‘What a catch!’ From backyard games in the 1950s and an encounter at the historic Old Trafford game in ‘61 to Benaud’s heyday in the commentary box, Brian Matthews has traced the contours in the life of one of cricket’s greats.

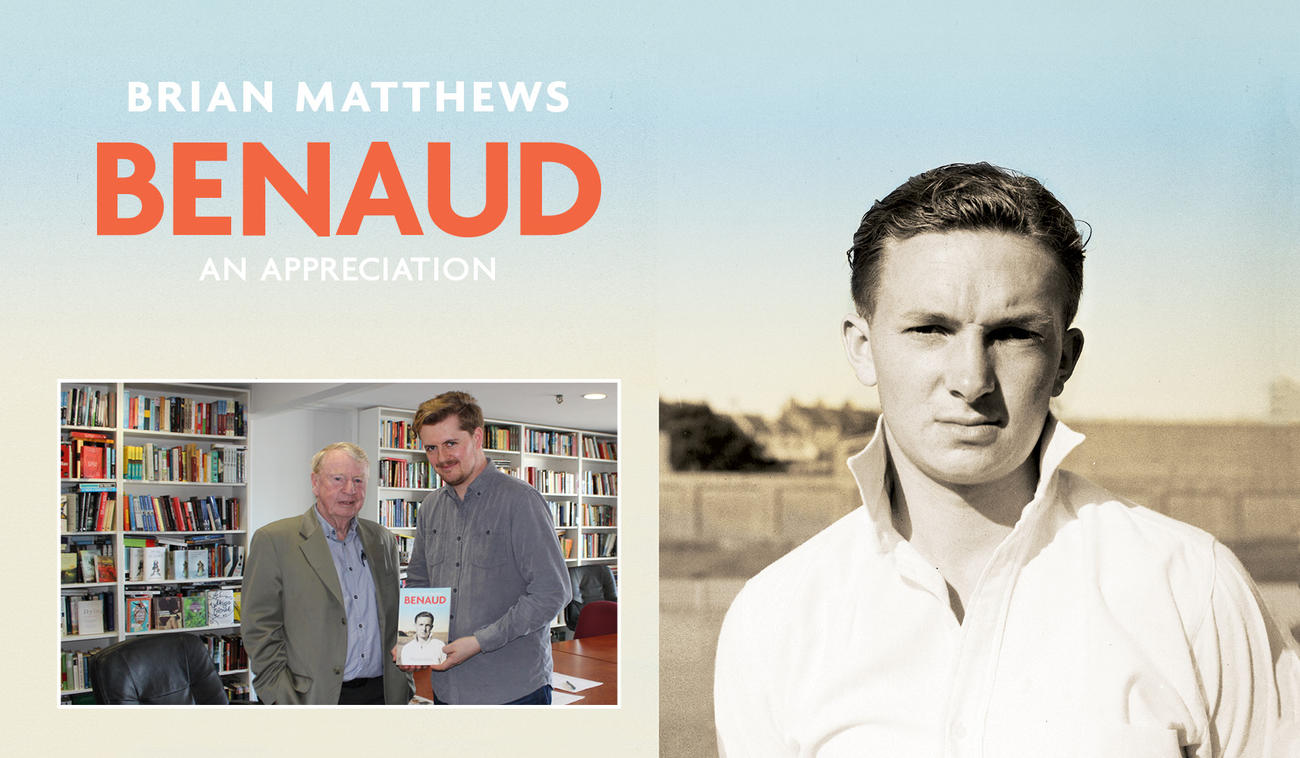

Text’s David Winter sits down with Brian to talk about his new book, Benaud: An Appreciation, and why Benaud is an irresistible subject.

Growing up, I saw Richie Benaud as a bastion of conservatism. A callow cricket fan, I couldn’t see beyond the beige suit. In the years since I’ve come to appreciate how Benaud was player of great flair, a renowned innovator and an advocate for change in cricket. These attributes come through strongly in your book: is this something you wanted to emphasise?

In writing the book I was conscious that Richie Benaud was not straitlaced and would sometimes oppose traditional views. We often expected him to caution the cricket world, but in fact he was positive about developments like Twenty20: he pointed out that batting, fielding and captaincy skills would change, would sharpen. He saw these things naturally, seemed to anticipate them. Unlike many—including me—who were against Twenty20, he saw its potential. Regarding the development of white and pink balls for use under lights he would say that if we could land a man on the moon we could probably develop a cricket ball that would be visible at night and perform in different conditions: it wasn’t rocket science, after all.

He was a quiet traditionalist as well, wasn’t he? He believed in the right behaviour, the right course of action? I’m thinking of the decades-long friend of Benaud’s quoted in the book who describes him at length to you—Benaud’s interest in the ‘good life’, his disdain for celebrity.

That was his personality, I think. He wasn’t old-fashioned but he was straight-down-the-line. For Benaud, cricket was a character-builder. His public reaction to the ‘underarm’ delivery was tough: it was the worst thing he’d seen on a cricket field, he said. His opinion wouldn’t budge over some things in cricket—the wrongness of the front-foot no-ball rule was one. But he could quickly spot the virtue of change in other areas. Razzmatazz was fine; different venues, new entertainment and so on—these could adapt over time. While he didn’t have much to do with the introduction of Twenty20, he was instrumental in the development of fifty-over cricket.

Do you think modesty was the key to his success as a commentator: knowing when to stay quiet? Or was it just one of a suite of good habits? He wasn’t so much a phrasemaker as he was drily funny, succinct, knowledgeable.

Modesty wasn’t the defining aspect of his commentary but it was certainly part of his success. As I describe in the book, in England in the 1960s he learned from the commentary masters: Maskell, Longhurst, O’Sullevan. All of them had a version of a pause—the moment of quiet before analysing what just happened. So that was taught. But it was also natural for him not to put himself beyond the boundaries of commentary.

The acclaimed sports writer Rob Steen couldn’t convince Richie Benaud that a biography was warranted. Benaud had written an autobiography of sorts, and that was that. Apart from Steen giving you his material, was there a moment when for you Benaud became an irresistible subject?

I followed his career avidly when I was young. Later I would go to the Adelaide Oval regularly to watch cricket. By that stage Benaud had stopped playing, but his presence in cricket was enormous. And then Shane Warne came along, and with him the interest in leg-spin, and I think that was the time I became especially interested in Benaud. Everyone around him closed ranks at the mention of a biography—by anyone. And once I saw Rob Steen’s papers I understood how strong that circle was. Why was Benaud so reticent? He wasn’t a reclusive person; he made himself available to people; but he was very private and he valued his privacy. The funny thing is that the refusal of an authorised biography often leads to unauthorised biographies…

A hat-trick of favourites: first, what’s your most admired sports book—leaving aside C. L. R. James’s cricket masterpiece Beyond a Boundary? Second, your defining Richie Benaud on-field performance? And, last, Benaud quote?

The Fight, by Norman Mailer, on the Rumble in the Jungle—I’ve returned to that many times over the years. It’s nearly perfect.

I watched Benaud in the Fourth Test of the Ashes at Old Trafford in 1961. On the last day he took six wickets. And his captaincy in near-freezing conditions: he cleverly requested a drinks break so he could talk with the whole team. He told them the match couldn’t be saved, and it would have to be won.

As for a quote, it has to be from Benaud’s commentary—probably one of those occasions when someone would take a blinder in the field, there’d be a roar from the crowd, a pause, and then that voice: ‘What a catch!’

Do you think Benaud would have applauded the Australian selectors’ decision to replace so much of the team for the recent Test in Adelaide, with an emphasis on youth and potential?

I imagine he would’ve appreciated the Test being played at night as well as in the day. The selections he might have seen as throwing the baby out with the bathwater, a bit over-the-top. But the situation was almost unprecedented in Australian cricket, and he might well have praised the bravery and innovation of the selectors.

And the commentary box—in your book you look at the effect of Benaud’s departure, how matiness was quickly to the fore. Will we see Benaud’s like again?

It was a radical, fast deterioration. But it has come back, to a noticeable extent, presumably in response to stern criticism. Mark Nicholas is very good at holding things together. Shane Warne and Michael Clarke offer great cricket insights. But there’s no one on the horizon who’s comparable to Richie Benaud. He picked his moment in England in the 1960s, learning from the finest commentators, then was in Australia in the 1970s for the Packer revolution and became the voice of cricket. No one matches his capacity for clear, eloquent, close observation.