Australian fiction lost a titan when Peter Temple passed away in March of last year. The winner of five Ned Kelly Awards. The winner of the Crime Writers Association of the United Kingdom’s Gold Dagger Award. Author of the only crime novel to win the Miles Franklin Literary Award. The South African who adopted Australia as his home and saw us more clearly than most who were born here. A literary giant.

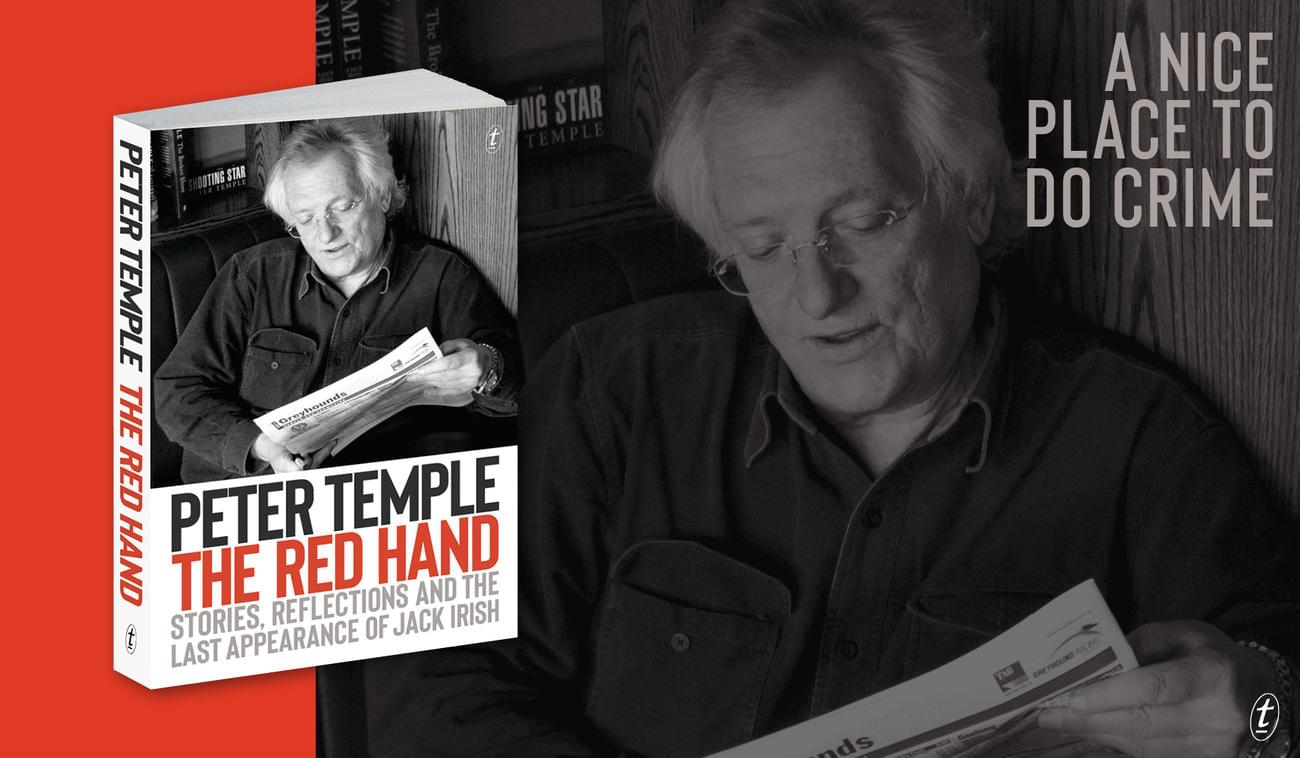

The Red Hand, published earlier this month, is a tribute to Peter Temple and a reminder of what we’ve lost. It contains a sizeable chunk of what would have been the fifth Jack Irish novel, short stories, a film script, his brilliant book reviews, essays and autobiographical musings about Australian life – like this one: ‘A Nice Place to do Crime’.

Enjoy.

Apart from In the Evil Day, set in Europe, the US, and elsewhere,

all my books have Australian settings. I’m proud to be an identifiably Australian writer because I came to the country as an

adult – an extremely grateful adult. I’ve tried to capture my affection for the people and the place in my novels and to tell Australian stories. Becoming an Aussie was helped by the fact that I arrived without a single shred of nostalgia for an ‘old country’. My old country was apartheid South Africa and I had a profound distaste for the behaviour of its white population, never missed it, never wanted to go back. This is not to say that Australia doesn’t have a shadow side, that it has transcended its history of transgressions against the original inhabitants. It hasn’t. But the good people (and I think they are in the overwhelming majority) care about the past and want reconciliation

and a fairer world for all Australians. It’s a work in progress. It’s also an amazing place where you can be at a rodeo, look over your shoulder and see a cricket match in progress, men in white flannels

shouting Howzat, the umpire raising an index finger and saying, ‘Out.’ I always had the urge to write, but I took early retirement after writing a cowboy novel – of the two pearl-handled Colts variety – when I was about ten. By then, reading hungrily and without discrimination, I had polished off the children’s section of the library. I was given special dispensation to take out adult books approved by the librarian. I got around her by getting my innocent other to take out books like Peyton Place. At school, I was forced to learn poems and chunks of Shakespeare by heart. I think it did some good. I love the slicing one-handed backhands of poetry, the quick, daring artistry at the net, the unplayable

aces. In my mid-teens, I discovered American writers who swept me away: Hemingway, Fitzgerald, O’Hara (oh, that high-society sex), Mailer, McCullers, Baldwin, Capote, and, most of all, the silky and unutterably sad John Updike. Another important thing that happened to me was a friend’s mother introducing me to reading plays. If I have any ability to

write dialogue, it comes from reading at least thirty volumes of Best American Short Plays. This worthy annual introduced me to Tennessee Williams, Albee, Odets, Miller, Mamet, Wilder. I still love reading plays and revere no writer more than the British minimalist Harold Pinter. Later on, in my early working life and at university, I devised a literary canon for myself, chewing my way through the complete works of writers good and bad. I now suspect that this put a dampener on my creative urges. I haven’t been much influenced by crime writers. One reason I took to writing the stuff was that I found almost everything new I opened to be formulaic. But I have a few old loves and a few newer ones – Margery Allingham, John D. MacDonald, Ross Macdonald, James Hadley Chase, Elmore Leonard (for his wonderful ear and

indifference to the props on which so many writers rely), James Crumley, Charles McCarry (without peer in the spy novel, so much better than the indulgent and cloying Le Carré). I’ve never had what I felt was a proper job. Sad, really. I’ve been in reasonably gainful employment – newspapers, magazines, teaching journalism, editing, writing – but I never had the feeling of having a career. I was just waiting for my vocation to announce itself. And one day I began writing and it did. It’s not that writing comes easily to me. Being stuck is the rule, not the exception. In fact, for me writing is one long attempt to become unstuck. I move from one impasse to another. Most of the time, I am convinced that the whole enterprise is a mistake and doomed. This kind of anxiety would be acceptable if I believed I was creating art, but I don’t, and that knowledge serves to make matters worse. An

ordinary sentence, like an ordinary piece of joinery, isn’t dignified by the time it took to make. I’ve also found that inspiration isn’t something that lasts beyond a paragraph or two. Creative rushes are also to be distrusted. It’s the passages that flowed from your fingertips that you have to axe the next day. The ideas I have for books are also much too vague and ephemeral to be called inspirations. For me, they take the form of images and the feelings that come with them, scenes seen and imagined, usually unconnected, isolated, not part of any narrative. I’ve usually forgotten them by chapter three. The first Jack Irish book was inspired by seeing two lawyers drinking in a backstreets pub in inner-city Melbourne, worldly men in dark suits talking shop and laughing a lot. Then I created the Irish family history. It fills pages and pages. Most of the detail I’ve never used but it enabled me to see

Jack whole – a man in his place, in his time, in his history. I think it gives a certain depth and complexity to the character. Jack Irish seems to have struck a chord in Australian readers. I’m delighted to say that people come up to me and talk about him in terms usually reserved for close friends. Creating singular characters is difficult. And then there is plotting.

I must confess to hating plotting. I like travelling without a map, falling into holes, straying down dark alleys into cul-de-sacs, waiting for the electrifying moment when the story wants to tell itself to me, when characters turn their faces to me and speak. I sometimes think that writing decent crime novels is a higher calling. People will read the most boring and pointless literary novels because they seem somehow improving. They don’t expect to be entertained. They expect to emerge as better human beings. Crime receives no such indulgence. So, even in portraying the world at its darkest, the crime writer has to be aware of what the punters have come for. And, the genre limitation aside, I think there is as much good prose in crime as in any other fiction – possibly more. But I would say that, wouldn’t I?