‘I followed in the footsteps of Arthur Groom, a young man who explored the “amazing series of parallel ranges that wall the heart of Australia” thirty years before I did.’

Robyn Davidson is the award-winning author of Tracks, the bestselling story about her trek across the deserts of west Australia. This piece is the introduction to the Text Classics edition of Arthur Groom’s I Saw a Strange Land.

Before horses and the wheel our species walked: heads up to survey the horizon, down to follow tracks and gather food. The human body’s proprioception, its internal rhythm, is still geared to walking pace. We soothe our babies with it; our deepest understanding of time is measured by it. When we walk, the unconscious (the machinery that takes up most of the brain’s effort) is free to do its work beneath the surface. Forget Rodin’s sculpture—our best thinking is done on our feet.

There seems always to have been this intuitive connection between walking and cogitating. For the religious, pilgrimage healed the soul. The Greeks philosophised while strolling about. Aborigines went on walkabout as part of ceremonial life.

Where you walk matters as well. City walking is fine if you want to be overwhelmed by stimulus. But country walking, specifically spectacular-landscape walking, allows you to have, as Virginia Woolf put it, space to spread the mind out in.

There is a tremendous freedom in setting off on foot, with minimal fuss and baggage. The constraints of your life fall away, revealing a less cluttered self ‘as pure as a polished shell’, said the Buddha.

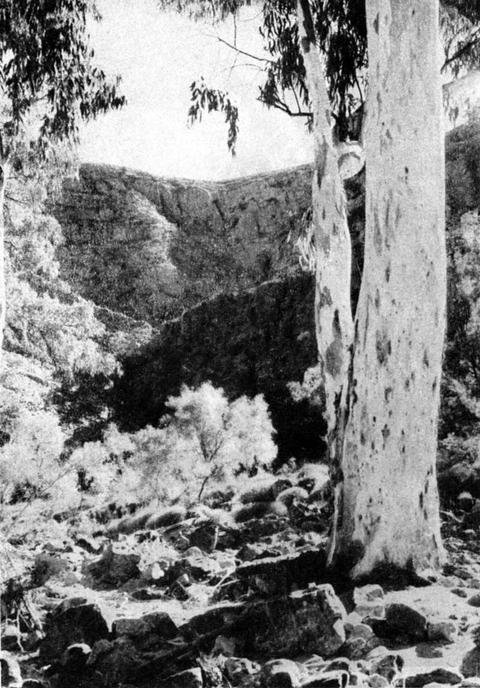

River gum in the Ormiston River bed.

I know this because I did it myself, back in 1977. And, although unaware of it at the time, I followed in the footsteps of Arthur Groom, a young man who explored the ‘amazing series of parallel ranges that wall the heart of Australia’ thirty years before I did. I Saw a Strange Land, first published in 1950, is Groom’s journal account of this trip. And if it were nothing more than lyric descriptions of the terrain he traversed, it would still be fascinating. Sometimes he uses camels to cart his gear, as I did, but mostly he carries what he needs on his back. He thinks nothing of trudging forty miles a day, or night. (You do not know what forty miles is until you have walked it: through sandhills, up and down plunging broken escarpments, along desiccated riverbeds.)

His evocations of the stupendous landscape uncovered memories that I had thought permanently buried. Muscle memories of scrambling over rocks and spinifex, of freezing dawns and hot days, of the unique intensity of being alone in a terrain that is surely among the most affecting in the world. Because I walked the landscape, slept on it, breathed it, drank it, I feel that, in some peculiar way, that country knows me. I am always homesick for it.

Groom even describes an experience I wrote about in my own journey-book, Tracks. A mournful, unaccountable sound, as of something haunting the air, sometimes far off, sometimes close. Both of us discovered (with relief) that it was the pre-dawn breeze, beginning in the high-up gorges, or in the tops of trees, while everything below remained perfectly still.

The range country of the Centre lends itself to those kinds of feelings. We are awed by its age, power and beauty; astonished at the play of light and colour; inhabited by atavistic reverence. If Jehovah is anywhere, then surely he visits the chasms, escarpments and rivers of those primordial hills.

But ways of seeing are mediated by culture. Aboriginal people who belong there have, I imagine, a different aesthetic response. To them, all land is sacred, therefore it is all beautiful. Yet it was Albert Namatjira who first translated the Centralian colours to a European eye. Arthur Groom’s meeting with the Great Man himself, and his talks with Namatjira’s teacher, Rex Battarbee, form one of the many beguiling interludes in the book:

Battarbee had been right. Here was natural colour beyond description. It was high up in the sky, with shades of blue and mauve reflected from the cliffs. It was in the patches of green spinifex, clinging in pinheads on the rubble slopes. It was in the water, the sand, even in the trees; and perhaps the slow-moving deep shadows were more colourful and mysterious than anything else. The colour was in the water-worn rocks of the river bed. There were boulders and slabs of green, grey, mauve, pink, white, red, black, and all the shades between. This colour system was entirely different to the bright colours of the canyon walls. It was of shades and tints, and went up about ten feet to normal flood level, proving that the basic colour of red was gradually being washed out of all the rocks crashing from above.

Groom worries about the effect tourism will eventually have on the area. Will graffiti be carved into the sandstone, or Aboriginal rock art be defaced? But, while it is likely that Jehovah makes himself scarce when buses full of tourists arrive at the better-known gorges and chasms of the MacDonnell Ranges, tourism, it turns out, has been the least of the desert’s problems.

When I set off on my journey, many people thought I was mad; after it was over, I was constantly asked why. Even in 1946, Arthur Groom was thought a little odd, a man who walked when he did not have to.

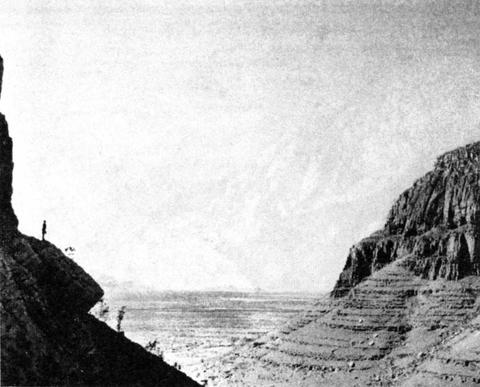

Mangaraka Gorge, of red sandstone, looking back towards distant Haast’s Bluff.

The spark for his journey occurred, he tells us, twenty years before, when he was working as a jackaroo on a cattle station near the Queensland–Northern Territory border. He would have been about seventeen. Out of the eastern horizon a mirage appears: a tiny family and their sheep, heading into the ‘elusive west’, a visual archetype of striving pioneers. He neglects to ask the names of that ‘insane family’, but vows to one day find out their fate, and to do something ‘as brave and big’.

His curiosity is also aroused by ‘one hundred and fifty natives...dirty and diseased, hungry and miserable, the obvious remnants of a dying race’ arriving from the opposite direction, out of the mythological west. He wonders ‘what was being done to ease the passing of Australia’s primitive man’. And so, a year after the end of World War II, he heads for Central Australia.

I find it impossible not to like Groom. You get the sense that he is a decent, somewhat naive young man, at the liberal end of the era’s thinking. He is an early template for the conservationist, and something of a jack-of-all-trades. He is also a natural writer. His descriptions of landscape are in the Romantic mode, and his ear for dialogue is acute and charming. (The book is full of Aussie yarns—dry, comical anecdotes from the characters he comes across.) The scraps of history he weaves into his travels, and the light he casts on the assumptions and attitudes of the time, elevate his book above mere travelogue.

The first story he recounts is the epic of the Lutheran missionaries who journeyed into the desert to build a safe haven for Aborigines, and to teach them something of the Christian God. It is a tale of staggering hardship and grit. Against all odds, they founded Hermannsburg Mission, which is Groom’s first port of call out of Alice Springs. Here he discovers that the ‘Aboriginal race’ is not dying out after all.

In the 1920s Aborigines were still in the process of ‘coming in’ to missions and settlements from distant desert areas. Imagine it: the estates you have successfully managed for at least forty thousand years have been cut to pieces by hard-hoofed animals, invaded by new species of plant and predator, and colonised by people with technology derived from the transition to agriculture. The waterholes and soaks your survival depends on have been fouled by cattle, or used up by the camel trains delivering goods to ‘the Outback’. Foxes, cats and rabbits are already doing tremendous damage to the productivity of your grounds. Bush tucker and indigenous animals are becoming scarce. Then comes a drought. The hunting-gathering economy unravels. And there are whitefella diseases, reprisals for killing stock or settlers, the odd massacre and, above all, hunger. In this unfolding catastrophe, missions and work-for-rations cattle stations provide basic security.

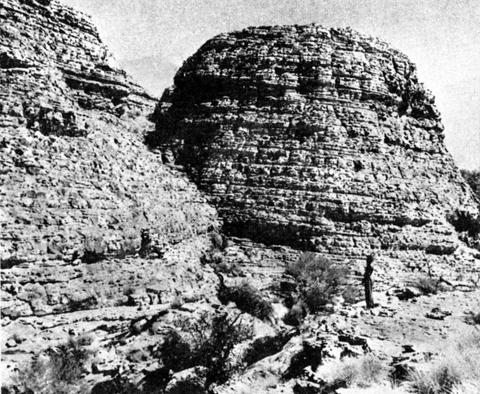

George Gill Range, Central Australia.

Groom does not quite seem to grasp how extraordinary it was that, while many of the ‘pioneers’ could not survive in the desert, Aborigines had managed to thrive. They were able to navigate vast areas of the desert using their understanding of nature, a knowledge welded into an entire poetic conception of reality. They were less technologically advanced, yet infinitely more developed at living in and using the natural world.

While he gives us a sense of the heroism of the missionaries, he cannot quite see that the Aborigines under their care are heroic on a grander scale. His interest in and sympathy for their plight is undoubtedly genuine but his tone can be excruciatingly paternalistic to a modern ear. Sometimes it’s as if his perceptions struggle against the truisms he has absorbed. The truisms tend to win, but then, who can think and live too far outside the received thinking of their time?

We have the benefit of an intervening half century of scholarly research, and can hear the voices of Indigenous people themselves. Carl Strehlow recorded what he knew of their knowledge systems in 1915, but it wasn’t until the 1950s and ’60s that a plethora of publications on Aboriginal history and philosophy became widely available.

These days we can read our way into an appreciation of the intellectual feat of the Dreaming. It is not easy to understand. Sometimes I think that, if non-Indigenous Australians could truly comprehend the reach, complexity and sophistication of Aboriginal cosmology, we would fall on our knees in reverence to human ingenuity and imagination—the instinct towards meaning that unites us all.

I Saw a Strange Land reminds us how little life in the desert has changed. While cities on the seaboard hurtle into the future, constantly transforming themselves, Australia’s remote areas seem hardly to alter at all. The screeching hordes of Aboriginal kids coming out to greet you, their high spirits at odds with the desolation of the camps; the failed, broken-down homesteads; the bogged cars and creaky old windmills—they are all still there. Any changes are subtle, and only observable to an experienced eye. Groom’s account reveals how advanced the process of environmental deterioration was, even back then.

These days we rely almost totally on technology to find our way. When it fails us we become lost, literally and figuratively.

It’s one thing to get lost in a town where help is nearby; it’s quite another to do so when there is no way to reorient yourself. This happened to me once during my walk across the continent, and I will not easily forget the sudden enormity and indifference of the desert around me. The Australian desert is not a landscape to be taken lightly.

Nevertheless, my advice is to take I Saw a Strange Land for a very long walk. Use it as inspiration and guide. Go to the Larapinta Trail, let’s say, a physically demanding but relatively safe introduction to the MacDonnell Ranges. Get out of the car. Ditch the GPS. Use your legs. Rediscover the primal link between walking and thinking. (But don’t forget to take water.)