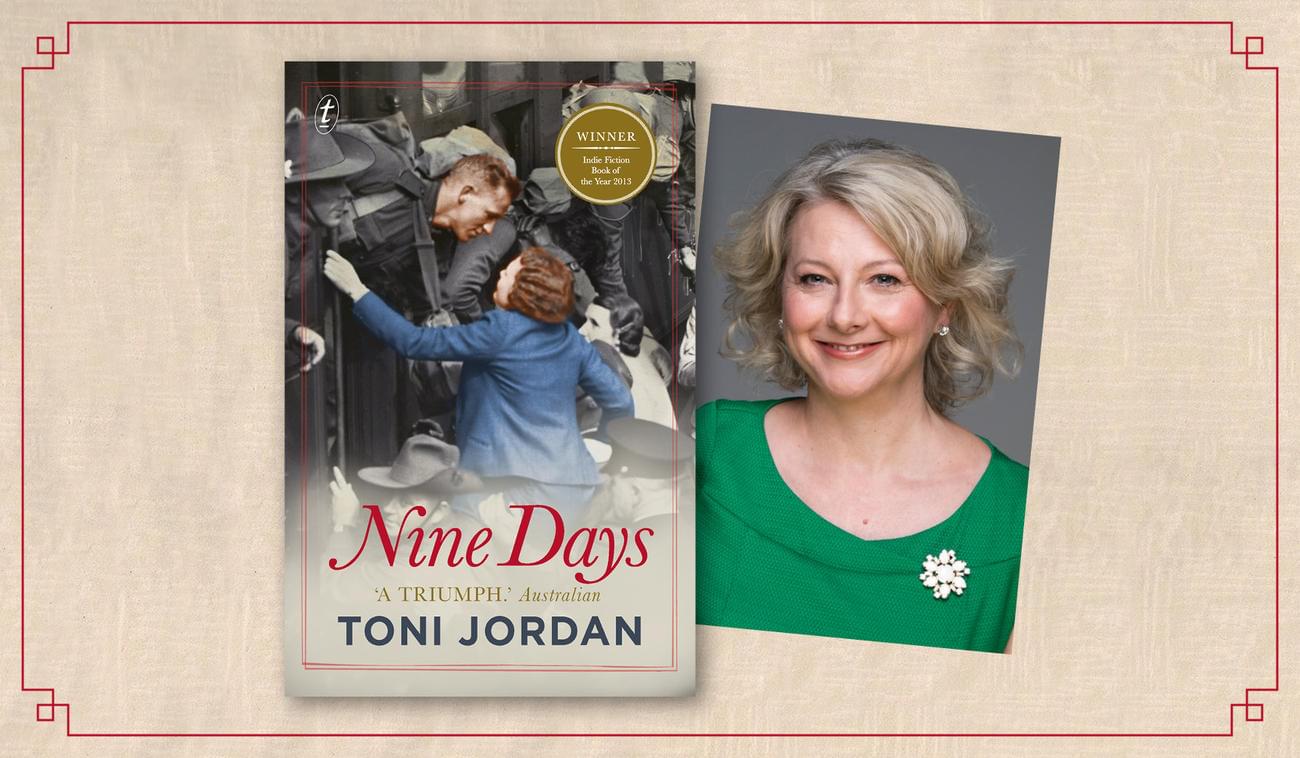

We are incredibly excited to announce that Toni Jordan’s Nine Days has been selected for the VCE English and English as an Additional Language (EAL) text list for 2019! Toni spent some time discussing the themes of the novel with Jill Fitzsimons, Director of Professional Learning & Partnerships and English teacher at Marcellin College, and we’re delighted to present that interview here...

Jill Fitzsimons: Congratulations on making it onto the VCE English/EAL text list, Toni. You and your characters will become extremely important people in the lives of a vast array of VCE English teachers and students! One of the first things students and teachers will begin studying is the world of text and the explicit and implied values it expresses. Can you kick start this process for everyone by teasing out the different worlds in Nine Days? Which overt and hidden values do you associate with these worlds?

Toni Jordan: Thank you Jill! I’m thrilled. I think of Nine Days having two levels of worlds. The first level is the big picture things that the characters have in common with each other (and with other people as well): the location of Richmond, and the specifics of each particular day. The values here are more general and universal, like fear for Australia and for the Allies during WWII, or the economic and political realities of their point in time. Then, if you zoom in, you see that each character has their own individual, specific world that is theirs alone. Each one of them makes their own world through their own thoughts, values and priorities. To me, these two worlds illustrate the difference between a communal and an individualistic world view, but it’s not either/or. They’re overlapping.

JF: Religious sectarianism is a strong external force in the novel but this will be a strange and unfamiliar concept to the majority of students. How deeply entrenched was religious prejudice in twentieth-century Australia and which characters did you use to highlight the conflicting perspectives of Catholic and Anglican families?

TJ: This kind of religious prejudice was a real force in the lives of many people, and one of those big-picture world views that pervade the whole story. Catholics and Protestants shopped in different stores, worked in difference places and socialised very differently. Many families and relationships were torn apart. In Nine Days, this is seen most keenly in Connie and Jack, but there are hints in the lives of the other characters as well.

JF: Nine Days also explores the limitations of the Westaways’ world, particularly in relation to class and gender. Even though Kip and Connie are also extremely bright and full of potential, Francis is the only one who is able to continue his education after Tom’s death. How much control do you think Kip and Connie really had over their destinies, given the context of their lives?

TJ: Of course there are always individuals in history who become trail-blazers; women and working-class men who are the exceptions that prove the rule. People like that are fascinating, but I didn’t want to create anyone like that for Nine Days. I wanted a family of average people. I think it was very common in the mid-twentieth century for grief to derail someone’s career prospects, if they were a sensitive kind of person like Kip. It was normal for women, however bright, to leave school and find work. I think that one of the hardest things to comprehend in fiction (and in real life!) is the line between what is under your control and what isn’t. Education is a great way to make a good life, but it isn’t the only way, and for many people, opportunity comes later. Kip accepts the limitations of his world and makes a good life for himself despite, or perhaps because, of his limitations. An admirable quality!

JF: Nine Days also underlines the impact of the war in the characters’ lives. It would be incredibly helpful to hear more about the social pressure Jack experienced before he enlisted in World War II (even though so many families suffered terrible losses in World War I) as well as the impact of rationing.

TJ: One of the many benefits that feminism has brought to the world is the idea that there’s no single way to be a man. In the middle of the last century, there wasn’t such a view. Valued masculine traits in Australia were bravery, strength, and being a good soldier. Even today, in parts of our media there’s an emphasis on Gallipoli as being the single most important event in our nation-building, and that there’s something unique and important in our Australian definition of ‘mateship’. The pressure on young men, from their friends, family and society in general, to conform to these norms was intense. There was also a strong view that England was ‘home’, even though most people had never been there. In the early stages of WWII, when Jack enlisted, Japan hadn’t yet entered the war, so the defence of England was considered more important than the defence of Australia.

And rationing lasted a long time and was intense! I wanted to include rationing in Nine Days because it’s one of those things that seems so, so strange to modern people. The government tells you how much you’re allowed to eat, and to buy, and everyone goes along with it? On the surface, it seems impossible to understand—but only ten to fifteen years ago, Victoria was in the grip of the tightest water restrictions in memory. Everyone bought egg timers for their showers and watered their gardens with buckets. I love this as a reminder that, if people are convinced that the reason is genuine and important, we can really band together and get things done.

JF: One of the things I love about Nine Days is the way it helps uncover the history of Melbourne, particularly Richmond. How different is Richmond today in comparison to the Westaways’ Richmond?

TJ: Richmond is a vital part of the story—I don’t think I could have set Nine Days anywhere else. Back in the Westaways’ time, Richmond was pretty much a slum. Very unhygienic and polluted, very poor. A great deal of social disadvantage. Now, of course, it’s gorgeous—full of trendy bars and cafes and lovely expensively renovated cottages. In this way, it’s metaphorical for the story I’m trying to tell, about this family. Over only four generations, the Westaways move from a very tenuous existence, with Jean in domestic service, to Stanzi being university-educated and Alec seeing no limitations on his future. This kind of movement over such a short span of time is really unprecedented in human history. It’s wonderful, I think, that we lead such different lives from our grandparents—but I don’t want us to forget where we’ve come from, or lose sight of the important things.

You can read the entirety of this fascinating interview here [PDF].

Nine Days is available as B format paperback and eBook from all good bookstores or via the Text website.

Toni Jordan’s latest novel is The Fragments, a superbly crafted and captivating literary mystery.