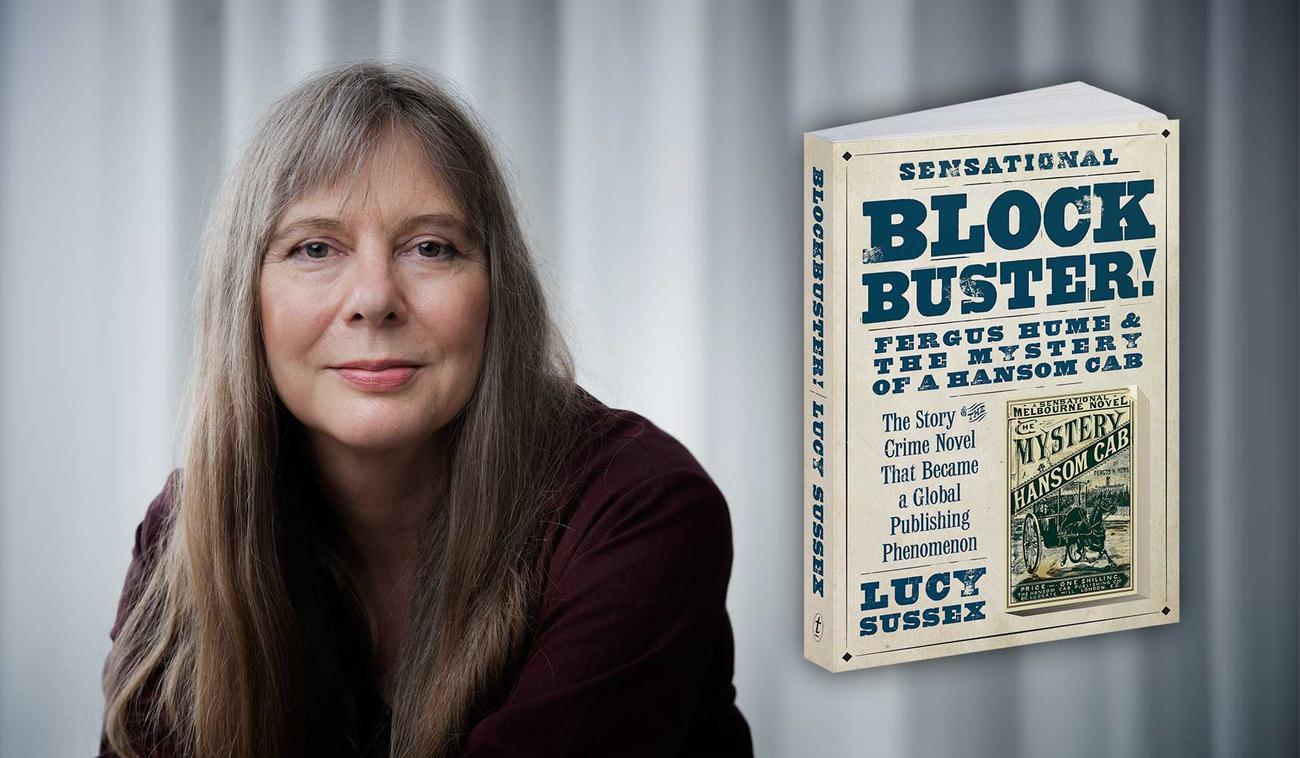

Lucy Sussex is an award-winning author and in her latest book, Blockbuster! Fergus Hume and The Mystery of a Hansom Cab, she delves into the background of one of Text’s most beloved Classics. In doing so, she takes us on a winding tour through the streets of Marvellous Melbourne, probes the history of the crime genre, and unveils the secrets of a book that has never been out of print, Fergus Hume’s The Mystery of a Hansom Cab.

We chatted with Lucy about her book and the publishing phenomenon that inspired it.

When did you first read Fergus Hume’s The Mystery of a Hansom Cab?

When I grew up in Christchurch, New Zealand, I never heard of Hume. In fact I didn’t know about Hansom Cab until I worked as a researcher for crime-fiction historian Professor Stephen Knight, who did several Hume editions. I read it then, and learned about its success. Quite how important a book it was I came to understand in the course of this research.

What were your initial impressions of Hume and the novel?

It came across as a nineteenth-century mystery novel still very readable today (which is not always the case). And a superb picture of 1880s boomtown Melbourne. Of Fergus? A sense of mystery, stronger even than the book.

How many times have you read it since?

Lost count, but each time I pick up something new, like his putting what must be his own address into the text, giving it to hero Brian. Or a really shameless brown-nosing of J. C. Williamson, whom he wanted to stage his plays, as also does an ambitious young man of letters in the novel.

Blockbuster! is the first book to really delve deep into the Fergus Hume story. How did you go about researching his life and that of his books?

The problem with Hume is that he left no descendants, no diaries, there are few letters and the most relevant publishers’ records do not survive. David Green, the Trischler family historian, kindly gave me a lot of information about Fred Trischler, Hume’s brilliant publisher. Rowan Gibbs, Hume’s New Zealand bibliographer, was an endless help. But mostly I used digitised newspapers and other records, which provided more than enough for a book about Hansom Cab alone. Which is a fascinating story in itself.

After so many years of research did you find it difficult to begin the writing process? Were you ever concerned that the research phase would become all-consuming?

I researched as I wrote, aware that more and more digitised material was coming online. I just had to hope that none of it would completely contradict my narrative. As it happened just before the book went to press I got dress details (though no photo) of Jessie Taylor, who owned Hansom Cab’s copyright. It was very hard to stop researching, given what was happening online. Perhaps I never will stop...

In Blockbuster! you discuss how Hume’s Melbourne provided the ideal melting pot for the making of a literary bestseller. How do you think Melbourne’s reading public has changed since this time?

Not necessarily, as the place is still full of keen readers. Even in the 1860s the market for books in Melbourne was ‘huge’. They just have a lot more distractions, like social media etc.

Why do you think Hume’s portrait of Melbourne remains so iconic?

There is nothing quite like it, Ada Cambridge’s novels apart. He sees exactly what is important and interesting in the place, and writes it down, very well. He also sees that the boomtown cannot last, either. Glory and impending doom, a great combination.

To what extent do you think Hume’s New Zealand upbringing and outsider status in Melbourne informed his ideas in the book?

One helluva upbringing, to grow up in the madhouse his father managed. But it gave him an extraordinary knowledge of abnormal psychology. Theatre was used as therapy in the asylum—that made Fergus want to be a playwright. Dunedin was a very cultural place, then and now, and it educated him as a literary man. As an outsider in Melbourne he could observe it dispassionately, and because it was harder to succeed without connections, he put everything he had into the novel. He did so want it to advertise him as a cultured and clever chap, who could write good plays.

What does the Melbourne of today still share with Hume’s Melbourne?

Some of the architecture, though not nearly enough. Death to developers and style-blind architects! The hidden secrets. The desperate chase for money.

What would be some must-see hotspots on a hypothetical ‘Fergus Hume Walking Tour of Melbourne’?

If you walk across the Fitzroy Gardens, you retrace his walk to and from East Melbourne—little has changed. Scots Church, where the novel begins. Perhaps some enterprising soul will send Hansom Cabs up St Kilda road, but now the open carriages suffice. For the opium dens and slums of nineteenth-century Melbourne we would need a time machine.

Why do you think Hume’s subsequent novels were unable to match the success of his debut?

He got it absolutely right on his first attempt, not with his best novel, but with the one which anticipated the market demands. He subsequently devalued his personal brand with some hurried work, and confused it by ventures into children’s writing, utopias and disaster novels. What he was best at was detective writing, but by the time he wrote works such as the superb The Silent House, he was no longer leading the market.

What do today’s crime novels owe to Hume and The Mystery of a Hansom Cab?

It helped create the market category of detective writing, and show publishers how well it could sell. Without Hansom Cab the Sherlock Holmes series might have stopped with A Study in Scarlet—Doyle certainly intended it as a one-off.

Why do you think The Mystery of a Hansom Cab is currently experiencing a renaissance of sorts among readers today?

It’s never been out of print. The telemovie helped, but there is something alluring about ‘our valiant old cab’, to use Miles Franklin’s description.

Come along and celebrate the launch of Lucy Sussex’s Blockbuster! at Reader’s Feast Bookstore on 1 July.