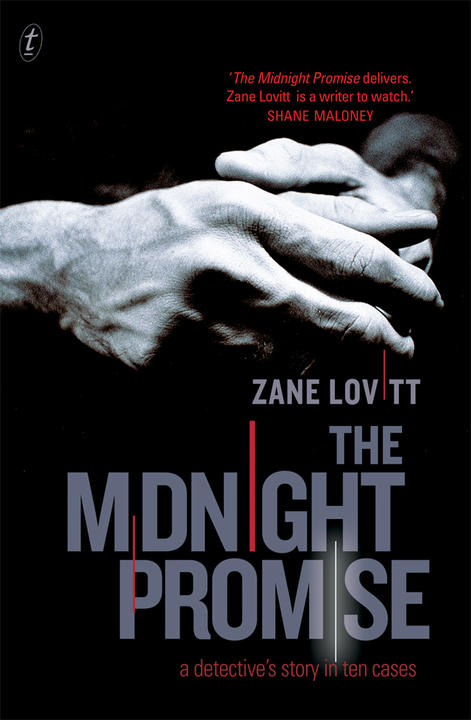

Zane Lovitt’s debut, The Midnight Promise: A Detective’s Story in Ten Cases, is a brilliant hardboiled crime novel set in Melbourne. We asked Zane about his inspirations and his advice to aspiring writers.

The Midnight Promise is your first novel. Can you tell us a little about how you began writing fiction?

I’ve been writing fiction ever since I’ve been writing, in amongst the shopping lists and the text messages and the grumpy notes to housemates. Even when I was studying journalism I got cracking marks for the stories I simply made up. For a while I thought I’d get my fix writing movies rather than prose. There are ten thousand reasons why that didn’t work out (and thank God it didn’t), but the primary one is that, when you write for the screen, you write what the guy with the money tells you to write. Pursuing a novel (and having no editor, no deadline and no plausible hope of ever getting published) meant that I could write whatever I liked. I’m into self-gratification.

At the centre of The Midnight Promise is the terrific John Dorn. He’s a hapless and world-weary private investigator who is hurtling toward his own personal truth. Who is John Dorn? And was there any particular inspiration for this character?

I like the mix of suspense and humour that a private detective story can provide, and I wanted to give that mix some nuance that I think is often missing from hardboiled fiction. I like Raymond Chandler and everything, but reading him in the twenty-first century…Philip Marlowe is really a bit of a douche bag. I wanted to write a character who was entertaining but who was first an effective operator, not merely a smart-arse with a preternatural measure on everybody.

A private investigator was also appealing because the very definition of hardboiled fiction is that the story unfolds with a high level of subjectivity. I’m attracted to the idea of the audience getting right inside the character’s head and experiencing the story as they do, incorporating the least amount of what John Gardner calls ‘psychic distance’. Hardboiled comes ready-made for that.

Your novel has a very impressive structure and unfolds in ten cases, a little like episodes. Can you tell us why you chose this form for the novel?

Honestly, I never chose it. Ten years ago, when I decided to write a crime novel, I was confronted immediately by the fact that I didn’t know how to write a crime novel. I resolved to write some short (very short) stories to develop the character and the voice, during which time I would plot out the novel. Over time, I found the short story writing was getting me out of bed in the morning, while the novel-length story was plodding and hazy. My answer to this was to plan to include some of the stories in the book itself, interrupting the main story with tales from John’s life. But some of the shorts grew to ten or fifteen thousand words, which is beyond anything you could reasonably call an interruption. I was enjoying the short story writing so much that the full-length story fell away and I was left with a solid character arch for John Dorn, one that took place in the background to his work as a private detective.

Do you have any writing tips for aspiring writers?

Ray Bradbury died recently and there have been some clips of his lectures and interviews doing the rounds on the internet. In one of those clips he described himself as a ‘collector of metaphors’. I’m no die-hard Bradbury fan, but I think a collector of metaphors is a pretty neat thing for a writer to aspire to be. Metaphor is the ultimate tool in fiction—it can underpin a single sentence or an entire novel.

Who are your favourite writers?

I’m afraid none of them are crime writers: Chuck Palahniuk, Cormac McCarthy, Kurt Vonnegut, Helen Garner, Amy Hempel, Mark Richard, Dennis Johnson, Mary Robinson, Raymond Carver. Dashiell Hammett is my favourite writer of hardboiled fiction, so let’s chuck him in there as well.

Finally, what are you working on at the moment?

Two novels are competing for my attention right now, one short and one long. The short one is traditional noir, which is a genre that doesn’t seem to get published much in Australia, and I’m trying to figure out if it has any place at all in Australian culture. The other book is an airport novel, an international thriller which I’ve been developing for years and which may require a better writer than I for it to be properly realised. So I beat on, with the ‘crime’ and the ‘suspense’, and I don’t expect to ever write anything else.