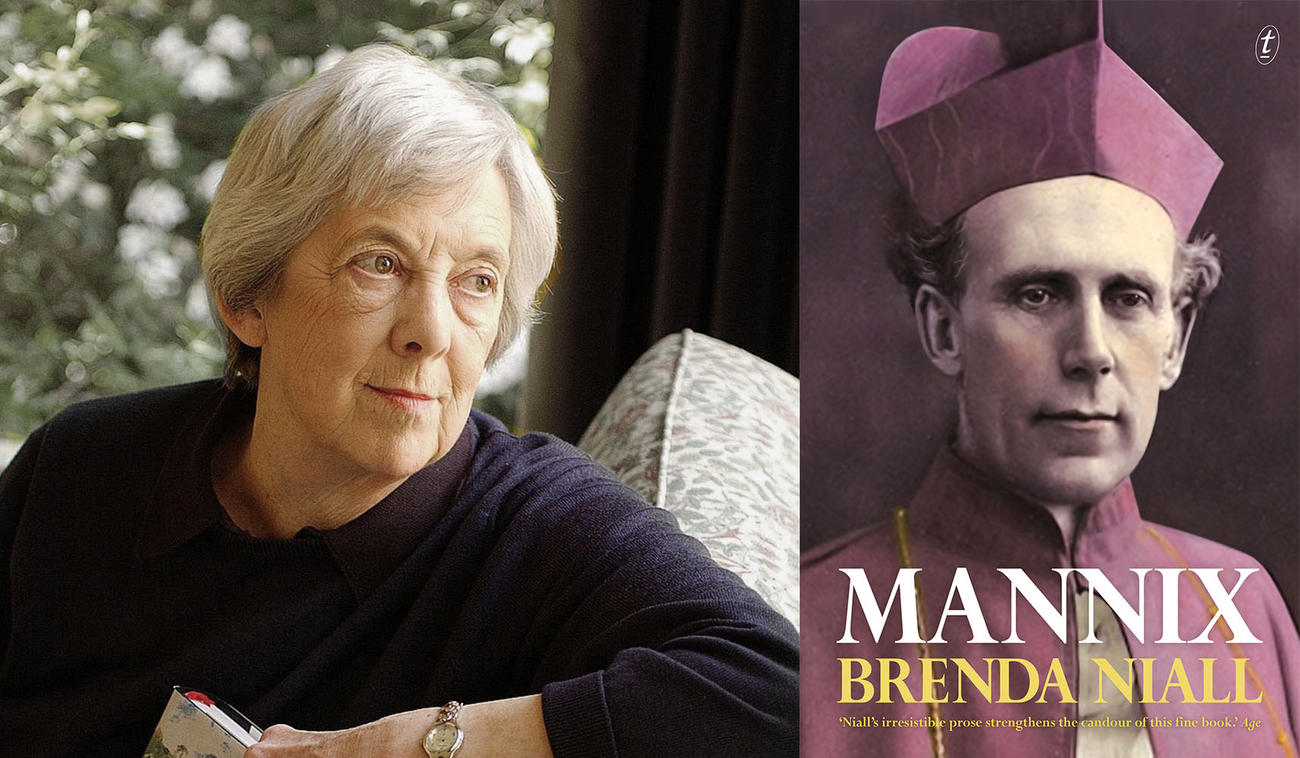

Congratulations to Brenda Niall on being awarded the 2016 Australian Literary Society’s Gold Medal for Literature for her biography Mannix. This magnificent work is the first biography to win the medal in the eighty-eight-year history of the ALS award.

Read on for a glimpse behind the scenes of the work of one of our most highly esteemed biographers and her particular challenges and rewards in researching one of Australia’s most prominent historical figures.

The Lucky Biographer

Brenda Niall

‘Another life of Mannix. Really? Haven’t there been quite a few already? And is it true that there are hardly any papers?’

I had some doubts about writing a life of Archbishop Daniel Mannix. I had written biographies of the Boyd family of artists, on portraitist Judy Cassab, the creative Durack sisters, Mary and Elizabeth. But an archbishop?

Clerical lives are too often reverential. They celebrate; they don’t admit imperfection. It’s a closed world, and a woman biographer trying to enter it might be called courageous in the Yes Minister sense. Looking through the hefty official biography of Mannix, I found this terrifying sentence: ‘The archbishop, as always, was right.’

Daniel Mannix was reserved, shy, even reclusive, but he could enthral an audience of many thousands. He evoked love and fury inside the Catholic church, enmity and a reluctant admiration outside it.

From his anti-conscription crusade during the first world war to his anti-communist stance in the 1950s, he made politicians on both sides nervous. Elegantly chiselled sentences, deft timing, and a mischievous wit made him a formidable figure in public debate.

Clerical lives are too often reverential. They celebrate; they don’t admit imperfection. It’s a closed world, and a woman biographer trying to enter it might be called courageous in the Yes Minister sense.

An engaging subject, but what could I add to the existing record? Biographers thrive on discoveries and private papers. I was the ninth Mannix biographer. Unless there was new material and a new understanding, why bother? Although I never hoped for the astonishing discovery of unknown letters that came late in the project, I was optimistic enough to believe that questions from a different viewpoint would bring fresh insights into the enigmatic Mannix.

I also had assets that future biographers won’t have. I’m old enough to remember Mannix well. I first met him in 1937, when I was six years old. My family’s house was in Studley Park Road, Kew, a few minutes’ walk from his majestic, uncomfortable mansion, ‘Raheen’. Grand furniture, I remember, but no soft surfaces, and only a three-bar radiator against the chill of his enormous library. Like other local children, I took for granted the spectacle of the archbishop’s famous daily walk to work at St Patrick’s Cathedral. He kept it up till he was ninety. His cloak, top hat and buckled shoes belonged to another century; a piece of pure theatre, they never varied.

I was in my twenties, an arts graduate, not yet focussed on a career, when I was employed by B. A. Santamaria to interview Mannix for a new biography. The first interview was a little comedy in which the ninety-five-year-old prelate easily wrong-footed the naive young woman. He was happy to tell me things that I already knew, but he wouldn’t talk about his family or his childhood in Ireland.

Eventually, I gave up on this frustrating project. But, first, I made one more attempt to get personal material. A big box was sent from the cathedral by Bishop Fox. When I opened it, breathless with anticipation, I found only Christmas cards and little pictures of the saints sent to Mannix by grateful parishioners over the years.

Whatever happened to that box, I wonder? Its contents probably went to the incinerator, with other papers, after Mannix’s death. Tom Hazell, a former Melbourne University administrator and veteran cathedral insider, was an altar server for Mannix from the age of six. ‘Bishop Fox was ordered by Mannix to burn his papers,’ Hazell told me. ‘Fox always obeyed Mannix literally—and he wasn’t much interested in history anyway.’

I heard the same account from a subsequent archbishop of Melbourne, Frank Little, (it was vandalism, Little said) and from the Brisbane scholar, Father Tom Boland, who badly wanted Mannix papers for his biography of Archbishop Duhig. Both remembered that the burning was done by May Saunders, Bishop Fox’s housekeeper. ‘It took her three days,’ Boland wrote.

Paul Duffy, a young Jesuit and later a provincial of the order, was at Campion Hall, opposite Raheen, when Mannix died. He helped B. A. Santamaria to pack and hastily remove two suitcases of papers. There were more in cupboards, Duffy said. ‘Bob took the ones he needed, for his biography of Mannix.’ The survival of these papers was unknown for more than three decades. After Santamaria’s death in 1998, his family brought them to the cathedral archives. Just how much was burned in 1963 we will never know. But unless the housekeeper exaggerated grossly, she had a three-day task.

Tom Hazell spoke of ‘the sack of Raheen’. No one knew what to do with personal things that the new archbishop, Justin Simonds, then flying home from Rome, wouldn’t want. There was no guidance in Mannix’s brief will. Books, walking sticks, the military cap of chaplain-general of the armed forces—something Mannix never wore but wouldn’t relinquish—were given away.

Hearing about so much that had been lost or destroyed, I had to think laterally. Yes, many letters to Mannix had gone up in smoke—no shredders then—but what about the outgoing ones? He couldn’t control all of those, and a search in Irish and Australian archives brought some treasures in the characteristic Mannix handwriting.

The public record was vast. Remarkably, Mannix said Sorry to the indigenous people in 1938, and he spoke against the wrongs done to the Jewish people as early as 1933. His reproaches on racial prejudice resonate today.

Mannix said Sorry to the indigenous people in 1938, and he spoke against the wrongs done to the Jewish people as early as 1933. His reproaches on racial prejudice resonate today.

My biggest surprise was the unknown draft letters Mannix sent to six radical cardinals at the Second Vatican Council early in 1963. These were the treasures I had never imagined. ‘Mindblowing!’ said Eureka Street consulting editor Andy Hamilton when I asked what he thought of them.

You would expect a ninety-eight-year-old archbishop to take a cautious line on church reform but these letters show Mannix stirring the pot. He wanted a more humble church; he voted against legalism, clericalism and a ‘hardness, even pride’ that he discerned in council documents. The individually crafted letters speak with Mannix’s unmistakable voice. Who tucked them away in the cathedral safe for this lucky biographer to read, half a century on?

Mannix had an extraordinary presence. I had wondered if that would be remembered, fifty years on. I needn’t have worried. We had two launches. One was in the domed dining hall at Newman College, which is itself a monument to Mannix’s stubborn championship of Walter Burley Griffin’s innovative design. The second was at Raheen where its owner, Jeanne Pratt, welcomed one hundred guests to a sumptuous afternoon tea in the elegantly refurbished drawing room.

I invited people who remembered Mannix, or remembered him through their parents. They had inherited family stories in which, for better or worse, the inimitable Dan had starred. Some had been to Raheen as children, as I had.

Signing books downstairs, I watched my contemporaries hesitate at the invitation to go up and see Mannix’s bedroom and chapel, still as plainly furnished as they were in his time. Was it really allowed? The decades fell away, and they looked momentarily daring as they set foot on the staircase to that very private space.