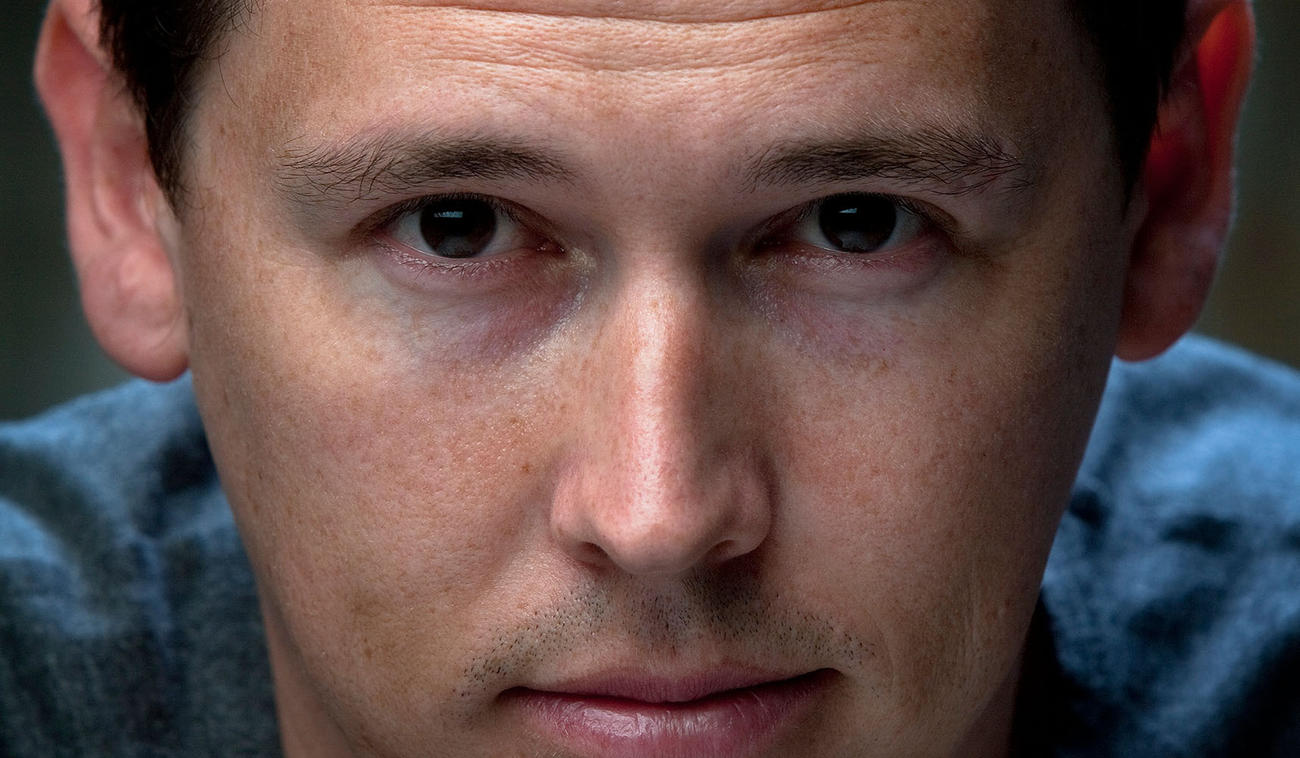

Zane Lovitt was a documentary filmmaker before turning his hand to crime fiction. His debut novel, The Midnight Promise, won the Ned Kelly Award for Best First Fiction, and led to Zane being named one of the Best Young Novelists of 2013 by the Sydney Morning Herald. His writing was compared to the likes of Raymond Carver, Quentin Tarantino and Peter Temple, to name a few.

Zane’s much anticipated new novel, Black Teeth, is released next Monday, 27 June. He spoke to us about the pleasures and frustrations of writing crime fiction in the Lucky Country.

What makes great crime writing?

Probably, there’s two kinds of good crime writing. The first is the cream of the sausage-factory stuff that fills the shelves in the Crime Fiction section. An effective potboiler is good if it asks a question at the start that the reader wants answered. Often this question is whodunit? but it can be a how or a why or something else. If the book can hook the reader with a question like this, then even a fickle bastard like me will read to the end, just to find out the answer.

The second kind does the same thing, but is trying to produce more than mere escapism. To Kill a Mockingbird is a courtroom drama, whatever else you’d say about it as a literary achievement. The Name of the Rose is a murder-mystery. They’ve got all the tropes of the genre, but there’s more going on. That’s the great stuff, IMHO. Though it may not come along very often.

There might be a third kind of great crime fiction, which is the kind of book that belongs to the first, sausage-factory category, but which does something really interesting with the voice/style of writing. This is where the Chandlers and Hammetts belong. Chandler famously railed against contrivance, but he was as guilty as anyone of indulging it. It’s the voice of Philip Marlowe that he’s remembered for.

How does your previous work as a scriptwriter inform your writing?

I only ever studied screenwriting; I can’t claim to have ever worked as a screenwriter. What I learned is all the stuff that movies do so well: visual characterisation, plot-based stories, the climactic decision as the story’s raison d’etre. If I want a rollercoaster of a yarn, I turn to the movies. What I didn’t learn is the stuff that prose fiction is so good for: deep detail and a unique voice. This is what I want when I read a book. Though, as per above, my favourite books do it all.

Your earlier book, The Midnight Promise, was written as a series of interlinking vignettes while Black Teeth follows the more straightforward structure of a novel. How did your writing process differ for these two books?

It didn’t really differ. It still demanded the same measures of frustration, poverty and caffeine. It still took me way too long to write. I like to have the whole story clear in my mind before I start to write it, and that’s a lot easier with a short story than with a novel. But with a novel, you only have to do it once, so I suppose it balances out.

Jason is paid to scrutinise prospective job candidates on behalf of their employers, which doesn’t seem to win him many friends. Why did you want to explore these issues of privacy and online surveillance?

Privacy has become synonymous with anonymity, thanks to the emergence of the online world. For a book that is questioning when and how humans feel loyalty, I had to admit that, in the anonymous world of image boards and trolling, loyalty still exists, but it is stratified and fucking labored over. Whereas, in high-security male prisons (one of which we glimpse in the book), there is no anonymity, everything you do and say is in the context of your identity. You can’t escape it. And in prison, loyalty is everything. The anonymous online world, despite still being intensely male, is the exact opposite.

Beyond the lively characters, Black Teeth is also written with a very dry and very dark sense of humour. Was it difficult to find this comedy from within the grit and grime of a crime novel or did it come quite naturally?

Naturally. That’s just me. I would have trouble not writing like that.

Why do you think noir writing is so poorly represented in Australian fiction?

It’s the price we pay for living in the Lucky Country, right? Our tap water is drinkable, our race relations are placid, our gun laws are strict, our Federation was formed without its stakeholders all killing each other. Australian streets are some of the safest in the world. So our crime stories have to work a little bit harder. When a writer relies on hoary old hit men and drug cartels, it’s probably not going to ring true in an Australian context.