Mr Ballantyne for writing his review.

Draw Your Weapons by Sarah Sentilles is out now in all good bookshops, on the Text website (free postage!) and in ebook.

Until next time,

Keep reading,

The Texters