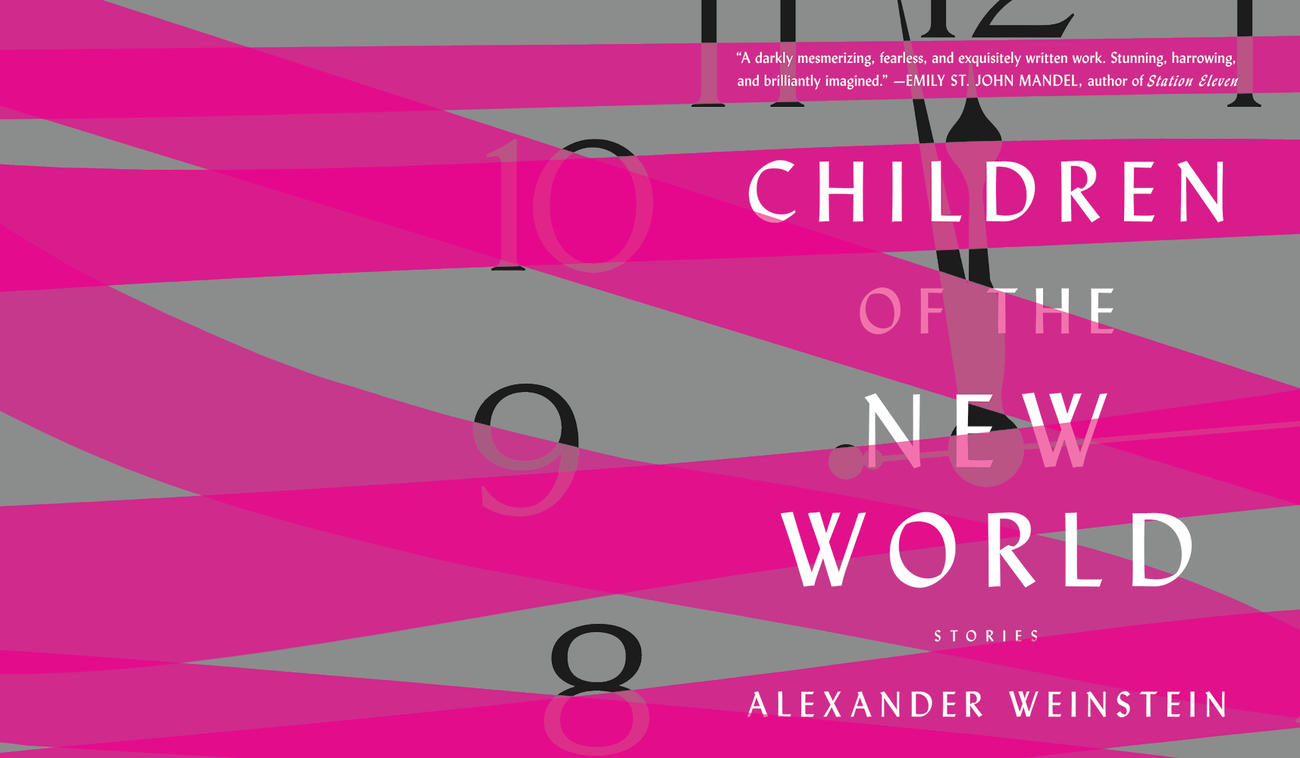

Wonder what the world will look like in a few years? Alexander Weinstein already knows, and Humans, Westworld and Black Mirror have got nothing on him. This dark and haunting debut collection of stories, Children of the New World is being hailed as a brilliant and visionary work. Weinstein has been compared to Atwood, Kafka and Eggers.

‘Saying Goodbye to Yang’ is the first story in this collection. It’s a haunting and prescient tale, exploring racism, our relationship with technology, grief and prejudice. A eerily uncanny prediction of an American future that may all too easily occur.

Saying Goodbye to Yang

WE’RE SITTING AROUND the table eating Cheerios—my wife sipping tea, Mika playing with her spoon, me suggesting apple picking over the weekend—when Yang slams his head into his cereal bowl. It’s a sudden mechanical movement, and it splashes cereal and milk all over the table. Yang rises, looking as though nothing odd just occurred, and then he slams his face into the bowl again. Mika thinks this is hysterical. She starts mimicking Yang, bending over to dunk her own face in the milk, but Kyra’s pulling her away from the table and whisking her out of the kitchen so I can take care of Yang.

At times like these, I’m not the most clearheaded. I stand in my kitchen, my chair knocked over behind me, at a total loss. Shut him down, call the company? Shut him down, call the company? By now the bowl is empty, milk dripping off the table, Cheerios all over the goddamned place, and Yang has a red ring on his forehead from where his face has been striking the bowl. A bit of skin has pulled away from his skull over his left eyelid. I decide I need to shut him down; the company can walk me through the reboot. I get behind Yang and untuck his shirt from his pants as he jerks forward, then I push the release button on his back panel. The thing’s screwed shut and won’t pop open.

“Kyra,” I say loudly, turning toward the doorway to the living room. No answer, just the sound of Mika upstairs, crying to see her brother, and the concussive thuds of Yang hitting his head against the table. “Kyra!”

“What is it?” she yells back. Thud.

“I need a Phillips head!”

“What?” Thud.

“A screwdriver!”

“I can’t get it! Mika’s having a tantrum!” Thud.

“Great, thanks!”

Kyra and I aren’t usually like this. We’re a good couple, communicative and caring, but moments of crisis bring out the worst in us. The skin above Yang’s left eye has completely split, revealing the white membrane beneath. There’s no time for me to run to the basement for my toolbox. I grab a butter knife from the table and attempt to use the tip as a screwdriver. The edge, however, is too wide, completely useless against the small metal cross of the screw, so I jam the knife into the back panel and pull hard. There’s a cracking noise, and a piece of flesh-colored Bioplastic skids across the linoleum as I flip open Yang’s panel. I push the power button and wait for the dim blue light to shut off. With alarming stillness, Yang sits upright in his chair, as though something is amiss, and cocks his head toward the window. Outside, a cardinal takes off from the branch where it was sitting. Then, with an internal sigh, Yang slumps forward, chin dropping to his chest. The illumination beneath his skin extinguishes, giving his features a sickly ashen hue.

I hear Kyra coming down the stairs with Mika. “Is Yang okay?”

“Don’t come in here!”

“Mika wants to see her brother.”

“Stay out of the kitchen! Yang’s not doing well!” The kitchen wall echoes with the muffled footsteps of my wife and daughter returning upstairs.

“Fuck,” I say under my breath. Not doing well? Yang’s a piece of crap and I just destroyed his back panel. God knows how much those cost. I get out my cell and call Brothers & Sisters Inc. for help.

WHEN WE ADOPTED Mika three years ago, it seemed like the progressive thing to do. We considered it our one small strike against cloning. Kyra and I are both white, middle-class, and have lived an easy and privileged life; we figured it was time to give something back to the world. It was Kyra who suggested she be Chinese. The earthquake had left thousands of orphans in its wake, Mika among them. It was hard not to agree. My main concern—one I voiced to Kyra privately, and quite vocally to the adoption agency during our interview—was the cultural differences. The most I knew about China came from the photos and “Learn Chinese” translations on the place mats at Golden Dragon. The adoption agency suggested purchasing Yang.

“He’s a Big Brother, babysitter, and storehouse of cultural knowledge all in one,” the woman explained. She handed us a colorful pamphlet— China! it announced in red dragon-shaped letters—and said we should consider. We considered. Kyra was putting in forty hours a week at Crate & Barrel, and I was still managing double shifts at Whole Foods. It was true, we were going to need someone to take care of Mika, and there was no way we were going to use some clone from the neighborhood. Kyra and I weren’t egocentric enough to consider ourselves worth replicating, nor did we want our neighbors’perfect kids making our daughter feel insecure. In addition, Yang came with a breadth of cultural knowledge that Kyra and I could never match. He was programmed with grades K through college, and had an in-depth understanding of national Chinese holidays like flag-raising ceremonies and Ghost Festivals. He knew about moon cakes and sky lanterns. For two hundred more, we could upgrade to a model that would teach Mika tai chi and acupressure when she got older. I thought about it. “I could learn Mandarin,” I said as we lay in bed that night. “Come on,” Kyra said, “there’s no fucking way that’s happening.” So I squeezed her hand and said, “Okay, it’ll be two kids then.”

HE CAME TO us fully programmed; there wasn’t a baseball game, pizza slice, bicycle ride, or movie that I could introduce him to. Early on I attempted such outings to create a sense of companionship, as though Yang were a foreign exchange student in our home. I took him to see the Tigers play in Comerica Park. He sat and ate peanuts with me, and when he saw me cheer, he followed suit and put his hands in the air, but there was no sense that he was enjoying the experience. Ultimately, these attempts at camaraderie, from visiting haunted houses to tossing a football around the backyard, felt awkward—as though Yang were humoring me—and so, after a couple months, I gave up. He lived with us, ate food, privately dumped his stomach canister, brushed his teeth, read Mika goodnight stories, and went to sleep when we shut off the lights.

All the same, he was an important addition to our lives. You could always count on him to keep conversation going with some fact about China that none of us knew. I remember driving with him, listening to World Drum on NPR, when he said from the backseat, “This song utilizes the xun, an ancient Chinese instrument organized around minor third intervals.” Other times, he’d tell us Fun Facts. Like one afternoon, when we’d all gotten ice cream at Old World Creamery, he turned to Mika and said, “Did you know ice cream was invented in China over four thousand years ago?” His delivery of this info was a bit mechanical—a linguistic trait we attempted to keep Mika from adopting. There was a lack of passion to his statements, as though he wasn’t interested in the facts. But Kyra and I understood this to be the result of his being an early model, and when one considered the moments when he’d turn to Mika and say, “I love you, little sister,” there was no way to deny what an integral part of our family he was.

‘These 13 stories artfully slam an unchecked obsession with technology and affirm the beauty of reality’s texture.’

— New York Times

TWENTY MINUTES OF hold-time later, I’m informed that Brothers & Sisters Inc. isn’t going to replace Yang. My warranty ran out eight months ago, which means I’ve got a broken Yang, and if I want telephone technical support, it’s going to cost me thirty dollars a minute now that I’m post-warranty. I hang up. Yang is still slumped with his chin on his chest. I go over and push the power button on his back, hoping all he needed was to be restarted. Nothing. There’s no blue light, no sound of his body warming up.

Shit, I think. There goes eight thousand dollars.

“Can we come down yet?” Kyra yells.

“Hold on a minute!” I pull Yang’s chair out and place my arms around his waist. It’s the first time I’ve actually embraced Yang, and the coldness of his skin surprises me. While he has lived with us almost as long as Mika, I don’t think anyone besides her has ever hugged or kissed him. There have been times when, as a joke, one of us might nudge Yang with an elbow and say something humorous like, “Lighten up, Yang!” but that’s been the extent of our contact. I hold him close to me now, bracing my feet solidly beneath my body, and lift. He’s heavier than I imagined, his weight that of the eighteen-year-old boy he’s designed to be. I hoist him onto my shoulder and carry him through the living room out to the car.

My neighbor, George, is next door raking leaves. George is a friendly enough guy, but completely unlike us. Both his children are clones, and he drives a hybrid with a bumper sticker that reads IF I WANTED TO GO SOLAR, I’D GET A TAN. He looks up as I pop the trunk. “That Yang?” he asks, leaning against his rake.

“Yeah,” I say and lower Yang into the trunk.

“No shit. What’s wrong with him?”

“Don’t know. One moment we’re sitting having breakfast, the next he’s going haywire. I had to shut him down, and he won’t start up again.”

“Jeez. You okay?”

“Yeah, I’m fine,” I say instinctively, though as I answer, I realize that I’m not. My legs feel wobbly and the sky above us seems thinner, as though there’s less air. Still, I’m glad I answered as I did. A man who paints his face for Super Bowl games isn’t the type of guy to open your heart to.

“You got a technician?” George asks.

“Actually, no. I was going to take him over to Quick Fix and see—”

“Don’t take him there. I’ve got a good technician, took Tiger there when he wouldn’t fetch. The guy’s in Kalamazoo, but it’s worth the drive.” George takes a card from his wallet. “He’ll check Yang out and fix him for a third of what those guys at Q-Fix will charge you. Tell Russ I sent you.”

RUSS GOODMAN’S TECH Repair Shop is located two miles off the highway amid a row of industrial warehouses. The place is wedged between Mike’s Muffler Repair and a storefront called Stacey’s Second Times—a cluttered thrift store displaying old rifles, iPods, and steel bear traps in its front window. Two men in caps and oil-stained plaid shirts are standing in front smoking cigarettes. As I park alongside the rusted mufflers and oil drums of Mike’s, they eye my solar car like they would a flea-ridden dog.

“Hi there, I’m looking for Russ Goodman,” I say as I get out. “I called earlier.”

The taller of the two, a middle-aged man with gray stubble and weathered skin, nods to the other guy to end their conversation. “That’d be me,” he says. I’m ready to shake his hand, but he just takes a drag from his cigarette stub and says, “Let’s see what you got,” so I pop the trunk instead. Yang is lying alongside my jumper cables and windshield-washing fluid with his legs folded beneath him. His head is twisted at an unnatural angle, as though he were trying to turn his chin onto the other side of his shoulder. Russ stands next to me, with his thick forearms and a smell of tobacco, and lets out a sigh. “You brought a Korean.” He says this as a statement of fact. Russ is the type of person I’ve made a point to avoid in my life: a guy that probably has a WE CLONE OUR OWN sticker on the back of his truck.

“He’s Chinese,” I say.

“Same thing,” Russ says. He looks up and gives the other man a shake of his head. “Well,” he says heavily, “bring him inside, I’ll see what’s wrong with him.” He shakes his head again as he walks away and enters his shop.

Russ’s shop consists of a main desk with a telephone and cash register, across from which stands a table with a coffeemaker, Styrofoam cups, and powdered creamer. Two vinyl chairs sit by a table with magazines on it. The door to the workroom is open. “Bring him back here,” Russ says. Carrying Yang over my shoulder, I follow him into the back room.

The work space is full of body parts, switchboards, cables, and tools. Along the wall hang disjointed arms, a couple of knees, legs of different sizes, and the head of a young girl, about seventeen, with long red hair. There’s a worktable cluttered with patches of skin and a Pyrex box full of female hands. All the skin tones are Caucasian. In the middle of the room is an old massage table streaked with grease. Probably something Russ got from Stacey’s Seconds. “Go ’head and lay him down there,” Russ says. I place Yang down on his stomach and position his head in the small circular face rest at the top of the table.

“I don’t know what happened to him,” I say. “He’s always been fine, then this morning he started malfunctioning. He was slamming his head onto the table over and over.” Russ doesn’t say anything. “I’m wondering if it might be a problem with his hard drive,” I say, feeling like an idiot. I’ve got no clue what’s wrong with him; it’s just something George mentioned I should check out. I should have gone to Quick Fix. The young techies with their polished manners always make me feel more at ease. Russ still hasn’t spoken. He takes a mallet from the wall and a Phillips head screwdriver. “Do you think it’s fixable?”

“We’ll see. I don’t work on imports,” he says, meeting my eyes for the first time since I’ve arrived, “but, since you know George, I’ll open him up and take a look. Go ’head and take a seat out there.”

“How long do you think it’ll take?”

“Won’t know till I get him opened up,” Russ says, wiping his hands on his jeans.

“Okay,” I say meekly and leave Yang in Russ’s hands.

In the waiting room I pour myself a cup of coffee and stir in some creamer. I set my cup on the coffee table and look through the magazines. There’s Guns & Ammo, Tech Repair, Brothers & Sisters Digest—I put the magazines back down. The wall behind the desk is cluttered with photos of Russ and his kids, all of whom look exactly like him, and, buried among these, a small sign with an American flag on it and the message THERE AIN’T NO YELLOW IN THE RED, WHITE, AND BLUE.

“Pssh,” I say instinctually, letting out an annoyed breath of air. This was the kind of crap that came out during the invasion of North Korea, back when the nation changed the color of its ribbons from yellow to blue. Ann Arbor’s a progressive city, but even there, when Kyra and I would go out with Yang and Mika in public, there were many who avoided eye contact. Stop the War activists weren’t any different. It was that first Christmas, as Kyra, Yang, Mika, and I were at the airport being individually searched, that I realized Chinese, Japanese, South Korean didn’t matter anymore; they’d all become threats in the eyes of Americans. I decide not to sit here looking at Russ’s racist propaganda, and leave to check out the bear traps at Stacey’s.

'Each of these stories has its genesis in the question "What if …?" and Weinstein's imaginings are far too much like the current state of the world to be anything but chilling. Yet he can also, if only in passing, be very funny.’

— Age

“HE’S DEAD,” RUSS tells me. “I can replace his insides, more or less build him back from scratch, but that’s gonna cost you about as much as a used one.”

I stand looking at Yang, who’s lying on the massage table with a tangle of red and green wires protruding from his back. Even though his skin has lost its vibrant color, it still looks soft, like when he first came to our home. “Isn’t there anything else you can do?”

“His voice box and language system are still running. If you want, I’ll take it out for you. He’ll be able to talk to her, there just won’t be any face attached. Cost you sixty bucks.” Russ is wiping his hands on a rag, avoiding my eyes. I think of the sign hanging in the other room. Sure, I think, I can just imagine the pleasure Russ will take in cutting up Yang.

“No, that’s all right. I’ll just take him home. What do I owe you?”

“Nothing,” Russ says. I look up at him. “You know George,” he says as explanation. “Besides, I can’t fix him for you.”

On the ride home, I call Kyra. She picks up on the second ring.

“Hello?”

“Hey, it’s me.” My voice is ragged.

“Are you okay?”

“Yeah,” I say, then add, “Actually, no.”

“What’s the matter? How’s Yang?”

“I don’t know. The tech I took him to says he’s dead, but I don’t believe him—the guy had a thing against Asians. I’m thinking about taking Yang over to Quick Fix.” There’s silence on the other end of the line. “How’s Mika?” I ask.

“She keeps asking if Yang’s okay. I put a movie on for her. . . . Dead?” she asks. “Are you positive?”

“No, I’m not sure. I don’t know. I’m not ready to give up on him yet. Look,” I say, glancing at the dash clock, “it’s only three. I’m going to suck it up and take him to Quick Fix. I’m sure if I drop enough cash they can do something.”

“What will we do if he’s dead?” Kyra asks. “I’ve got work on Monday.”

“We’ll figure it out,” I say. “Let’s just wait until I get a second opinion.”

Kyra tells me she loves me, and I return my love, and we hang up. It’s as my Bluetooth goes dead that I feel the tears coming. I remember last fall when Kyra was watching Mika. I was in the garage taking down the rake when, from behind me, I heard Yang. He stood awkwardly in the doorway, as though he was uncertain what to do while Mika was being taken care of. “Can I help you?” he asked.

On that chilly late afternoon, with the red and orange leaves falling around us—me in my vest, and Yang in the black suit he came with—Yang and I quietly raked leaves into large piles on the flat earth until the backyard looked like a village of leaf huts. Then Yang held open the bag, I scooped the piles in, and we carried them to the curb.

“You want a beer?” I asked, wiping the sweat from my forehead.

“Okay,” Yang said. I went inside and got two cold ones from the fridge, and we sat together, on the splintering cedar of the back deck, watching the sun fall behind the trees and the first stars blink to life above us.

“Can’t beat a cold beer,” I said, taking a swig.

“Yes,” Yang said. He followed my lead and took a long drink. I could hear the liquid sloshing down into his stomach canister.

“This is what men do for the family,” I said, gesturing with my beer to the leafless yard. Without realizing it, I had slipped into thinking of Yang as my son, imagining that one day he’d be raking leaves for his own wife and children. It occurred to me then that Yang’s time with us was limited. Eventually, he’d be shut down and stored in the basement—an antique that Mika would have no use for when she had children of her own. At that moment I wanted to put my arm around Yang. Instead I said, “I’m glad you came out and worked with me.”

“Me, too,” Yang said and took another sip of his beer, looking exactly like me in the way he brought the bottle to his lips.

THE KID AT Quick Fix makes me feel much more at ease than Russ. He’s wearing a bright red vest with a clean white shirt under it and a name tag that reads HI, I’M RONNIE! The kid’s probably not even twenty-one. He’s friendly, though, and when I tell him about Yang, he says, “Whoa, that’s no good,” which is at least a little sympathetic. He tells me they’re backed up for an hour. So much for quick, I think. I put Yang on the counter and give my name. “We’ll page you once he’s ready,” Ronnie says.

I spend the time wandering the store. They’ve got a demo station of Championship Boxing, so I put on the jacket and glasses and take on a guy named Vance, who’s playing in California. I can’t figure out how to dodge or block though, and when I throw out my hand, my guy on the screen just wipes his nose with his glove. Vance beats the shit out of me, so I put the glasses and vest back on the rack and go look at other equipment. I’m playing with one of the new ThoughtPhones when I hear my name paged over the loudspeaker, so I head back to the Repair counter.

“Fried,” the kid tells me. “Honestly, it’s probably good he bit it. He’s a really outdated model.” Ronnie is rocking back and forth on his heels as though impatient to get on to his next job.

“Isn’t there anything you can do?” I ask. “He’s my daughter’s Big Brother.”

“The language system is fully functional. If you want, I can separate the head for you.”

“Are you kidding? I’m not giving my daughter her brother’s head to play with.”

“Oh,” the kid says. “Well, um, we could remove the voice box for you. And we can recycle the body and give you twenty dollars off any digital camera.”

“How much is all this going to cost?”

“It’s ninety-five for the checkup, thirty-five for disposal, and voice box removal will be another hundred and fifty. You’re probably looking at about three hundred after labor and taxes.”

I think about taking him back to Russ, but there’s no way. When he’d told me Yang was beyond saving, I gave him a look of distrust that anyone could read loud and clear. “Go ahead and remove the voice box,” I say, “but no recycling. I want to keep the body.”

GEORGE IS OUTSIDE throwing a football around with his identical twins when I pull in. He raises his hand to his kids to stop them from throwing the ball and comes over to the low hedge that separates our driveways. “Hey, how’d it go with Russ?” he asks as I get out of the car.

“Not good.” I tell him about Yang, getting a second opinion, how I’ve got his voice box in the backseat, his body in a large Quick Fix bag in the trunk. I tell him all this with as little emotion as possible. “What can you expect from electronics?” I say, attempting to appear nonchalant.

“Man, I’m really sorry for you,” George says, his voice quieter than I’ve ever heard it. “Yang was a good kid. I remember the day he came over to help Dana carry in the groceries. The kids still talk about that fortune-telling thing he showed them with the three coins.”

“Yeah,” I say, looking at the bushes. I can feel the tears starting again. “Anyhow, it’s no big deal. Don’t let me keep you from your game. We’ll figure it out.” Which is a complete lie. I have no clue how we’re going to figure anything out. We needed Yang, and there’s no way we can afford another model.

“Hey, listen,” George says. “If you guys need help, let us know. You know, if you need a day sitter or something. I’ll talk to Dana—I’m sure she’d be up for taking Mika.” George reaches out across the hedge, his large hand coming straight at me. For a moment I flash back to Championship Boxing and think he’s going to hit me. Instead he pats me on the shoulder. “I’m really sorry, Jim,” he says.

'Weinstein writes sensitively and with deceptive simplicity, slicing into the emotional core of his haunted, self-estranged characters. The more they connect via technology, the less connected they feel…Children of the New World is a nuanced and complex vision of where we as a species might be going — and how, for better and for worse, we're already there.

— NPR

THAT NIGHT, I lie with Mika in bed and read her Goodnight Moon. It’s the first time I’ve read to her in months. The last time was when we visited Kyra’s folks and had to shut Yang down for the weekend. Mika’s asleep by the time I reach the last page. I give her a kiss on her head and turn out the lights. Kyra’s in bed reading.

“I guess I’m going to start digging now,” I say.

“Come here,” she says, putting her book down. I cross the room and lie across our bed, my head on her belly.

“Do you miss him, too?” I ask.

“Mm-hm,” she says. She puts her hand on my head and runs her fingers through my hair. “I think saying goodbye tomorrow is a good idea. Are you sure it’s okay to have him buried out there?”

“Yeah. There’s no organic matter in him. The guys at Quick Fix dumped his stomach canister.” I look up at our ceiling, the way our lamp casts a circle of light and then a dark shadow. “I don’t know how we’re going to make it without him.”

“Shhh.” Kyra strokes my hair. “We’ll figure it out. I spoke with Tina Matthews after you called me today. You remember her daughter, Lauren?”

“The clone?”

“Yes. She’s home this semester; college wasn’t working for her. Tina said Lauren could watch Mika if we need her to.”

I turn my head to look at Kyra. “I thought we didn’t want Mika raised by a clone.”

“We’re doing what we have to do. Besides, Lauren is a nice girl.”

“She’s got that glassy-eyed apathetic look. She’s exactly like her mother,” I say. Kyra doesn’t say anything. She knows I’m being irrational, and so do I. I sigh. “I just really hoped we could keep clones out of our lives.”

“For how long? Your brother and Margaret are planning on cloning this summer. You’re going to be an uncle soon enough.”

“Yeah,” I say quietly.

Ever since I was handed Yang’s voice box, time has slowed down. The light of the setting sun had stretched across the wood floors of our home for what seemed an eternity. Sounds have become crisper as well, as though, until now, I’d been living with earplugs. I think about the way Mika’s eyelidsfluttered as she slept, the feel of George’s hand against my arm. I sit up, turn toward Kyra, and kiss her. The softness of her lips makes me remember the first time we kissed. Kyra squeezes my hand. “You better start digging so I can comfort you tonight,” she says. I smile and ease myself off the bed. “Don’t worry,” Kyra says, “it’ll be a good funeral.”

In the hallway, on my way toward the staircase, the cracked door of Yang’s room stops me. Instead of going down, I walk across the carpeting to his door, push it open, and flick on the light switch. There’s his bed, perfectly made with the corners tucked in, a writing desk, a heavy oak dresser, and a closet full of black suits. On the wall is a poster of China that Brothers & Sisters Inc. sent us and a pennant from the Tigers game I took Yang to. There’s little in the minimalism of his décor to remind me of him. There is, however, a baseball glove on the shelf by his bed. This was a present Yang bought for himself with the small allowance we provided him. We were at Toys“R”Us when Yang placed the glove in the shopping cart. We didn’t ask him about it, and he didn’t mention why he was buying it. When he came home, he put it on the shelf near his Tigers pennant, and there it sat untouched.

Along the windowsill, Yang’s collection of dead moths and butterflies look as though they’re ready to take flight. He collected them from beneath our bug zapper during the summer and placed their powdery bodies by the window. I walk over and examine the collection. There’s the great winged luna moth, with its two mock eyes staring at me, the mosaic of a monarch’s wing, and a collection of smaller nondescript brown and silvery gray moths. Kyra once asked him about his insects. Yang’s face illuminated momentarily, the lights beneath his cheeks burning extra brightly, and he’d said, “They’re very beautiful, don’t you think?” Then, as though suddenly embarrassed, he segued to a Fun Fact regarding the brush-footed butterfly of China.

What arrests me, though, are the objects on his writing desk. Small matchboxes are stacked in a pile on the center of the table, the matchsticks spread across the expanse like tiny logs. In a corner is an orange-capped bottle of Elmer’s that I recognize as the one from my toolbox. What was Yang up to? A log cabin? A city of small wooden men and women? Maybe this was Yang’s attempt at art—one that, unlike the calligraphy he was programmed to know, was entirely his own. Tomorrow I’ll bag his suits, donate them to Goodwill, and throw out the Brothers & Sisters poster, but these matchboxes, the butterflies, and the baseball glove, I’ll save. They’re the only traces of the boy Yang might have been.

THE FUNERAL GOES well. It’s a beautiful October day, the sky thin and blue, and the sun lights up the trees, bringing out the ocher and amber of the season. I imagine what the three of us must look like to the neighbors. A bunch of kooks burying their electronic equipment like pagans. I don’t care. When I think about Yang being ripped apart in a recycling plant, or stuffing him into our plastic garbage can and setting him out with the trash, I know this is the right decision. Standing together as a family, in the corner of our backyard, I say a couple of parting words. I thank Yang for all the joy he brought to our lives. Then Mika and Kyra say goodbye. Mika begins to cry, and Kyra and I bend down and put our arms around her, and we stay there, holding one another in the early morning sunlight.

When it’s all over, we go back inside to have breakfast. We’re eating our cereal when the doorbell rings. I get up and answer it. On our doorstep is a glass vase filled with orchids and white lilies. A small card is attached. I kneel down and open it. Didn’t want to disturb you guys. Just wanted to give you these. We’re all very sorry for your loss—George, Dana, and the twins. Amazing, I think. This from a guy who paints his face for Super Bowl games.

“Hey, look what we got,” I say, carrying the flowers into the kitchen. “They’re from George.”

“They’re beautiful,” Kyra says. “Come, Mika, let’s go put those in the living room by your brother’s picture.” Kyra helps Mika out of her chair, and we walk into the other room together.

It was Kyra’s idea to put the voice box behind the photograph. The photo is a picture from our trip to China last summer. In it, Mika and Yang are playing at the gate of a park. Mika stands at the port, holding the two large iron gates together. From the other side, Yang looks through the hole of the gates at the camera. His head is slightly cocked, as though wondering who we all are. He has a placid non-smile/non-frown, the expression we came to identify as Yang at his happiest.

“You can talk to him,” I say to Mika as I place the flowers next to the photograph.

“Goodbye, Yang,” Mika says.

“Goodbye?” the voice box asks. “But, little sister, where are we going?”

Mika smiles at the sound of her Big Brother’s voice, and looks up at me for instruction. It’s an awkward moment. I’m not about to tell Yang that the rest of him is buried in the backyard.

“Nowhere,” I answer. “We’re all here together.”

There’s a pause as though Yang’s thinking about something. Then, quietly, he asks, “Did you know over two million workers died during the building of the Great Wall of China?” Kyra and I exchange a look regarding the odd coincidence of this Fun Fact, but neither of us says anything. Then Yang’s voice starts up again. “The Great Wall is over ten thousand li long. A li is a standardized Chinese unit of measurement that is equivalent to one thousand six hundred and forty feet.”

“Wow, that’s amazing,” Kyra says, and I stand next to her, looking at the flowers George sent, acknowledging how little I truly know about this world.