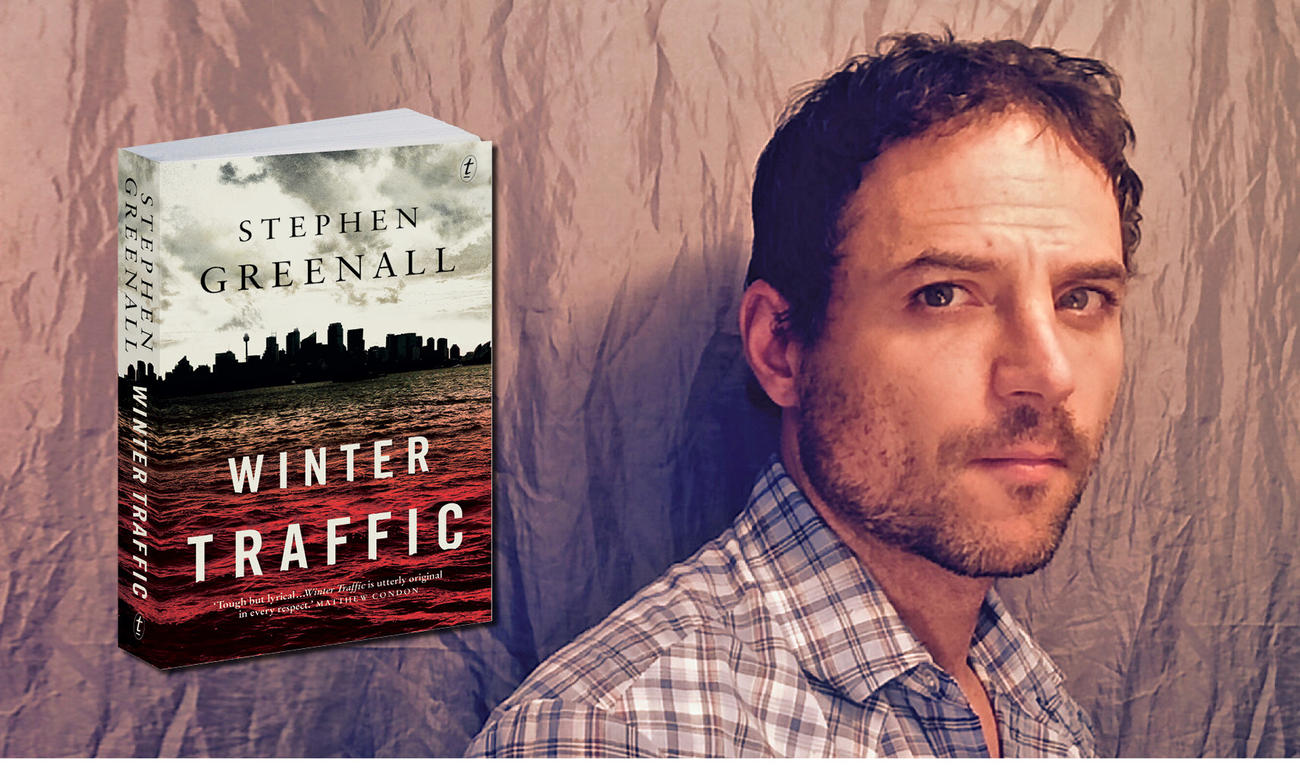

You’ve read the gritty extract, now find out about the person behind it. Stephen Greenall, the author of Winter Traffic, talks to us about Kings Cross, sloth and treating readers as equals.

Winter Traffic is set in Sydney in the nineties. What is it about Sydney in the nineties that drew you to writing about that period?

Without being an historian of that (or any) period, it’s a moment—1993ish—that does feel like a fault line between distinct flavours of Sydney time. Historically, much of the city’s glamour has derived from its propensity for open sin, but I think a certain way of illicit living that was viable between the fifties and the eighties hit a kind of brick wall around then, the wall of a more official (officious) transparency. In terms of cops and robbers more specifically, the mid-nineties period don’t seem to propose the same kind of awesome mythic characters that prior eras did. This could be bullshit—a function of my particular age more than anything else—but it’s the gut feeling I had and followed: late Greiner/early Keating, when the final dinosaurs expired in a glare of harsh new light.

Your novel has a unique voice, but it’s also an absorbing crime book. How did you balance the needs of the genre with your strong writing style?

Badly—at least for a long time. The protagonists were vivid from the start, and I did have a clear idea of their final destinations—but plot is not a strength / the less I have to do with it the better. Character is destiny is super hoary, super true, but it’s also incomplete: Character [+time] = destiny. That’s both book-time and time out here, in the world, where I spent many barren stretches just waiting around for updates.

You once lived in Kings Cross, Sydney, where parts of Winter Traffic take place. What was that like, and do you think it shaped your writing in any way?

I was just back from two years in London, and the narrow stretch of Cross that leads down into Elizabeth Bay struck me as the only place in Sydney you could readily confuse for Europe: something about the cosmopolitan squalor of it. There’s no sandstone, but it’s palpably the most ‘storied’ place in the city: a lot of love/hate/sex/drugs/violence/humanity has etched itself into every scuffed and lovely surface. It’s the Sydney-ist place in Sydney and for a heroically long time it successfully endured the weight of that self-awareness—a grotesque self-parody but no more resistible for that. My year there (2010) was definitely a time when the theme-park aspect of the district was reaching unsustainable levels of zoological ferocity on Friday/Saturday nights. At present the circus is in lockdown—but the Cross is the ultimate survivor.

You’ve also lived abroad quite a bit, and you spent most of that time alone. What are the benefits and challenges of solitude when you are writing?

The mind is a pretty hungry animal. And omnivorous/will eat whatever’s lying around. I am lazy and have a short attention span, so it’s good to wander in places where I have no frame of reference. That’s true for almost everyone—we are each inspired by new things, new settings—but the flipside is the loneliness that attends if the solitude is a long one. That’s when sloth is not an option for the brain; it has to keep busy to keep sane/whole/tenable. It has to (and does) actually work to remain interesting to itself. And places where English isn’t spoken, or is but in very different ways, are excellent for the purpose: you can almost feel the brain starving for language, so it quickly learns to produce its own.

What do you think makes a good crime novel?

We’re encouraged to think of ‘crime’ as a neat generic sticker that makes life convenient for the browser and the bookseller. But when you read the Gold Dagger types, you realise that crime is actually Everything: deftly wielded, crime novels have a capacity to impinge upon pressing social questions and timeless existential predicaments. So I always admire stuff that plays around with formula (or disregards it) to explore the fuller possibilities of what crime more essentially is. Jim Thompson comes to mind, and the later phases of Cormac McCarthy, Peter Temple, Patricia Highsmith. Crime in the blood-soaked hands of such practitioners is a plastic that goes beyond the answering of (even fiendishly tangled) forensic questions. A frontline Elmore Leonard is everything a reader could ask of literature: a rich vocalism that betokens splendid, hard-won technique; a crisp and consistent delineation of a certain type of human condition; an unfailing sense of place. The best (literary crime) novels have a quiet self-respect that never blunders into pretension. They always treat the reader as an equal.

Pretty good stuff, eh? Now go read the extract again and then go get the book.